Near-infrared imaging using optical contrast agents shows great potential for diagnosing breast cancer. It could increase specificity in combination with an established modality or even serve as the primary breast imaging tool.

Near-infrared imaging using optical contrast agents shows great potential for diagnosing breast cancer. It could increase specificity in combination with an established modality or even serve as the primary breast imaging tool.

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women worldwide. A diagnostic tool should ideally be able to detect breast cancer as early as possible, its sensitivity should be high. On the other hand, it should be able to distinguish between malignant and benign lesions with high specificity and thus reducing the need for biopsies. X-ray mammography has a rather low average sensitivity of only approx. 75% and a specificity of about 60 – 90%. In radio-opaque breast tissue sensitivity can even drop below 50%. Ultrasound is examiner-dependent and time-consuming, and MRI is expensive and has a greatly varying specificity, so both are not suitable for screening.

Optical imaging in the form of near-infrared (NIR) imaging seems to be a promising alternative. In contrast to conventional methods it has the potential to acquire information at the molecular and cellular levels. It poses no risk of ionizing radiation, the devices are relatively inexpensive, and handheld probe-based systems have been developed. On the basis of three studies performed by his group, Alexander Poellinger from Charité, Berlin (Germany) reviews the current status of optical breast imaging using extrinsic contrast agents.

In the “diagnostic window”, the molecules that most strongly absorb are oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin, allowing identification of areas with increased hemoglobin (e.g., malignant lesions with increased neovascularization). However, benign lesions and fibrocystic processes may also contain higher amounts of hemoglobin.

Some limitations of techniques relying on intrinsic contrasts can be overcome by the use of extrinsic contrast agents. To date, two contrast agents have been applied in human studies, indocyanine green (ICG), which is approved for clinical use, and omocianine, a non-specific ICG derivative with a lower binding affinity to plasma proteins than ICG. Both have been used for absorption and fluorescence imaging. However, data is still sparse, and only about 10 studies have been published so far.

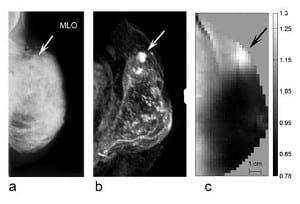

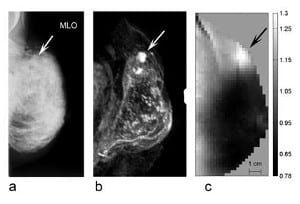

With its strong and rapid binding to macromolecules, ICG acts as a so-called blood pool agent, its distribution is predominantly intravascular. In malignant tumors, ICG bound to macromolecules can extravasate through the larger pores of tumor vessels. In one of their studies, using a time-resolved technique, Poellinger’s group investigated early and late fluorescence of breast lesions. Two technical novelties used in this study markedly improved contrast between malignant lesions and surrounding breast tissue: First, the generation of absorption-corrected fluorescence images resulted in a fairly homogeneous background, which typically is inhomogeneous due to blood vessels and glands. Second, they exploited concentration differences of ICG in tissues on late images. Since ICG in plasma rapidly binds to macromolecules, it acts as a macromolecular contrast agent. Tumor vessels have larger pores than vessels in normal tissue, allowing extravasation of molecules with a molecular weight of over 50 kDa. Thus, an increased concentration of ICG follows extravasation. In healthy tissue, the smaller vessel pores preclude extravasation of macromolecules with a molecular weight of approx. 20 kDa or more. On late images, acquired approx. 25 min after the end of contrast medium administration, ICG was nearly completely eliminated from blood and virtually no ICG was left in non-diseased tissue. In this study on 20 patients, the delayed fluorescence images showed markedly higher specificity than X-ray mammography (75% vs. 25%) while sensitivity was comparable.

Poellinger concludes that the use of optical contrast agents can considerably enhance the diagnostic yield of optical mammography. The initial results suggest that contrast-enhanced optical mammography might not only be of interest to increase specificity in combination with an established modality but possibly also to serve as the primary breast imaging tool in young women or women with dense glandular tissue. This applies especially to late fluorescence mammography using ICG.