A group of scientists from Australia and the US have studied in detail the genetic sequences of immune cells, looking for specific markers in their DNA called genomic fingerprints that could help explain the development of different autoimmune diseases and inform therapies to treat them.

“We created a library of over one million cells from 1000 individuals,” said Joseph Powell, professor at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, Australia and director of the Garvan-Weizmann Centre for Cellular Genomics, and co-lead author of the study. “We did this using single-cell sequencing, a new technology that allows us to detect subtle changes in the RNA profile of individual cells.”

The study included an analysis of genetic markers associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and ankylosing spondylitis.

A library of genetic markers for better clinical outcomes

The immune system defends us against infection by foreign pathogens, but sometimes a malfunction can lead to the development of an autoimmune disease — a condition in which the body’s immune system mistakes its own healthy tissues as foreign and attacks them.

“There are more than 80 autoimmune diseases, and type 1 diabetes is one of them,” said Powell. “If we look at the most recent governmental statistics, 7 Australians are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes every day.”

The challenge in this field of medicine is the substantial variation between individual immune systems, which can result in different outcomes when the same drug is used to treat a disease in different people. “Unfortunately, there is no cure for any autoimmune disease,” said Powell. “Currently, patients are offered drugs either to relieve their symptoms or slow the progression of the disease. Often these drugs are not disease-specific and not effective in all patients. So, a patient may be prescribed a medication that will not necessarily work for them and may need to change over time.”

In light of this unmet need, the scientists created their library of genetic markers and associated each marker with a probability of developing a specific autoimmune disease. Knowing which cell types are involved in the development of a specific disease could then be used to better define a treatment course.

“The catalogue we generated will help design disease-specific drugs and tailor treatments based on patients’ DNA information,” said Powell. “In future, a patient with an autoimmune disease can go to their doctor, give a blood sample and get their DNA tested. Then we will be able to find matching drug treatments according to their needs.”

Someday, this study may even help prevent the development of autoimmune diseases. “We are sure that utilizing this library we generated, it is possible to find new biological insights into disease prevention,” added Powell.

Beyond just autoimmune diseases

The extent of this study is not restrained to autoimmune diseases — cancer patients will also benefit. After performing a similar study for cancer, patients could find an appropriate course of therapy that could help minimize unnecessary side effects often associated with chemo- or radiation therapies.

“This study generated a library of genetic markers for various immune cells,” said Powell. “When we complete the same analysis in cancer patients, we can compare the libraries for each immune cell between two groups and identify those differences.

“We have made this data available to other researchers as it is often not possible for others to access samples from a large number of patients,” added Powell. “To this end, this resource we generated will pave the way for new drug development and repurposing of currently available drug treatments for autoimmune diseases.”

Reference: Seyhan Yazar, et al, Single-cell eQTL mapping identifies cell type–specific genetic control of autoimmune disease, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abf3041

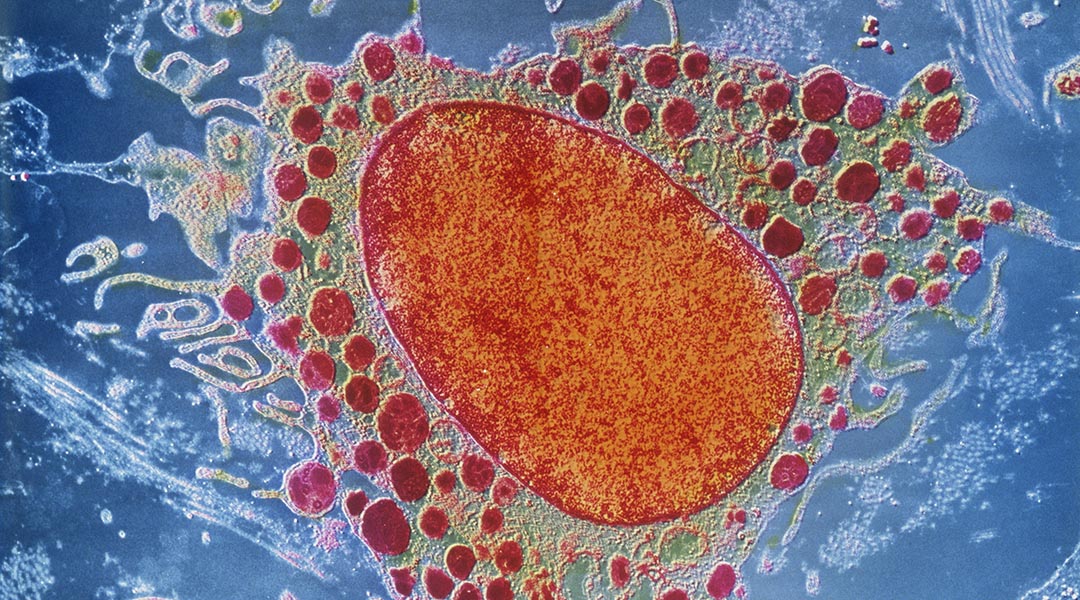

Feature image credit: SEM image of a white blood cell by Getty Images