Severe water shortages already affect many regions around the world, and are expected to get much worse as the population grows and the climate heats up. Beverage companies have been preparing for the changing situation for some time.

But a new technology developed by scientists at MIT and the University of California at Berkeley could provide a novel way of obtaining clean, fresh water almost anywhere on Earth, by drawing water directly from moisture in the air even in the driest of locations.

Technologies exist for extracting water from very moist air that have been deployed in a number of coastal locations. And there are very expensive ways of removing moisture from drier air. But the new method is the first that has potential for widespread use in virtually any location, regardless of humidity levels, the researchers say. They have developed a completely passive system that is based on a foam-like material that draws moisture into its pores and is powered entirely by solar heat.

Fog harvesting, which is being used in many countries including Chile and Morocco, requires very moist air, with a relative humidity of 100 %, explains Evelyn Wang, associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. But such water-saturated air is only common in very limited regions. Another method of obtaining water in dry regions is called dew harvesting, in which a surface is chilled so that water will condense on it, as it does on the outside of a cold glass on a hot summer day, but it “is extremely energy intensive” to keep the surface cool, she says, and even then the method may not work at a relative humidity lower than about 50 %. The new system does not have these limitations. It is “completely passive — all you need is sunlight,” with no need for an outside energy supply and no moving parts.

In fact, the system doesn’t even require sunlight — all it needs is some source of heat, which could even be a wood fire. “There are a lot of places where there is biomass available to burn and where water is scarce,” MIT postdoc Sameer Rao, says.

The key to the new system lies in the porous material itself, which is part of a family of compounds known as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Invented by the UC Berkeley professor of chemistry Omar Yaghi two decades ago, these compounds form a kind of sponge-like configuration with large internal surface areas. By tuning the exact chemical composition of the MOF these surfaces can be made hydrophilic, or water-attracting.

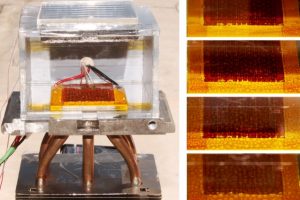

This proof-of-concept device demonstrates a new system for extracting drinking water from the air. Images courtesy of the researchers

The team found that when this material is placed between a top surface that is painted black to absorb solar heat, and a lower surface that is kept at the same temperature as the outside air, water is released from the pores as vapor and is naturally driven by the temperature and concentration difference to drip down as liquid and collect on the cooler lower surface.

Tests showed that one kilogram of the material could collect about three quarts of fresh water per day, about enough to supply drinking water for one person, from very dry air with a humidity of just 20 %. Such systems would only require attention a few times a day to collect the water, open the device to let in fresh air, and begin the next cycle.