Like all the best science stories, the field of adjuvant science began when a researcher noticed something odd. Back in the 1920s, Gaston Ramon’s job was to inject horses with tetanus and extract the plasma for use in vaccines. He noticed that the concentration of antibodies in the plasma was higher for horses who had a strong reaction at the initial injection site.

Ramon inferred that this reaction aided the immune response, and various scientists around the world started experimenting with the deliberate addition of chemicals to their vaccines that might provoke such a response. Ramon tried (among other things) starch, breadcrumbs, and tapioca, but the first adjuvant to be approved for administration to humans were the aluminium salts developed by Alexander Glenny.

This material stood as the only approved adjuvant in vaccines for 70 years. The mechanism of action is still not completely worked out, but the general principles involved are well agreed upon. The aluminium salts provoke an innate inflammation response, which is thought to prime the adaptive immune response for action, leading to more effective production of antibodies for fighting specific antigens.

Since the mid 90s, seven more adjuvants have been approved for use in vaccines, and two of the most high profile COVID-19 vaccines rely on their use (the Norovax and Sanofi/GSK candidates). The new adjuvants provoke different immune responses that are designed to provoke strong antibody responses. A total of eight possible adjuvants is a stunningly small number in a field as crucial as vaccine development. In that context, a great deal of work is being done worldwide on the development of new adjuvants.

Part of the difficulty with adjuvant research is the sheer complexity of the immune system. For an adjuvant to be effective it must provoke an innate immune response strong enough to kick start an adaptive immune response, but not so strong that secondary effects become an issue. In a set-up with as many moving parts as our immune system, striking this balance is no mean feat.

An American team have recently reported the development of an experimental adjuvant made from lactic acid and choline (giving it the portmanteau of ChoLa), two chemicals that are made by the body.

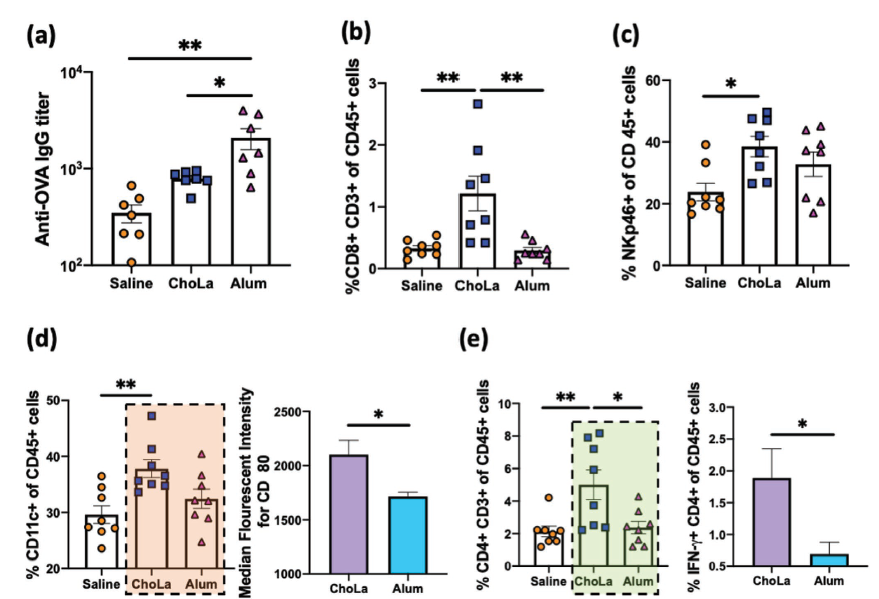

The team showed that injecting a 10% solution of ChoLa into mice did not induce any serious adverse side effects. Next they combined the adjuvant with a model antigen and the two were injected into mice. The immune response of this group was then compared with both that of a group of mice who were injected with the same antigen and a traditional aluminium salt (alum) antigen, and a group who were simply injected with saline.

To illustrate the complexity of the systems that need to be monitored to assess the success of an adjuvant, the figure from the paper showing the response of various actors in the immune system to the three conditions is presented below.

The take-home message from this figure is that some elements of the immune system showed a stronger response to the ChoLa adjuvant than the aluminium salt adjuvant: However mice treated with the older adjuvant showed a higher titer of antibodies to the model antigen than those treated with ChoLa.

The authors argue that given the ease of manufacturing and safety profile of ChoLa, it deserves further consideration as a candidate for expanded trials. They would also like to see how the system works when multiple antigens are used instead of just one.

This work demonstrates the development of a novel adjuvant which has an acceptable safety profile, which is no mean feat, and may one day serve as an addition to our vanishingly small repertoire.

Reference: A. Ukidve et. al. Ionic‐Liquid‐Based Safe Adjuvants, Advanced Materials (2020) DOI: 10.1002/adma.202002990