As the death toll from the new strain of coronavirus that originated in Wuhan, China, continues to rise — reaching 170 on January 30 — scientists around the world are scrambling for information on the virus that can help lead to a vaccine.

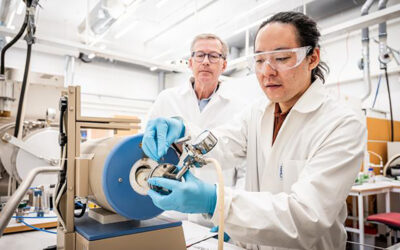

Earlier this week, in one such effort to provide researchers the world-over with crucial information, scientists from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Australia, successfully grew the new strain of coronavirus — 2019-nCoV — from a patient sample.

One of the lead scientists in the study, Dr. Julian Druce of The Royal Melbourne Hospital, spoke of the significance of this in a press release from the University of Melbourne.

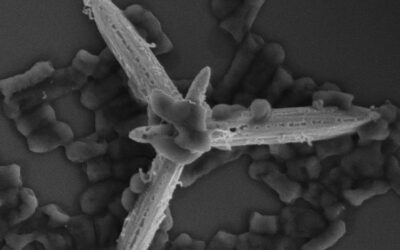

“Chinese officials released the genome sequence of this novel coronavirus, which is helpful for diagnosis, however, having the real virus means we now have the ability to actually validate and verify all test methods, and compare their sensitivities and specificities — it will be a game changer for diagnosis.”

What the researchers hope is that an antibody test can be generated using information gained from the lab-grown virus.

“An antibody test will enable us to retrospectively test suspected patients so we can gather a more accurate picture of how widespread the virus is, and consequently, among other things, the true mortality rate,” said Dr. Mike Catton, Deputy Director of the Doherty Institute, in the same press release.

But the genome sequence of 2019-nCoV, recently released publicly by China, will have other uses beyond virus detection.

A vaccine on the horizon?

On the other side of the world in San Diego, scientists at Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Inc. are using this genome and the latest technology to rapidly produce a vaccine.

Whilst normally vaccines take years to develop, scientists at Inovio hope to have the first human trials of their vaccine underway by the summer. This is down to a new approach to how vaccines are made that exploits the genetic information of a given virus.

Speaking to BBC news, Kate Broderick of Inovio explained, “Our DNA medicine vaccines are novel in that they use DNA sequences from the virus to target specific parts of the pathogen which we believe the body will mount the strongest response to.

“We then use the patient’s own cells to become a factory for the vaccine, strengthening the body’s own natural response mechanisms.”

Inovio are by no means the only group with a vaccine in mind. Back at the Peter Doherty Institue of Infection and Immunity, Dr. Catton gave further uses of their envisioned antibody test, “[The antibody test] will also assist in the assessment of effectiveness of trial vaccines.”

Global initiatives

The research being carried out at Inovio and elsewhere is funded by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), set up after the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and is being closely monitored by the WHO.

The rapidity of the global scientific community’s response to the coronavirus outbreak, along with China’s rapid sequencing and release of the virus’ DNA, are all testament to lessons learned from past coronavirus outbreaks.

The painful memories of the 2002–2004 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), another strain of coronavirus that also originated in China, are all too recent with 2019-nCoV, and the ways in which SARS was handled.

But some things have since changed in the two decades since SARS; back then, it took authorities in China three months to report the outbreak to the WHO, with national media showing initial reluctance to report such an outbreak. With this new coronavirus, however, notifications and information were quicker, earning praise from the WHO, despite criticism from some.

One things is clear, though: with new information on 2019-nCoV coming thick and fast, and with open scientific resources such as the virus’ genome in an age of rapid communication, the world is technologically better equipped to tackle outbreaks than it was in the past.

As scientists continue to mobilize in their fight against this current outbreak, the WHO are once again meeting on Thursday to determine if the outbreak constitutes a global health emergency.

Part of this article was adapted from a press release by the University of Melbourne, Australia.