Researchers at the German Aerospace Center DLR (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt) are researching a morphing wing trailing edge. It can be smoothly transformed into any shape and will make conventional flaps redundant. The flaps on the wings of today’s commercial airliners are actuated via a complicated mechanism. Their arrangement and the resulting gap when they are extended compromises the aerodynamics, increases fuel consumption and contributes to inflight noise.

The new technology, on the other hand, is flexible. Remarkably, its movement is based on that of carnivorous plants. This enables the gap between the wing and the flap to be eliminated.

When looking for a suitable technical solution for deforming the trailing edge of a wing during flight, the venus flytrap proved to be a good source of inspiration. This is something of a surprise, but only at first glance. “The carnivorous Dionaea Muscipula needs to be able to close its trapping leaves very quickly to catch its flying insect prey,” says Benjamin Gramüller from the DLR Institute of Composite Structures and Adaptive Systems. “It does this by changing the pressure in the leaf cells and using a leaf-shape geometry optimised through evolution.”

Research has shown that the Venus Flytrap builds up tension through water pressure. When triggered – when a fly enters the trap – this can be quickly discharged. The trap then snaps shut. “We are now using the principle behind the plant’s movement for aeronautics applications,” adds Gramüller.

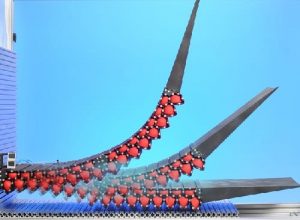

The DLR researcher and his colleagues have translated the cell system’s idea of using pressure to assume a desired shape on the trailing edge of a wing. To do so, they have developed the world’s first flap demonstrator, which is operated with compressed air and can flexibly assume aerodynamic shapes for cruising or landing. The plastic cells in the demonstrator have different sizes to form the appropriate shape for the trailing edge of the wing. Two layers of cells lie one on top of the other.

“To raise the edge, we pressurise the lower cell layer, and to lower it, we pressurise the upper one,” explains Gramüller. “The compressed air can be easily supplied from the existing compressed air system in an aircraft.” The DLR researchers have already been able to use the new flight technology to demonstrate that the desired flap shapes for take-off and landing can be achieved depending on how the compressed air is applied.

The aircraft is able to maintain itself in the air at low speed – for example, during landing – thanks to the increased lift coefficient from the extended flaps. The flaps increase the curvature of the wings during slow flight and hence compensate for the loss of speed.

In future, the researchers plan on testing their new flap technology in a wind tunnel. The PACS (Pressure Actuated Cellular Structures) research project is being carried out in conjunction with Airbus Defence and Space.