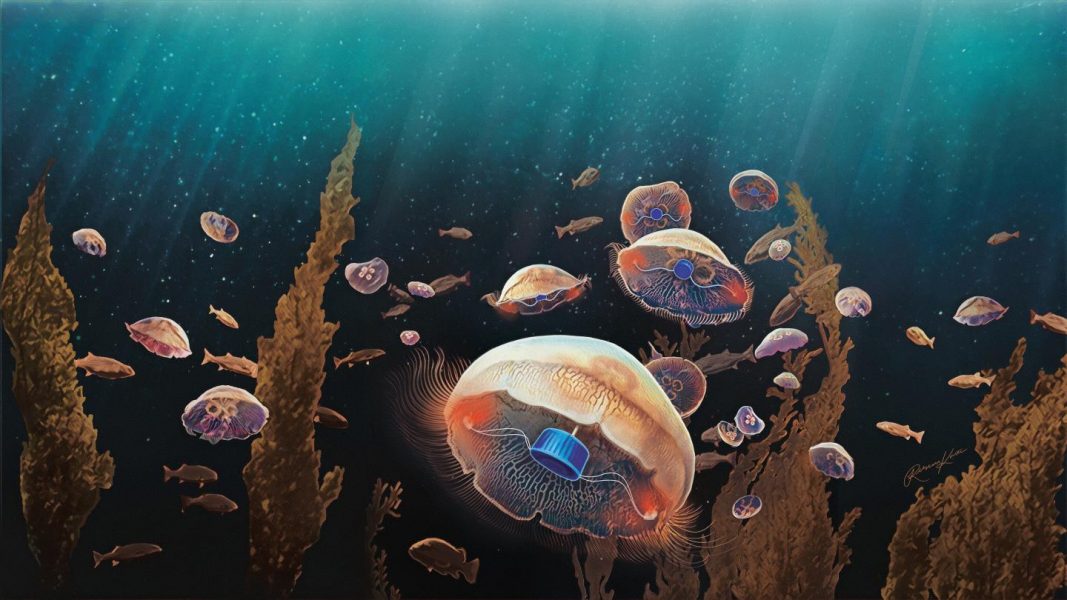

Researchers from Caltech and Stanford University have reported a tiny, microelectronic prosthetic that they have developed to enable jellyfish to swim more quickly and efficiently. To answer the resounding “why”, the team hopes that their bionic jellyfish might one day be useful in ocean exploration given their large populations and presence at depths ranging from the surface to the bottom of deep trenches.

The team of researchers led by Professor John Dabiri at Stanford also hopes to provide a new route to bioinspired robots. While copious amounts of research have gone toward developing robots that mimic living systems, purely mechanical systems that display fluid and precise movement require much more energy to accomplish the same tasks — not to mention the problems associated with energy generation, storage, and the ability to navigate unknown environments. “We haven’t captured the elegance of biological systems yet,” said Dabiri.

As such, equipping organisms with electronic components intersects research fields in which robots are made from entirely mechanical components and those made of purely biological materials. Dabiri has been involved in developing these hybrids over the last decade.

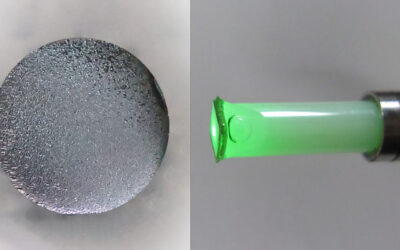

In the study, the team equipped jellyfish with a microelectronic controller pulsing at a frequency three times faster than the animals’ usual body pulses. Although the lazy, languid movements of jellyfish are optimal for catching prey, according to the researchers, they are capable of moving at a much faster speed. With the activation of the electronic prosthetic, the animals’ pulsing sped up, producing an increase in their swimming speed from 2 centimeters per second to around 4-6 centimeters per second.

According to the team: “In addition to making the jellyfish faster, the electrical jolts also made them swim more efficiently. Although the jellyfish swam three times faster than their usual pace, they used just twice as much energy to do so (as measured by the amount of oxygen consumed by the animals while swimming). In fact, the prosthetic-equipped jellyfish were over 1,000 times more efficient than swimming robots.”

Dabiri and his co-author, Stanford graduate student Nicole Xu, were also careful to ensure the jellyfish were not harmed during the process. When jellyfish become stressed they secrete a mucus, but this was not observed during the experiment and once the prosthetic was removed, they went back to their normal swimming behavior.

“We’ve shown that they’re capable of moving much faster than they normally do, without an undue cost on their metabolism,” Xu said in a press release published by Caltech. “This reveals that jellyfish possess an untapped ability for faster, more efficient swimming. They just don’t usually have a reason to do so.”

The team is optimistic that their new bionic jellyfish will greatly improve out ability to explore the ocean’s great unknowns. “Only a small fraction of the ocean has been explored, so we want to take advantage of the fact that jellyfish are everywhere already to make a leap from ship-based measurements, which are limited in number due to their high cost,” Dabiri said. “If we can find a way to direct these jellyfish and also equip them with sensors to track things like ocean temperature, salinity, oxygen levels, and so on, we could create a truly global ocean network where each of the jellyfish robots costs a few dollars to instrument and feeds themselves energy from prey already in the ocean.”

While still in its preliminary stage, Dabiri and Xu hope to create a small enough version of the prosthetic to embed into the jellyfish tissue and in addition to controlling swimming speed, guide the animal’s direction.