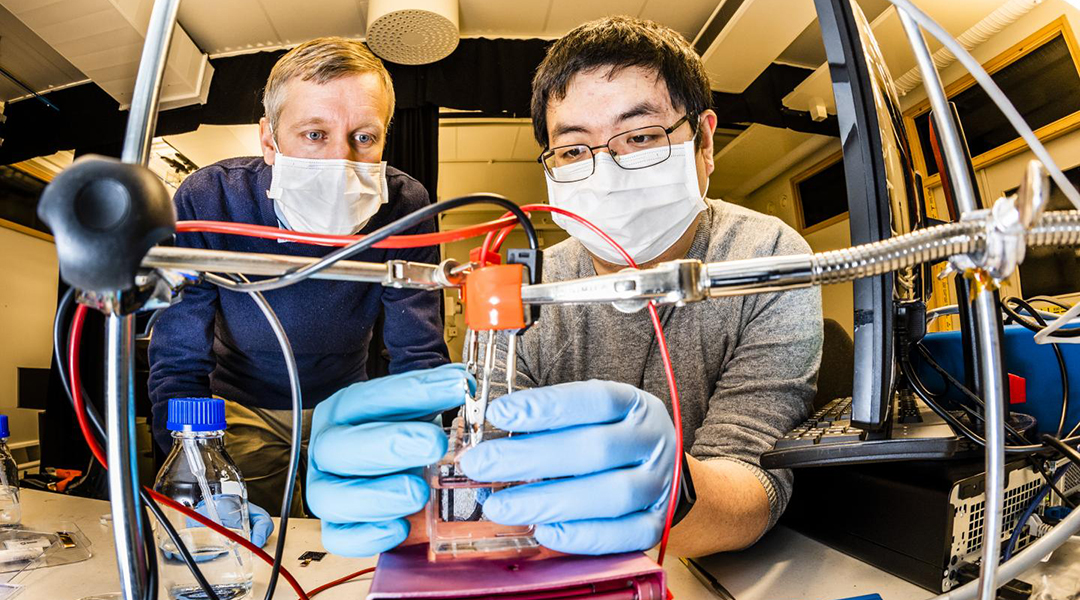

Image credit: Thor Balkhed

We usually think of colors as created by pigments, which absorb light at certain wavelengths such that we perceive color from other wavelengths that are scattered and reach our eyes. That’s why leaves, for example, are green and tomatoes red. But colors can be created in other ways, and some materials appear colored due to their structure.

Structural colors can arise when light is internally reflected inside the material on a scale of nanometres. This is usually referred to as interference effects. An example found in nature are peacock feathers, which are fundamentally brown but acquire their characteristic blue-green sheen from small structural features.

Researchers at Linköping University have developed a new and simple method to create structural colors for use in reflective color displays. The new method may enable manufacturing of thin and lightweight displays with high energy-efficiency for a broad range of applications.

Reflective color displays differ from the color displays we see in everyday life on devices such as mobile phones and computers. The latter consist of small light-emitting diodes of red, green and blue positioned close to each other such that they together create white light. The color of each light-emitting diode depends on the molecules from which it is built, or in other words, its pigment. However, it is relatively expensive to manufacture light-emitting diodes, and the global use of emissive displays consumes a lot of energy.

Another type of display, reflective displays, is therefore being explored for purposes such as tablet computers used as e-readers, and electronic labels. Reflective displays form images by controlling how incident light from the surroundings is reflected, which means that they do not need their own source of illumination. However, most reflective displays are intrinsically monochrome, and attempts to create colour versions have been rather complicated and have sometimes given poor results.

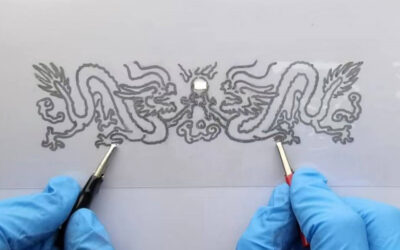

“We have developed a simple method to produce structural color images with electrically conducting plastics, or conducting polymers. The polymer is applied at nanoscale thicknesses onto a mirror by a technique known as vapor phase polymerisation, after the substrate has been illuminated with UV light. The stronger the UV illumination, the thicker the polymer film, and this allows us to control the structural colours that appear at different locations on the substrate,” said Shangzhi Chen, one of the study’s authors.

The method can produce all colours in the visible spectrum. Furthermore, the colours can be subsequently adjusted using electrochemical variation of the redox state of the polymer. This function has been popular for monochrome reflective displays, and the new study shows that the same materials can provide dynamic images in colour using optical interference effects combined with spatial control of nanoscale thicknesses.

Magnus Jonsson, associate professor at the Laboratory of Organic Electronics at Linköping University, believes that the method has great potential, for example, for applications such as electronic labels in colour. Further research may also allow more advanced displays to be manufactured.

“We receive increasing amounts of information via digital displays, and if we can contribute to more people gaining access to information through cheap and energy-efficient displays, that would be a major benefit. But much research remains to be done, and new projects are already under way,” said Magnus Jonsson.

Reference: Shangzhi Chen, et al., Tunable Structural Color Images by UV-Patterned Conducting Polymer Nanofilms on Metal Surfaces, Advanced Materials (2021). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202102451