Small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology might one day enable the selective disruption of any chosen gene. The potential therapeutic applications are mind boggling.

For research in this area to progress, a reliable system must be developed for safely delivering siRNA through the cell membrane, into the cell. Once there, the delivery system must be able to release the undamaged siRNA. Each of these two challenges represent significant technical hurdles in their own right.

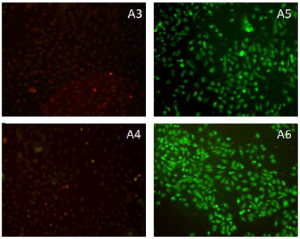

A4 shows the old delivery system, A5 and 6, the new.

In 2016, an international team reported the development of a delivery system for siRNA that was particularly focused on delivering to activated t-cells in the lungs to aid in the fight against asthma. That technology was hampered by low release of the payload at the delivery point. Recently published follow-up work, investigated the possibility that melittin, a toxin extracted from the European honey bee, might aid the siRNA release.

Melittin is able to disrupt the membrane of the delivery system thanks to the relatively low pH at the delivery target inside the cell. The more acidic environment activates the toxin, disrupting the delivery system membrane, which in turn releases the siRNA.

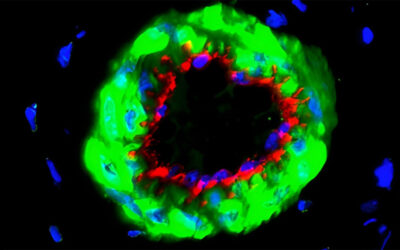

The team performed a number of experiments to determine whether the bee toxin did indeed aid siRNA release. Perhaps the most visually striking of these can be seen above. When the membrane of the delivery system is disrupted within a cell, that cell will fluoresce green. If not, a red color is expected.

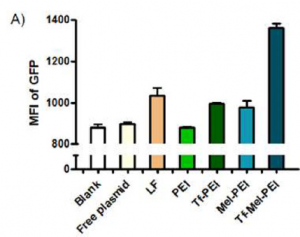

Breaking apart the membrane of the delivery system is a good first step, but the real test of efficacy is whether the payload can be used by the target cell. The team loaded their delivery system with a plasmid that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP), and added it to a cell culture. The results shown below indicate that significantly more green fluorescent protein was expressed by cells that had been treated with the new system.

The rightmost entry shows increased GFP expression thanks to the new delivery system

Given these promising results, the team hopes that this new platform might allow for the selective alteration of gene expression in lung cells. Further into the future, it is hoped that this research will lead to a new therapy for asthma sufferers.