The impacts of carbon emissions on Earth’s climate are global, but the impacts of the hazardous co-pollutants released by fossil fuel combustion — including sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and airborne particulates — are mainly local.

In the United States, as elsewhere, low-income and minority communities are disproportionately impacted by pollution from power plants, refineries, and energy-intensive industrial facilities. Yet many environmental justice advocates remain skeptical about one of the most widely endorsed tools to curtail the burning of fossil fuels: carbon pricing.

Carbon pricing via carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems now covers more than one-fifth of CO2 emissions worldwide. It is not a stand-alone policy but rather is accompanied by a variety of other policies to spur the clean energy transition, including regulatory standards, public investment, and support for renewables. Carbon pricing complements these other policies by seeking to correct a fundamental flaw in energy markets: the enormous costs that climate change will impose on current and future generations is an “externality,” missing from the price of fossil fuels.

In the U.S., however, carbon pricing has yet to become part of the national climate policy mix, having been stymied not only by predictable opposition from the fossil fuel lobby, but also by misgivings among environmental justice advocates and their allies on the progressive side of the political spectrum.

Critics argue that where carbon pricing policies do exist, they have failed to bring about substantial reductions in emissions. Environmental justice advocates worry, above all, that carbon pricing could allow pollution “hot spots” — locations with exceptionally severe local pollution burdens — to persist in disadvantaged communities. What is more, the higher fuel prices triggered by carbon pricing generally hit low-income households hardest. Finally, some critics contend that carbon pricing commodifies nature, transforming something that ought to be treated as sacred into something that can be bought and sold.

A hard limit on carbon emissions

The reason that existing carbon pricing systems have not brought about more impressive reductions in emissions is that the prices have been set too low. No one can say what is the “right” price on carbon since price responsiveness always depends on unknowns, such as the future prices of renewables, fluctuations of the business cycle, and what other policies are deployed alongside the carbon price.

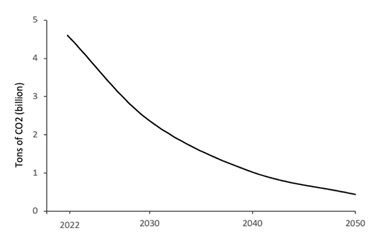

We have a clearer picture, however, of how far and fast we need to curtail emissions to achieve the goal set by the Paris Agreement to limit average surface temperatures to 1.5–2 °C above their pre-industrial level. Meeting this target will require major energy-consuming nations to attain net-zero carbon emissions, or something close to it, by mid-century.

If 10% of this ambitious goal is achieved by carbon sequestration through better land management and other measures, this would mean that we must cut emissions from fossil fuels by 90% over the next three decades, a pace of roughly 8% per year (see figure). No country has succeeded in doing this in the past.

There is a straightforward way to anchor the carbon price to this trajectory: put a hard limit on the total quantity of fossil carbon that we allow to enter the economy from extraction and imports. The limit would tighten year by year along the required path, with permits to bring fossil fuels into the economy issued up to this amount.

At every pipeline terminal, every tanker port, and every coal mine head, corporations would have to surrender one permit for every ton of CO2 that will be emitted when their fuel is burned. Rather than being handed out free to corporations as is often done in cap-and-trade systems, the permits can be auctioned quarterly, as currently done in the northeastern U.S. states in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative for power plants.

Under this policy, the emissions-reduction trajectory would determine the carbon price, rather than setting a price and simply hoping that it does the job.

The environmental justice guarantee

A key feature of carbon prices — lauded by economists — is that they let businesses and consumers decide where and how to cut their own use of fossil fuels. Faced with higher fossil fuel prices that reflect the environmental harm caused by carbon emissions, users can decide how best to respond, curtailing emissions wherever this is cheaper than paying the higher price. Assuming they choose the most cost-effective responses, the net effect is to minimize the total cost of achieving the desired reduction in emissions.

This same flexibility is problematic from an environmental justice standpoint, however, because it allows polluters in hot spots to continue emitting, or even increase their emissions, just by buying permits or paying the carbon tax. As a result, pollution exposure disparities can persist or perhaps even widen.

To see how, consider the electric power sector. A carbon price encourages electricity producers to switch from coal to natural gas, since this produces less CO2 per kilowatt hour. Coal-fired power plants tend to be located relatively far from urban population centers, but gas-fired plants often are located closer to them, in or near communities with below-average incomes and above-average percentages of racial and ethnic minorities. In the first five years of California’s cap-and-trade system, for example, carbon emissions rose substantially at two major gas-fired plants in metropolitan Los Angeles as their owners bought the needed permits.

To guard against such outcomes, carbon pricing policies should incorporate an environmental justice guarantee mandating that exposure to toxic co-pollutants in front line communities will be reduced at least as much as the overall decline in carbon emissions.

