Complications following abdominal surgeries from “leaks” can be life-threatening if detected too late. A small plastic strip developed by researchers at the ETH Zurich and Empa offers a simple solution to detect leaks in the gastrointestinal tract as soon as they occur without requiring trained hospital staff or additional laboratory equipment.

In a recent study published in Advanced Science, Inge Herrmann and her team at the Nanoparticle Systems Engineering Laboratory harnessed the power of enzymes normally found in the gastrointestinal tract, attaching them to a test strip that can be used easily detect tissues that haven’t healed and have started to leak.

“The leaking of non-sterile, digestive fluid in the GI tract can lead to serious intra-abdominal infections and septic shock. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the outcome,” said David Clark, professor of surgery at the University of Queensland and senior visiting colorectal surgeon at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital in Australia, who was not involved in the study. “Real time testing with a visual indicator would be a substantial advance, and this is the first such report of this technique.”

Digestive enzymes as indicators

During the post-surgery healing process, the body produces wound fluid that is typically collected in surgical drains fed by tubes connected to the surgical site at the patient’s bedside. To monitor complications, the fluid is regularly sampled and tested in laboratories for the presence of intestinal contents or microbes that would be indicative of infection.

These tests, though precise, are time-consuming and require trained personnel and equipment that are not always available. They also represent one point in time, typically a morning specimen, and are tested only once a day.

“Detecting [leaks] is challenging for two main reasons: clinical symptoms often manifest late, typically after sepsis has set in, and the current methods of detection involves monitoring intervals of up to 48 hours during which patients are not observed,” said Alexander Jessernig, a doctoral student in Herrmann’s lab and lead author of the study.

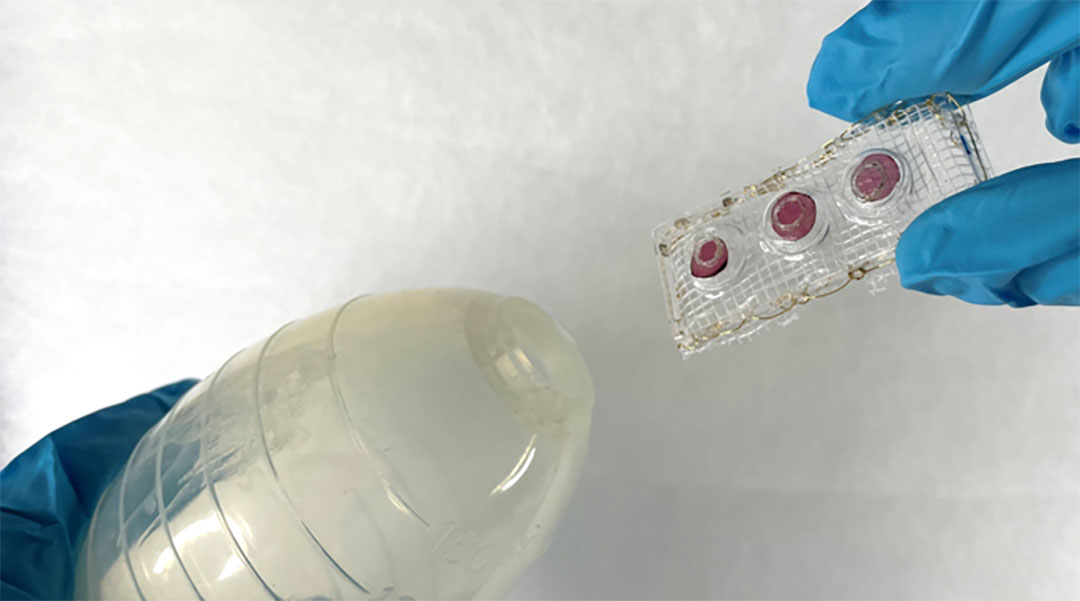

To address these issues, Herrmann’s team developed SensAL, a thumb-sized device that can be placed into surgical drains that changes color as soon as a leak occurs. It contains three gel-like spots placed on a plastic strip that contain either gelatin, starch, or coconut fat. Incorporated into these gels are different colorants, giving each spot a unique appearance.

“When a leak occurs, enzymes accumulate in the drain and come into contact with the [gels],” explained Herrmann. “Over the course of a few hours, the enzymes digest the [gel components], releasing the colorant and causing the [gel spots] to change color or disappear.”

Putting SensAL to the test

In test fluids containing various enzyme concentrations, SensAL proved highly sensitive, detecting even minor leaks in less than 12 hours. When tested in real-life scenarios with 32 samples of drain effluents from patients who had undergone abdominal surgery, SensAL accurately identified all cases in which leaks had occurred.

“Enzymes are catalysts, meaning they continue to cleave bonds in the hydrogel until all are destroyed,” said Herrmann. “Therefore, even a small amount of enzyme can generate a large signal, and signal to medical staff that the patient may have a [gastrointestinal leak].”

The team is now refining SensAL with a larger set of patient samples to determine the average detection time and identify which types of surgeries would benefit most from this approach.

“The main limitations center around the position of the drain in relation to the [surgical site],” noted Clark. “Malpositioned surgical drains may be falsely reassuring.”

Another challenge is that the surgical site itself is not always rich in enzymes, which may lead to weak signals, even when there is leaking. These issues are inherent to post-surgery patient monitoring and are not related to the SensAL device itself, but they do require careful interpretation of the results, cautioned Clark.

Despite these challenges, Herrmann remains optimistic. “It may be a few years before SensAL is available in hospitals worldwide, but we are working tirelessly to make this vision a reality.”

Reference: Alexander Jessernig, et al., Early Detection and Monitoring of Anastomotic Leaks via Naked Eye-Readable, Non-Electronic Macromolecular Network Sensors, Advanced Science (2024). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202400673