Similar to how a person decorates their house, all cells in the body decorate their own surrounding environment, known as the extracellular matrix. Even when cells are removed from their “homes,” the extracellular matrix retains memories of the cell that occupied it.

Claudia Loebel, an assistant professor in the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, offers this analogy to explain how cells interact with their environment. She and her research group use spongy, water-soluble polymers called hydrogels to recreate the extracellular matrix of specific organs, like the lung, in the lab.

Precisely engineered organ models—called organoids—allow researchers to study organ development, as well as the diseases that affect these organs, outside the body. They have the potential to mimic the organs of individual patients at a particular stage of a disease. This would enable drug testing on the organoid instead of the patient and potentially reduce the need for small-animal models.

Loebel received a Packard Fellowship in 2023 for her research on the extracellular matrix and is this year’s recipient of Macromolecular Rapid Communications Junior Researcher Award. She talked to us about her motivations, research, and the future of biomaterials.

What motivated your shift from medicine to biomedical engineering?

It was kind of a slow shift, and I never anticipated it when I entered medical school. I really had no idea what research was [back then]. In my family, there were no academics, no one with a background in medicine or science, and when I was in my third year as a medical student, I learned that I could do research in Germany. I was curious, and I started research in a cancer biology lab.

I suddenly realized how exciting this was! I spent so many hours in the lab besides going to medical school. This is when I realized I really enjoy being in the lab, at the bench. Towards the end of medical school, I became interested in orthopedics [correcting bones and muscles], and this is when I realized that for many orthopedic problems, we need tissue engineering, which embodies both engineering and fundamental cell biology.

What is the overarching goal of your research?

We use different chemistries to recreate certain aspects of a cellular microenvironment [using biomaterials such as hydrogels]. We’re thinking about cells in their tissues and use engineering tools to recreate this within the lab. We believe that with these models, we can capture or get a better picture of how cells perceive, respond, and communicate with their environment and with each other within the body––this really complex cellular microenvironment.

My research is highly collaborative. Together, with biologists and clinicians, we use our tools to get a better understanding [of how cells do this], which will help us identify new treatments and therapeutic approaches.

What is the extracellular matrix, and why is it important to understand how cells interact with it?

This is the main objective in my lab––everything we do is somehow related to the extracellular matrix. In any tissue, almost every cell is surrounded by it. It really depends on the organ, but the extracellular matrix is basically a mixture of different proteins and carbohydrates. And, of course, there are also small molecules and cofactors.

Maybe 30 or 50 years ago, scientists thought the extracellular matrix is simply a scaffold for cells. But over the last few years, we have learned that the extracellular matrix is critical because it provides mechanical and biochemical signals to cells, which are in direct contact with it.

What is an organoid?

We don’t really have a definition that everyone is using. Organoids are basically stem cells or progenitor cells, that, when in the right microenvironment, self-organize. They proliferate, self-organize, and assemble into these organ-like structures when the architecture is right.

There are some loose definitions out there, and there’s a lot of work in this area to better define organoids. I think this may need a little more time.

Why is it important to construct accurate organoids?

It’s important because, first of all, every organ is different. Every organ has a complex, high-precision microenvironment. We’re thinking about the architecture of the organs.

For example, think about how complex a lung is—air enters the trachea and is distributed throughout tiny air sacs called alveoli, and then oxygen is taken up by the blood. It is such a complex microenvironment, which is what makes it so fascinating.

We need engineering tools to actually be able to capture some of these complexities. This is why I think it is very important to reconstruct these [in the lab].

Could organoids potentially replace small-animal models to study diseases?

There is a discussion in the field, and there are certainly advantages and disadvantages. When we’re thinking about the lung or another organ, we can use human cells to make a human organoid [in the lab]. I wouldn’t say we can completely replace small-animal models yet, but perhaps this is the future.

How do you engineer a lung organoid? Does it actually resemble a lung?

No, but it resembles certain aspects of the lung.

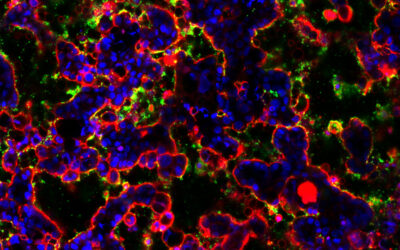

When we make lung organoids, we use stem cells called type 2 alpha progenitor cells, which have the ability to proliferate and differentiate into type 1 lung cells. These cells line the alveoli, tiny air sacs that allow oxygen into the lungs.

