It is not unusual that scientific discoveries happen when someone accidentally finds something they aren’t really looking for. In the history of science, there exist dozens of examples of truly unexpected and exceptional discoveries that have changed the course of science and have revolutionised our daily lives. Radioactivity, penicillin, the microwave, and X-rays are just a few of the most well-known examples of these “lucky accidents” discovered by chance. But as Louis Pasteur said, “Chance favors only the prepared mind.”

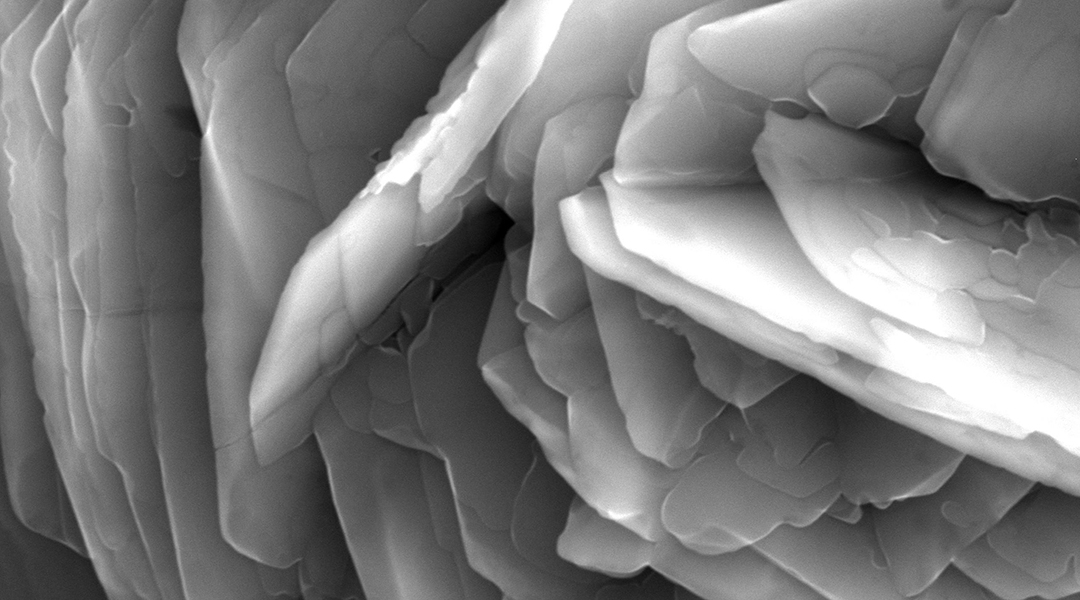

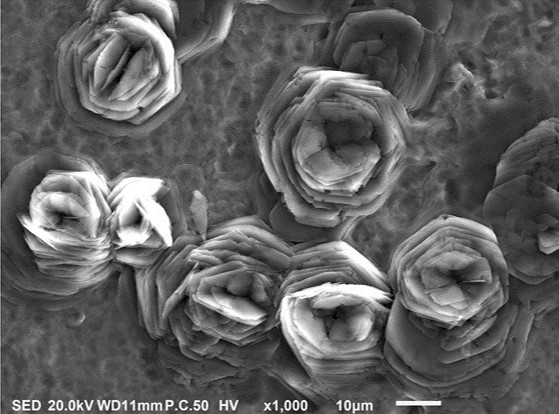

While carrying out research to optimize multiscale surface roughness for implantology applications, a team of researchers from Liberty University (LU), Lynchburg, Virginia, USA, led by Dr. Hector Medina unexpectedly discovered a new surface formation on titanium specimens. This previously unobserved structure consists of rosette-like formations with “petals” that possess thickness in the nanosize scale (Figure 1).

The discovery was made via scanning electron microscopy of titanium specimens that had undergone etching using sulfuric acid at temperatures between 60 to 90 °C. Dr Medina’s team was firstly amazed when they saw the micrographs presented by Rachel Kohler, who back then was a mechanical engineering student at LU (now a graduate student at Purdue University). “I thought I was looking at a black-and-white picture of a garden,” said Dr. Medina.

Whilst the practical implications and further understanding of this discovery are to be explored and will be the subject of future studies, the first preliminary results, which have recently been published in Engineering Reports, may have implications in corrosion science, manufacturing of titanium-based implants, and in the science of fluid-surface interactions.

The novel formations exhibit physical characteristics that resemble flowers. Not only does this make them aesthetically fascinating, but it also represents an ideal feature for applications in certain processes where chemical reactions in fluids are assisted by surface chemistry, and enhanced by surface roughness.

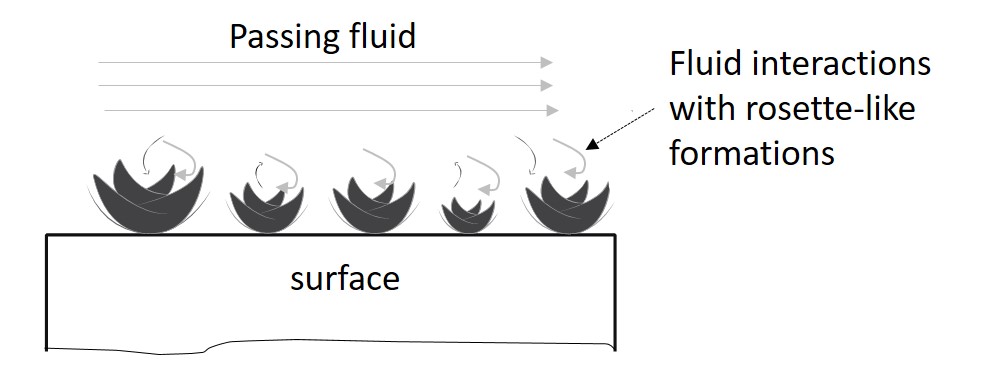

It is known that the structure (and composition) of a surface can indeed strongly influence the fluids passing by (Figure 2).

This type of interaction is crucial in applications such as selective catalyst reduction or water purification processes (e.g. removal of lead). Besides the chemical makeup of the surface, the key factor is that enhanced roughened surfaces can provide more area for reactions and serve as small “static mixers.” The tiny petals seen in these novel formations have hence the potential to improve local mixing and enhance chemical reactions. Other flower-like formations have been observed in the past, which have proven to be applicable in some of the aforementioned fields.

As part of current and future work, Medina’s team is currently investing the crystallographic character of the nanopetals. The understanding of the thermal-chemical potential, activation energies, and other parameters involved in the formation of these structures is also underway, though its execution has been impacted by the current COVID-19 pandemic.

The team is confident that this rosy and tantalizing discovery will open equally fascinating opportunities, and hope their findings will spark interest, debate, and collaborations within the research community.

Reference: Hector Medina, Rachel Kohler, ‘Novel rosette-like formations with nanothick petals observed on acid-etched titanium‘ Engineering Reports. (2020) DOI: 10.1002/eng2.12247