Image credit: Thomas Iversen on Unsplash

Say “domestic animal” to anyone and the idea that will pop into their head will likely vary depending on culture and society. Do I mean a pet or livestock? A personal security guard or a personal helper? A means of transport or baggage carrier? It depends when you were to ask this question, too. Depictions of domestic cats were ubiquitous in ancient Egyptian culture, imbued with religious and mystical meaning. Cats are ubiquitous in modern media as well, although mostly, it seems, for the simple reason that we find these animals funny.

Whatever its meaning and significance, all domestic animals share the common feature that they are distinct from their wild ancestors in that they have a mutual relationship with humans so intertwined they have, other successive generations, become different species entirely. A dog is not a wolf, nor is a cat a lion. Try jumping on the back of a zebra uninvited and you’re likely to arrive in hospital.

Wild animals do not have the same relationships with humans as domestic animals do, whose evolution has been directly shaped by humans as far back as about 15,000 years.

But whilst visible and behavioral differences between wild and domestic animals are the most obvious expression of their genetic differences, a much less visible but more surprising change may be the first to take place in early domestication of species: their gut bacteria.

A team of researchers led by Lara Puetz and M. Thomas Gilbert at the Center for Evolutionary Hologenomics at the GLOBE Institute, University of Copenhagen, hypothesized that the gut microbiota may cause one of the earliest phenotypes — that is, observable characteristics, including behavior, regulated by genes — to change as wild animals are domesticated, and carried out experiments to back this up.

Publishing in Advanced Genetics, the team compared the gut microbiome of two lines of red junglefowl — the ancestors of domestic chickens — which were bred solely for either high or low fear of humans over eight generations. The link between fear and the gut microbiome has only been investigated recently, and since a key feature of domestic animals is their lack of fear of humans compared to their wild counterparts, Puetz and her colleagues wanted to see — in terms of their gut microbiome — exactly how early on this change from a feeling of fear to a feeling of safety in the presence of humans occurs.

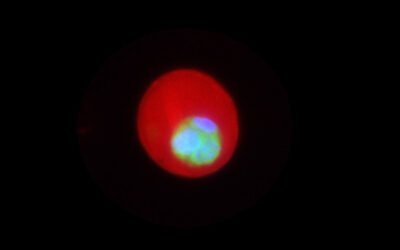

Using a technique called genome-resolved metagenomics, the team found a marked difference in neuroactive metabolites associated with fear conditioning between the two groups of birds.

Two main bacteria groups of interest were Lactobacillales and Clostridiales, and it was found that the low-fear group of junglefowl had low levels of the former and high levels of the latter in their gut bacteria. The latter, Clostridiales, has been previously associated with reduced stress in Japanese quail, and it is believed that this family of bacteria can be responsible for promoting biosynthesis of seratonin, which has been found in higher levels in low-fear red junglefowl males.

With domestication comes control, and a significant control imposed upon domestic animals is their diet. It is therefore perhaps easy to think that the domesticated junglefowl were eating differently to their wild counterparts, and therefore the change in gut bacteria is a product of diet. However, in this study, both groups of junglefowl were reared in identical environments, including what they ate. Therefore the authors rule out dietary change as a driver for changes in the gut microbiome.

However, the authors stress that their findings do not suggest a definitive causative role of gut bacteria on fear during domestication, rather that their findings can be a starting point for further studies. Having ruled out dietary changes as a driver for the differences in the low- and high-fear groups, they also acknowledge that host genetics also play a role in the make-up of their gut microbiome.

They therefore conclude that the phenotype selected for in these red junglefowl could reflect a convergence of various factors including microbial, but also those the host and its environment.

Reference: Lara C. Puetz et al., Gut Microbiota Linked with Reduced Fear of Humans in Red Junglefowl Has Implications for Early Domestication, Advanced Genetics (2021) DOI: 10.1002/ggn2.202100018