From the appearance of the first stone tools used by many hominid species about 2.5 million years ago until the invention of agriculture and animal husbandry 15 thousand to 10 thousand years ago, our ancestors lived as hunter gatherers. This period is known as the Paleolithic era, from ancient Greek meaning “Old Stone Age”.

For a long time, scientific research regarding the eating habits of Paleolithic hunter gatherers focused on animal consumption. It was widely believed that our ancestors were exclusively highly specialized hunters of large mammals, partly because plant remains at excavation sites were not always well-preserved. Unlike bone, plants degrade easily mainly because they have a large water content. With the exception of seeds, pollen, and the shells of certain fruits, it is therefore not easy to find preserved plant remains.

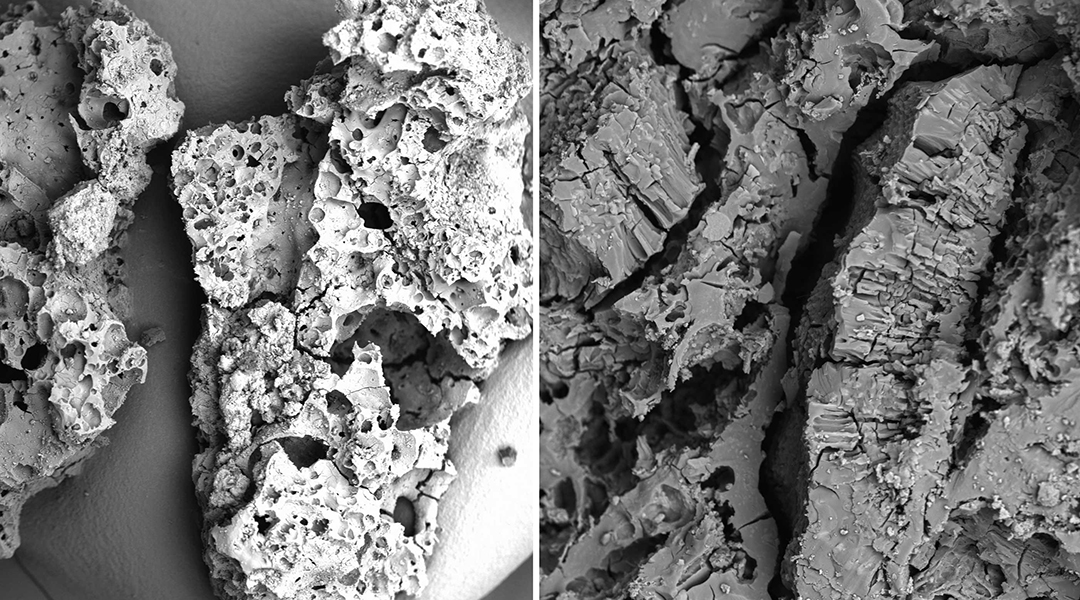

However, scientists have recently begun to examine the use of plants more closely in Paleolithic diets, both those harvested and those derived from some sort of pre-agriculture. They started with charred remains, which are better preserved because the charring process can prevent the dissolution of organic matter.

Finding processed plant remains in Paleolithic sites

In a recent study led by scientists at the University of Liverpool, the team focused on the processed and charred remains of some plants found in two locations: the Franchthi Cave in Greece and Shanidar Cave in the Northwest Zagros Mountains in Iraq. These findings indicate that human knowledge of edible plants predates the earliest evidence of plant cultivation by several tens of thousands of years.

Ceren Kabukcu, a postdoctoral research assistant in the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool and the lead author of the article, has been studying plants in ancient diets since she was a student explained how archaeobotanical remains — that is, archaeological plant remains — are crucial to reconstructing “the everyday activities of past hunter-gatherers, such as cooking, cleaning, lighting fires, using all the plant resources in their environments”.

“Plants are crucial to our survival both today and in the past,” she continued. “They provide nutrition and essential vitamins, they can be easy to store, and they provide raw materials for making clothes, bedding, and fuel for heating. The work that I do, and those done by many other archaeobotanist, allows us to understand the complex decisions our ancestors made in choosing which plants to eat, or to collect for their everyday needs, and the impacts they had on the resources in their environment.”

The food remains found in the two cave sites and reported in this study currently represent the first direct macrobotanical evidence of plant food preparation in the eastern Mediterranean.

It can be assumed that as early as the Paleolithic period, humans knew and implemented resource management strategies. “In some cases, we can see protection and management of woodlands or other plant resources by early hunter-gatherers or early farmers that enabled them to rely on these crucial resources through the thick and thin,” she explained.

It also appears that these techniques and knowledge acquired by our ancestors did not develop, as is often the case, as a result of a climatic-environmental crisis, such as a shortage of resources. On the contrary, it seems that they were partly independent of seasonal or climate-driven, fluctuations in the availability of plants and animal prey.

“We can also depict the diversity of ways in which plants were incorporated into past diets across many different regions, all with different environments, climates, and natural resources,” said Kabukcu. It can be inferred that although available resources played a major role in the choice of plants to feed on, there already existed in Paleolithic populations a taste or a preference for certain foods over others.

This work, which is likely to be the first in a long series, according to Kabukcu, in which the purpose “was to trace changes in plant use at several sites in Southwest Asia and parts of Mediterranean Europe considering a long time span, from about 75,000 to 10,000 years ago”.

An ancient knowledge of plants

The charred remains found in these two sites in Greece and Iraq, which are not seeds or nutshell fragments but food items that included various types of plants that had been soaked, crushed (or broken) and cooked—in other words the food shows evidence of being processed in a way that Kabukcu and team believes was done to remove toxic and unpalatable components, to make the food more edible.

”These findings expand the range of plant food items considered ‘edible’ in the Palaeolithic record,” added Kabukcu. “They also highlight cognitive complexity in early humans expressed through their plant cooking practices and an associated culinary culture as early as the Middle Palaeolithic, the origins of which likely predates our findings.”

The most common ingredient identified was a group of wild vetches, which have a bitter taste due to the alkaloids in their seed coats, which if left untreated could cause stomach upsets. Given that bitter taste can often indicate toxicity, it can be deduced that our ancestors knew how to distinguish edible plants from potentially deadly ones, as well as how to process them to remove dangerous substances.

Microscopic examination found the remains consisted of legumes supplemented with starch-rich tubers and seeds, including some with a bitter taste and astringent properties, that is, with anti-inflammatory effects, such as almonds, pistachios, and wild mustard.

“We found this type of plant culinary preparation in all phases of occupation [of the caves], including Neanderthal and early modern occupation levels at Shanidar, and later occupations at Franchthi. The use of cooking techniques to make plant foods edible has a much deeper and longer ancestry than previously thought,” Kabukcu explained.

These results may have further implications in the study of the eating habits of Paleolithic humans, such as encouraging the integration of archaeobotanical studies into the study of archaeological sites.

“Not least because it is clear that beyond cooking, a closer evaluation of the flavor profiles of plant foods and even their textures could offer incredible insights into the daily lives of hunter-gatherers of the past, allowing us to see more cultural aspects of diet,” added Kabukcu. “This diversity of environments in which our ancestors lived and understanding their decisions gives us insights into our potential for change and adaptability.”

Reference: Ceren Kabukcu, et al., Cooking in caves: Palaeolithic carbonised plant food remains from Franchthi and Shanidar. Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 November 2022

Feature image: Charred plant remains from the Paleolithic area found in a cave. Credit: Ceren Kabukcu