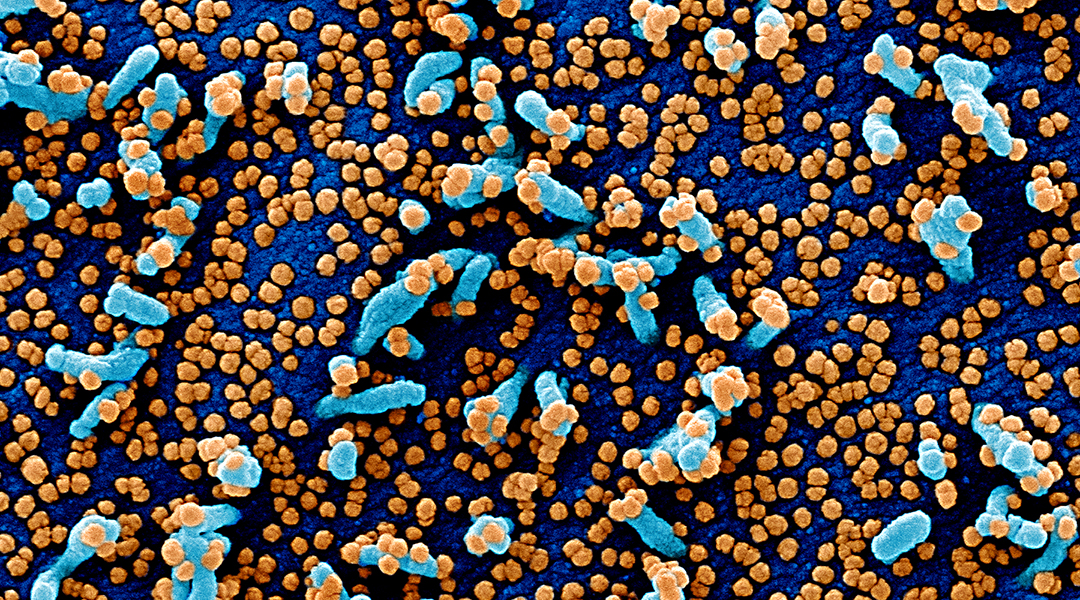

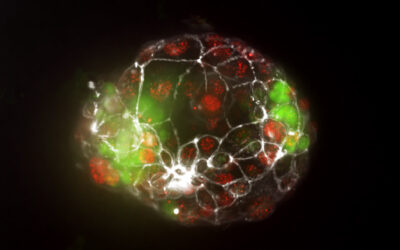

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a VERO E6 cell (blue) heavily infected with SARS-COV-2 virus particles (orange). Image credit: NIAID

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and in nature, it also serves a practical purpose. Many plants and animals use mimicry to trick both prey and predators, but it takes on a deadly form when viruses employ similar strategies.

Viruses have adapted an arsenal of elegant and ever-changing strategies to evade detection by the immune system, one of which is to produce mimics of human immune proteins, such as cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors, that play a vital role in the body’s immune response. This allows them to promote infection and remain unseen — and therefore unchecked — by the host’s body.

“Mimicry is a more pervasive strategy among viruses than we ever imagined,” said Sagi Shapira, assistant professor of systems biology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. “It’s used by all kinds of viruses, regardless of the size of the viral genome, how the virus replicates, or whether the virus infects bacteria, plants, insects, or people.”

Shapira is part of a team of scientists who published a new study in the journal Cell Systems, which demonstrates that coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2 are adept at this, imitating human immune proteins that have implications in severe cases of COVID-19.

Using powerful computers and a program similar to 3D facial recognition software to match viral proteins with their immune protein mimics, the team scanned more than 7,000 viruses and over 4,000 hosts and uncovered 6 million instances of viral mimicry.

While this underscored the phenomenon’s prevalence, the team was surprised to find that some families of viruses, such as Papilloma and retroviruses, use it less than others. The coronavirus family on the other hand was found to exhibit a high level of diversification and structural promiscuity in the human proteins they mimic, with over 150 protein examples identified in the current study.

Interestingly, these include many proteins that control blood coagulation or activate plasma proteins called complements, which help target pathogens for destruction and increase inflammation in the body.

“We thought that by mimicking the body’s immune complement and coagulation proteins, coronaviruses may drive these systems into a hyperactive state and cause the pathology we see in infected patients,” said Shapira.

In a separate paper published in Nature Medicine, the Columbia researchers found evidence that functional and genetic dysregulation in immune complement and coagulation proteins are associated with severe COVID-19 disease. They found that people with macular degeneration (which is associated with enhanced complement activation) were more likely to die from COVID-19, that complement and coagulation genes are more active in COVID-19 patients, and that people with certain mutations in complement and coagulation genes are more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19.

Since that paper first appeared this spring in a preprint, other researchers have also found links between complement and COVID severity and several clinical trials of complement inhibitors have been initiated. Shapira says the investigation of viral protein functions and mimicry suggests that learning about underlying virus biology could be one way to gain insights into how viruses cause disease and who may be at greatest risk.

“Viruses have already figured out how to exploit their hosts,” Shapira says. “By studying viruses we can not only reveal fundamental principles in biology but also how they perturb cellular homeostasis and cause pathology. The hope is that one day we may be able to use this knowledge to fight back.”

“Beyond COVID-19, the information we’re gathering about how individual viral proteins work across all viruses on Earth may one day be leveraged as building blocks in medical and agricultural interventions.”

Reference: Gorka Lasso, et al. A Sweep of Earth’s Virome Reveals Host-Guided Viral Protein Structural Mimicry and Points to Determinants of Human Disease, Cell Systems (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.09.006

Adapted from press release provided by Columbia University Irving Medical Center