With the advent of the birth control in the 1960s, women’s reproductive health changed forever. Over the years, female contraception has developed to provide safer and effective means of preventing unwanted pregnancy. However, the fact that contraceptive measures are targeted solely for women has continued to raise the question of burden.

“Many existing contraceptive methods come with side effects or are invasive,” explained Juliane Simmchen, professor of analytical chemistry at TU Dresden. “In some individual cases, […] the side effects don’t outweigh the benefits of birth control.

“The male side of this equation has been neglected for decades,” she added. “The social expectation for men is still bound to virility, and male contraceptives are clearly not a focus in this sense. As a result, this topic has not gotten much public attention or funding over the last few decades.”

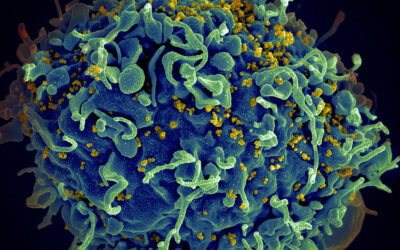

Copper has long been used in contraceptives due to its ability to hinder the motility of sperm cells. “Copper has been known to work very reliably as a female contraceptive in the form of an IUD, the drawback is that it requires a surgical procedure,” said Simmchen. “Until now, copper has not been explored as male contraceptive agent.”

Though research into available contraception options for the male reproductive system are currently limited to condoms and vasectomies, research in this area is picking up. In a recent study published in Advanced NanoBiomed Research, Simmchen, an expert in micro-and nanotechnology, and her collaborator Veronika Magdanz, group leader at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia, developed a spermicide using copper microparticles.

Most spermicides contain a compound called nonoxynol-9, which prevents pregnancy by blocking the entrance of the cervix and hindering the sperm from reaching the egg. Used alone, a spermicide is roughly 72% effective and come with some minor side effects in some individuals, such as irritation and an increased risk of urinary tract infections. New EU regulations will in the future require EMA approval for use spermicide in condoms, which could make regulatory processes around these products more complicated and costly — several producers are already considering taking their products off the market as a result.

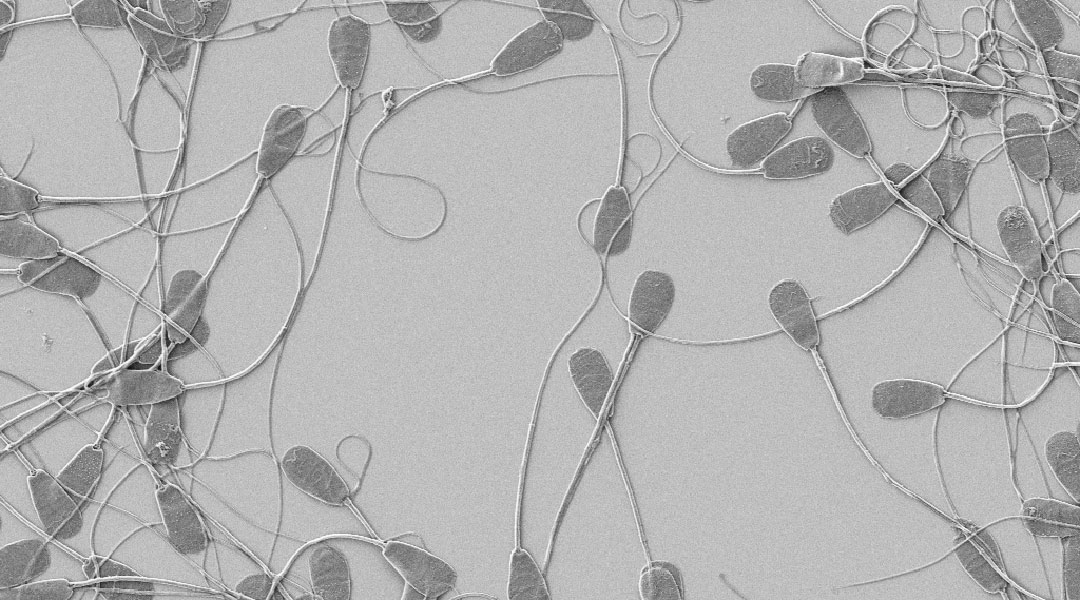

In their study, the researchers created particles of three different sizes (0.2 μm, 2 μm, and 7 μm) and studied how their sizes relate to their ability to inhibit sperm cells. “The copper particles release copper ions (Cu2+) that cause alterations in the metabolic properties of sperm that inhibits their motion and viability,” explained Simmchen. “In addition, copper might provide bactericidal effects, which could serve as an additional benefit to avoid transmittance of bacterial infections through intercourse.”

In addition to size, different particle concentrations were tested, measuring the number of mobile sperm cells after specific time intervals and comparing them to a copper-free control sample. It was found that the smaller the particle and the higher the concentration the greater the impact on hindering sperm. The size of the particles influences the solubility equilibrium of the copper ions released from the particles, leading to a higher concentration and a faster action for smaller particles.

While the results are promising in laboratory tests, the contraceptive is still a long way from widespread use. “The success of copper IUDs points toward a positive outcome for our future tests, but tests on human sperm, best forms of application, and possible side effects are still required,” said Simmchen.

Reference: Purnesh Chattopadhyay, et al., Size dependent inhibition of sperm motility by copper particles as a path towards reversible male contraception, Advanced NanoBiomed Research (2022). DOI: 10.1002/anbr.202100152