For over three millennia, ancient Egyptians mummified the bodies of deceased people and animals in order to facilitate their passage into the afterlife. Such was their skill at preserving the bodies that some of those mummies have lasted until today — although exactly how they achieved this is still quite a mystery.

A new study unveils some of the key substances used and concludes that Egyptians had a refined knowledge of their chemical properties. What’s more, the geographically distant origin of some of the substances possibly uncover the first global trade networks in human history.

A unique opportunity

It all started with the discovery of the first-ever known embalming workshop dating from the 7th-6th centuries BC in Saqqara, located about 30 kilometers south of Cairo along the river Nile. In 2016, the late Ramadan Hussein, a linguist and archaeologist who was professor of egyptology at the University of Tübingen, stumbled upon over one hundred ceramic vessels, some of which had inscriptions about mummification practices.

Hussein saw a unique opportunity to piece together a much bigger picture of the mummification process than had ever been drafted and gathered a very diverse team of specialists in fields ranging from anthropology to botanical residues and several Egyptian languages.

One member was biomolecular archaeologist Maxime Rageot, a colleague of Hussein’s at Tübingen University who became the lead author of the paper. “Embalming workshops are quite rare,” he said. Indeed, up to now, egyptologists have pieced together their knowledge about mummification practices from papyri, some limited archaeological research, and analyses of individual mummies. But having access to labeled vessels would provide valuable insight about a larger part of society.

The researchers selected 31 vessels with inscriptions and decided to examine them from both a linguistic and a chemical perspective. They obtained small samples from the inner surface of the vessels in order to capture the organic substances it would have been in contact with, taking care to discard the topmost layer in order to avoid contamination from the passage of time, and took them to a chemistry lab at the National Research Centre in Cairo.

A myriad of substances

Advanced chemical techniques allowed them to identify a myriad of substances: various resins — including some from Pistacia trees and one called elemi — some animal fat, beeswax, bitumen, and an oil or tar of juniper, cypress, and cedar.

In parallel, they deciphered the hieroglyphs and Demotic inscriptions on the vessels and found mostly instructions such as “to put on his head”, “to make his odor pleasant”, or “to wash”. That is how they deduced, for example, that elemi and juniper or cypress oil would have been used for embalming the head.

Some of the vessels did contain words referring to their contents, and the team’s analysis revealed that they might have been wrongly translated — at least some of the time. For example, while “antiu” is usually associated with myrrh or frankincense, at Saqqara it referred to juniper, cypress, and cedar oil mixed with animal fat. “It’s interesting,” Rageot said, “because […] in all the vessels with this word [there was] the same mixture”.

Thanks to this work, “we are beginning to understand the common ingredients […] as well as the long history of embalming practice,” said Carl Heron, director of scientific research at the British Museum who was not involved in the paper.

Embalming chemists

The choice of these ingredients is far from coincidental, the study argues. They all have antibacterial, antifungal and odoriferous properties that were “perfect for mummification,” said Rageot, as they preserve tissues and reduce the smell of putrefaction. Plus, they’re hydrophobic and adhesive, so they can seal the skin and make sure line wrappings stay stuck to the body.

The new research “shows [ancient Egyptians] were aware of that,” said Rageot. “They were kind of embalming chemists.”

Now, the researchers plan to analyze the mummies at Saqqara to understand whether embalming practices differed by gender, age, or other features. Next, they aim to compare their results with findings from other workshops later in history.

But perhaps the most surprising discovery of all is the fact that some of these substances must have come from very distant locations — as far as the tropical rainforests of Africa or South East Asia. While it was already known that ancient Egyptians traded with other parts of the Mediterranean, there was no previous evidence to show that their network expanded to such distant continents. “It shows sort of the first globalization,” said Rageot.

The bitumen they found came from the Dead Sea, even if there was bitumen in Egypt too. According to Rageot, this shows the embalmers went out of their way to find this specific type of bitumen, possibly for some specific properties it might have had.

Tracing the origin of these substances more precisely as well as the exact trade routes the Egyptians would have followed, as the researchers plan to do, will provide key insights well beyond mummification practices and give a broader picture of what the world as a whole looked like in the 7th-6th centuries BC.

Reference: Maxime Rageot et al., Biomolecular analyses enable new insights into ancient Egyptian embalming, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05663-4

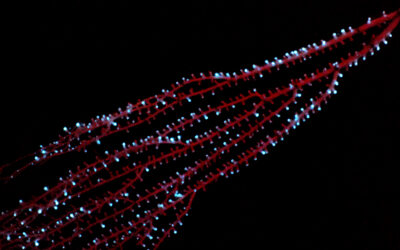

Feature image: Vessels from the embalming workshop. Credit: © Saqqara Saite Tombs Project, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. Photographer: M. Abdelghaffar