Fiona Smaill and research coordinator Emilio Aguirre demonstrate the use of the nebulizer with a volunteer. Photographer: Georgia Kirkos

A team of scientists from McMaster University, Canada have announced that two new inhalable COVID-19 vaccines have been approved for human clinical trials beginning in 2022. The vaccines will be administered as boosters, given to healthy individuals who had previously received two doses of an approved COVID-19 vaccine.

Inhalable nasal spray vaccines have been gaining momentum, especially in the last year, with greater potential to break infectious chains by providing a more accessible means of protection to individuals. The idea is to halt infection at the body’s point of entry, where SARS-CoV-2 viral particles infect cells in the nose before progressing to the lungs and other organs.

Where current vaccines, including Pfizer, Moderna, and J&J, all incorporate elements of the virus’ spike protein to stimulate an immune response against SARS-CoV-2, the new vaccines include two additional proteins in addition to the spike protein.

“This is the first time that a vaccine has been developed containing three […] important proteins of the COVID virus, and so our belief is that this will broaden the immune response and lead to better protective immunity,” said infectious disease specialist and professor of pathology and molecular medicine at McMaster University, Fiona Smaill.

The downside to targeting the spike protein, as we’re seeing with new and emerging variants of concern, is that it is very likely to mutate, making it trickier for our immune systems to recognize it. “That’s what the concern is about the existing vaccines — that they target only the original spike and may be waning in effect,” said Smaill.

By incorporating two SARS-CoV-2 proteins from regions in the genome that remain conserved through each new variant, the team hopes their booster will remain effective in an ever-changing viral landscape. “By targeting a breadth of immune responses to different parts of the COVID virus, we expect to see broader protection,” she added.

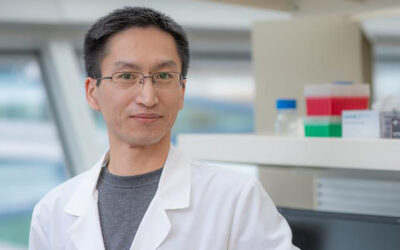

The vaccine delivery platform was modelled off a tuberculosis vaccine that Smaill’s co-investigator, Zhou Xing, professor of medicine at McMaster, has been researching and developing for over two decades.

“Our [vaccines get] delivered into the lung via inhaled aerosol to induce respiratory mucosal immunity, known to provide best protection against respiratory pathogens,” explained Xing.

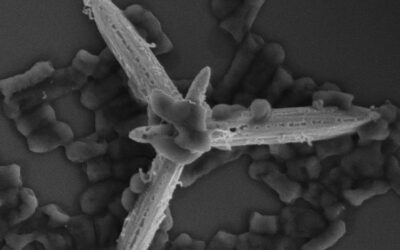

The new vaccines are adenovirus vectors, platforms commonly used for flu vaccines as well as AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine.

“In their natural form, adenoviruses cause respiratory infections such as the common cold, and in rare cases can cause a lung infection such as pneumonia,” wrote the team in a press release. “In their weakened form, they do not spread disease, but can be customized to serve as vehicles, or vectors, to trigger targeted immune responses.”

At least 30 healthy volunteers have been recruited for this first phase of the study, which is expected to run for four to six months. During this time, the team will be investigating how the body’s immune response develops in both the lungs and the blood after inhaled inoculation, as well as monitoring for possible adverse reactions and side effects.

If successful, sufficient vaccine doses have been produced to move forward with much larger clinical trials.

“This human trial builds on pioneering work, and in addition to addressing an issue of tremendous public health importance, will also advance our fundamental understanding of how to use these viruses most effectively as vaccine vectors,” said Matthew Miller, an associate professor with McMaster’s Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research and co-principal investigator, in a statement.