[To recreate this in an organoid,] we take stem cells from mice or humans, and we put them in a hydrogel-like matrix called Matrigel, which is basically a mixture of extracellular matrix proteins derived from mice. This gel contains lots of different extracellular matrix proteins and growth factors.

When we put these stem cells into Matrigel, they proliferate and form cyst-like structures, like an alveolus in the lung. Then, they can differentiate into more specific cells, like a lung alveolus-like cell. But you need to keep in mind that the alveolus has a lot of additional cells like immune cells, mesenchymal cells, and endothelial cells. And of course, if these cells are not from the same lineage, we have to add them in order to resemble an organoid. This is all possible these days, but we still have a long way to go. In my lab, we basically do this in a more controlled environment.

How long does it take to make a lung organoid? What are the main considerations and hurdles?

Typically, it takes 2–3 weeks until you can use them for certain applications. If you ask anyone in the field, the main hurdle is that we still need Matrigel. Matrigel is fantastic, but the problem is that it is mouse derived, so it’s animal derived. We would never be able to use it for clinical translation [in humans]. We will never be able to implant Matrigel from a mouse into a human.

Also, the composition of Matrigel is highly variable. This means when you order Matrigel once, and again half a year later, it will be different. One of the biggest goals of my lab is to develop polymers––hydrogels––that can hopefully at some point replace Matrigel.

From an engineering perspective, we still don’t really understand what Matrigel is doing. We don’t really know what it is about Matrigel that actually helps these organoids grow. This hurdle is the big question [in our lab]. Is it the signaling? Is it physical support or mechanical properties? We are dissecting all these different things in the lab to understand what Matrigel is.

Are you using the organoids to study disease or testing drugs on them?

We’re not looking at this aspect just yet, but this is where our collaborations are so important. We developed this platform mostly for lung organoids, but we are now in contact with many biologists who are saying, “Oh, I really like your homogeneous organoids. Can we do this with our organoids?”

How does the extracellular matrix store memories?

It is one of my visions to understand extracellular matrix memory. Going back to my analogy, when you think about the new apartment you decorated, when someone is coming into your house, they can learn a lot about you and what you care about. For example, in the last 10 years, we found that when you put cells on a very stiff substrate, like tissue-culture plastic, and then you put them in a very soft environment, they still behave as though they are on a stiff substrate. So we know that cells have a mechanical memory.

Cell memory has also been critically important when we think about the immune system and vaccine development. This is because immune cells have this memory that we are using to fight diseases. The extracellular matrix is underrated in that it is the cells that are making it. This is how I believe they’re storing certain signals in there, similar to the house. This memory storage will help us in the long term to identify better therapies that can target the extracellular matrix.

What do you consider your most impactful research finding to date?

It all goes back to the extracellular matrix. When we develop biomaterials and hydrogels, we basically use them to mimic the extracellular matrix. Many researchers have done this, and it has yielded in a lot of very important observations. I thought about this when I started my postdoc.

We always put cells inside these hydrogels or biomaterials that we aim to mimic the extracellular matrix. But cells are making their own extracellular matrix. This is their job. I showed that cells are making their own extracellular matrix, which kind of shields them from the engineered hydrogels. This was a major finding because it basically showed that we cannot just simply engineer these extracellular matrices and think that cells would say, “Ok, this is my extracellular matrix. I’m going to use it.” No, they’re making their own.

And now, instead of just thinking about the two-way signalling between the cell and extracellular matrix, we basically have pioneered this triangle between the engineered extracellular matrix [made from the hydrogel] with cells and the extracellular matrix they secrete on their own. This is very important. We’ve shown that it is really this newly secreted extracellular matrix that provides cells with the opportunity to make an organoid.

How will your research ultimately benefit doctors and patients?

We’re thinking about lung fibrosis, which is the scarring of the lung tissue, a very devastating disease. Patients typically die within five years of diagnosis because once you have scars in your lung, it’s very difficult to improve. We have treatments, but they’re not curative.

Fibrosis is a disease of the extracellular matrix as well because it’s scarring collagen, one of the most abundant proteins in the extracellular matrix. One of our major goals is to use our engineering tools to better understand how fibrosis is initiated and how the extracellular matrix participates in that.

I believe that this better understanding will help us to develop better diagnostic tools, or at least know what we are looking for. This will then help develop better treatments that hopefully at some point can be curing.