The production of medicines at a rate that meets demand remains a major challenge for the pharmaceutical industry — and 3D printing could be the solution.

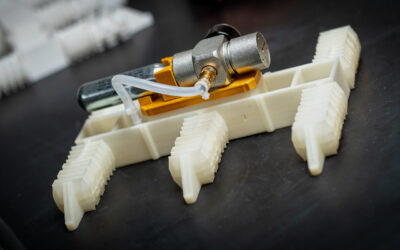

Alvaro Goyanes and his team at University College London are experimenting with a 3D printing manufacturing method, and have reduced the amount of time needed to produce certain medicines from three to four minutes down to several seconds. Goyanes predicts they can eventually cut this done to one second.

The method employed the team is called vat photopolymerisation, which involves printing an entire tablet at once. In contrast, other printing approaches produce tablet components separately.

The technique involves a laser that makes contact with a solution and turns it into a solid. “Normally, this creates the object layer by layer, but in vat polymerisation, you have three beams which come from three different sides,” explained Goyanes. “When the three beams of light touch, the resin goes from liquid to solid.” Furthermore, using a mirror system, it is possible to create complex structures.

Goyanes says the printers that his team has developed cost roughly the same as the equipment used by the pharmaceutical industry, meaning that cost should not be a deterrent for implementing the technology.

Beyond an increased rate of production, another advantage of 3D printing is its potential to produce tailored medicines, which could carry great health benefits for patients. “Up to 70% of medicines currently given to patients are not as effective as they could be, in large part due to the sub-optimal doses given,” said Goyanes. “If dosage is too high, patients may suffer unpleasant side effects, whereas dosage that is too low might not generate the desired health benefit.”

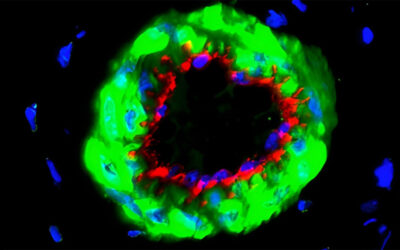

Compared to batch production, 3D-printed medicines can be tailored by concentration and release method. Adriane Maxime, a pharmacist at the Gustave Roussey Institute, the largest cancer clinic in Europe, explained: “3D printed medicines could allow for the development of medicine that is slow release, fast release or a mixture of both. This would allow the dose to be released into the bloodstream at customizable rates.”

The team has already successfully completed a proof-of-concept creation of the blood-thinning drug warfarin in a way that allows for doses to be released at a tunable rate.

“The potential for using 3D printing to make medicines is even more exciting though,” said Maxime. “Using 3D printing, it might also be possible to create medication that contains multiple medicines in a single tablet.” This would be particularly useful for over-65s, nearly half of whom take multiple medications.

The pharmaceutical industry has recognized the potential of 3D printing, which is why medicines produced by the method have begun clinical trials. Goyanes estimates that in a best-case scenario, “we could begin to see 3D printed medicine used in the health service within three to five years”.

Clinical trials are currently underway at Gustave Roussy Institute, Paris and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London. Researchers at the institutions are testing how effective 3D-printed medicine is at treating conditions from the rare Fragile X Syndrome to cancer. They plan to soon begin a year-long trial involving over 300 breast cancer patients who will be provided with 3D-printed medication of a tailored dosage to test if it leads to a reduction in the drug’s unwanted side effects compared to a control group.

If these trials are successful, the use of 3D-printing could well lead to what can justifiably be labelled as a revolution in the production of medicines. Not only will medicines be produced at a much faster rate, helping to reduce their prices, but also tailored so as to generate improved health outcomes.

Reference: Lucía Rodríguez-Pomboa, et al., Volumetric 3D printing for rapid production of medicines, Additive Manufacturing (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.addma.2022.102673