Screening tools can be used to identify communities at risk, and air-pollution monitors installed in these communities to measure changes once the policy goes into effect. If local co-pollutant exposure falls in pace with the overall carbon emissions, the guarantee simply acts as an insurance policy. In any places where this does not happen, the guarantee kicks in to ensure that it does.

Climate protection dividends

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to carbon pricing is that higher fuel prices are highly unpopular with consumers. This helps to explain why political leaders typically set carbon prices too low to have a big impact on fuel prices — or on emissions.

Fuel costs loom large in household budgets, and many people already struggle to make ends meet. Furthermore, in industrialized countries, lower-income households generally spend a larger share of their income on fuels, even though wealthier households typically consume far more carbon by virtue of their higher purchasing power. On its own, in other words, carbon pricing is tantamount to a regressive tax.

There is a crucial difference, however, between carbon pricing and the more familiar fuel price increases that are driven by production quotas set by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries or by other supply disruptions, like Russia’s war in Ukraine.

In the case of carbon pricing, the extra money paid by consumers does not end up in the profits of fossil fuel corporations — unless, of course, they get free permits in a cap-and-trade system. Instead, the revenue from permit auctions or a carbon tax initially goes to the government, which can choose to recycle all or most of the money straight back to the public.

Returning the carbon revenue equally to everyone as climate protection dividends (a.k.a. carbon dividends) would reverse the regressive impact of carbon pricing: lower-income households will get back more than they spend in higher fuel prices; middle-income households will break even; and wealthy households, with their outsized carbon footprints, will pay more than they get back.

Canada recently introduced climate protection dividends in four provinces, including Ontario. In the past year, Austria followed suit, calling the payments a “klimabonus”. It is still too early to gauge the public response, but most people are happy to get checks in the mail (which these days typically come via an electronic transfer into bank accounts).

Climate protection dividends are a type of universal basic income, founded on the principle that everyone is an equal co-owner of the biosphere’s limited carbon-absorption capacity, and thus everyone has an equal claim to revenue generated by charging for its use. Politically, universal dividends can help safeguard the durability of carbon pricing over the decades needed to complete the clean energy transition, much as universal coverage has safeguarded social security and national health systems.

Environmental justice advocates likewise invoke an ethic of universality when they rebut accusations of NIMBYism (not-in-my-back-yard insularity) with the reply, “Not in anybody’s back yard”, insisting that the burdens of pollution should not be concentrated in specific communities.

No trading, no offsets

To those critics of carbon pricing who object that it commodifies nature, transforming the integrity of the environment into something that can be bought and sold, we respond: not everything with a price is a commodity.

Cities routinely use parking meters along with regulations to prevent congestion on public thoroughfares. This does not turn parking places into a commodity; it simply means their use is no longer free. Similarly, carbon pricing charges for parking CO2 in the atmosphere. To allow emissions free-of-charge values their impacts on present and future generations at zero. This is not treating nature as sacred: it is treating it as worthless.

It is true that in cap-and-trade systems, permits become commodities that corporations can trade among themselves. But no trading is necessary if the permits are auctioned rather than given away to corporations free-of-charge, since firms can buy the number of permits they want at the auction price. Nor is there any need to allow financial intermediaries or others apart from fossil fuel firms to trade in permits with the speculative aim of buying low and selling high. When we think of other kinds of permits – like driving permits, parking permits, building permits, and hunting and fishing permits – none of them are tradeable. They are not commodities. There is no good reason for carbon permits to be, either.

Carbon offset markets carry commodification a step further. Offsets allow a firm to avoid buying permits (or paying the carbon tax) by buying carbon credits from others who have done things like planting trees, or refraining from cutting a forest, that ostensibly compensate for the firm’s own emissions. Offsets are subject to well-known and intractable problems of additionality (would the offsetting action have occurred regardless?), verifiability (did it really happen?), and perishability (will its effect last as long as atmospheric CO2?).

Offsets, in short, would turn the carbon cap into a sieve. Efforts to augment carbon sequestration are an important piece in the climate policy mix, but these should be undertaken in addition to keeping fossil fuels in the ground, not instead of it.

There is no intrinsic conflict between carbon pricing and environmental justice. Policies that incorporate a hard limit on emissions, safeguards against pollution hot spots, climate protection dividends, and no permit trading or offsets would effectively address the concerns raised by critics of carbon pricing. The key to reconciling carbon pricing and environmental justice is to design policy with this goal clearly in mind.

Reference: James K. Boyce, Michael Ash, Brent Ranalli, Environmental Justice and Carbon Pricing: Can They Be Reconciled, Global Challenges (2023). DOI: 10.1002/gch2.202200204

Feature image credit: Marcin Jozwiak on Unsplash