In Sub-Saharan Africa, mostly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, people are still suffering from sleeping sickness or Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT). This disease, caused by a parasite, is transmitted through tsetse fly bites, and if untreated, can be fatal.

A recent study treating sleeping sickness highlights the battle we still face with this neglected tropical disease. This research, published in the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases, evaluates a single dose of a new drug called Acoziborole, and gives hope that this easy-to-administer treatment could achieve the goal set by WHO of interrupting transmission by 2030.

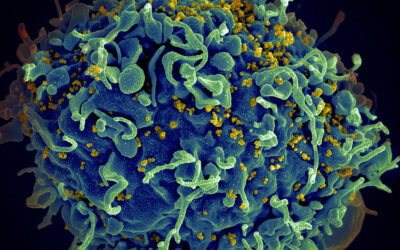

In early stages of the disease, the parasites remain in the blood, lymphatic system, and tissues, causing symptoms such as fever and headaches. When left untreated, they cross over the blood-brain barrier, triggering neurological problems and late-stage disease.

Current treatments depend on disease stage because drugs used to treat late-stage disease need to cross the blood-brain barrier, where early stage therapies do not. Nifurtimox–eflornithine combination therapy (NECT) has long been used for late-stage disease but requires hospitalization in order to be administered intravenously. Another, Fexinidazole, was introduced in 2019 and is an oral, once-a-day, 10 day treatment for both stages of the disease; however, it needs to be administered with food, under supervision of trained staff, and requires hospitalization.

The problem is that while these therapies are effective in treating patients, the disease is prevalent in remote areas with few hospitals, clinics, and resources, making treatment and diagnosis challenging.

Antoine Tarral, medical lead at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), and his collaborators aim to address this unmet, clinical need for this neglected disease. “A single oral dose of acoziborole is a clear improvement compared with 10 days of NECT since disease staging by painful lumbar puncture and hospital admission for intravenous treatment are not required, and the treatment duration is shorter,” wrote the scientists in the paper.

Their study, conducted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Guinea, measured the success rate (cured or likely to be cured) of using a single dose of Acoziborole to treat both stages of disease 18 months after treatment.

Accessible medicine in low-resource settings

A major advantage is that this drug is taken orally, removing the need for intravenous drug administration that current therapies like NCET require. Importantly, Acoziborole was found to be safe with only mild to moderate drug related reactions reported. It was effective in treating both early and late-stage disease, demonstrating good success rates and comparable efficacy to the standard NECT based on historic data.

“Based on these findings, the benefit–risk profile of acoziborole for adults and adolescents with gambiense HAT, regardless of disease stage, is considered positive,” wrote the researchers.

Additionally, the team argued that patient management is easier because a lumbar puncture to diagnose disease stage and hospitalization to give the drug would no longer be needed. Furthermore, the shipping logistics of the drug are easier, also an important consideration in low resource settings.

In a subsequent “Comment” article published in the same journal, Jacques Pépin, an independent researcher acknowledged the study was small and without a control group. However, he wrote, “But these were difficult challenges to overcome, considering the drastic reduction in the number of patients with HAT and dispersion over a vast territory, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. For these reasons, the authors took a pragmatic approach instead.”

At the time of writing, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, another study that includes a control group is ongoing to further test the drug’s safety.

The end of the road for sleeping sickness?

With the number of cases decreasing, Pepin says an interruption to transmission is close. Could Acoziborole be the last piece of the puzzle that revolutionises treatment and finally interrupts transmission?

When we are this close, the road ahead is not easy, and Pepin warns of further challenges, including the potential threat of animals harboring the parasite. With that said, the findings from this recent study brings us a step closer to an accessible drug that reaches those most in need to treat a neglected but serious disease.

Reference: Antoine Tarral, et al., Efficacy and safety of acoziborole in patients with human African trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2/3 trial, Lancet Infect Dis (2022). DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00660-0

Edits made January 3, 2023 to add additional information about Fexinidazole and to correct the professional title of Antoine Tarral.