Nicole Steinmetz, professor of nanoengineering at the University of California San Diego, has been working on immunotherapies based on plant virus platforms for the past 15 years. She hopes that one day her team might develop a well-tolerated immunotherapy against metastatic cancers — those that spread to different regions of the body — to reduce if not completely eliminate the need for chemotherapy or radiation.

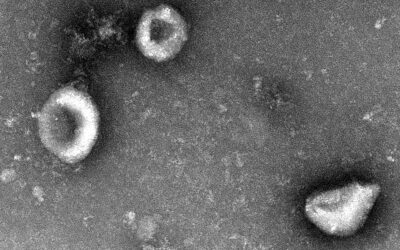

In a step toward this, her team has previously reported how a virus that infects black-eyed peas, known as the cowpea mosaic virus, can be designed to home in on the lungs, where it activates the body’s immune system to prevent and treat metastasizing cancer. “While non-infectious in mammals, it is recognized as foreign and stimulates an innate immune response through the activation of pattern recognition receptors,” wrote the team.

Now, in a follow up study published in Advanced Science, the researchers were able to take their cowpea-based immunotherapy one step closer to a potential clinical application.

Using unmodified cowpea viruses that are no longer restricted to the lungs and no longer require direct injection into tumors, the team showed the effectiveness of their approach in preventing metastasis from several new types of cancers including colon, ovarian, melanoma, and breast cancer.

“[The follow up study] provides a comprehensive approach to assessing new cancer treatments, while also highlighting the necessity of early diagnostic tools,” said Rob Swanda, staff engineer at the medical device company Becton Dickinson, who was not involved in the study.

Boosting the body’s self defense

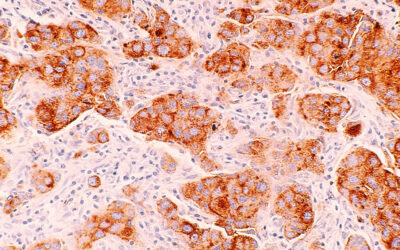

Metastatic cancers present a challenge as the patient’s immune system struggles to recognize cancerous cells as foreign invaders, allowing the metastases to proliferate and spread throughout the body unchecked.

The current gold standard in treating metastasizing cancer post-surgery is still based on chemotherapy drugs that, while effective, cause severe side effects. In search of less aggressive treatment alternatives, immunotherapies that harness the body’s own immune cells to fight off the cancer are gaining traction.

One promising immunotherapeutic approach makes use of modified human viruses, such as the herpes viruses and adenoviruses, known broadly as oncolytic viruses. They are manipulated to prevent infection and instead, specifically target cancer cells. As these cells are dying, they release cancer-related molecules that then stimulate an immune response against any remaining cancer cells.

Even though oncolytic viruses are designed not to infect healthy cells, there is still the risk of off-target effects, cautioned Steinmetz. “Many must be stored in ultralow freezers and require special handling; repeated treatment may lead to development of antibody drug resistance,” she added.

This is why for their immunotherapy, the team turned to cowpea viruses, which cannot infect human cells, whether healthy or cancerous.

A systemic approach

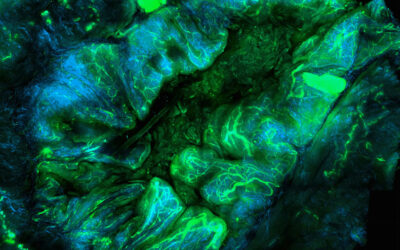

In previous work the team showed that when injected close to tumor sites, the viral particles are recognized by the immune system as foreign materials and begin recruiting more immune cells to the area where they are more likely to come across the cancerous cells and destroy them.

“The present work opens new opportunities to administer the particles systemically — so there is no longer the requirement of an injectable tumor,” said Steinmetz. “[The cowpea virus] targets immune cells and not cancer cells; it naturally interfaces with immune cells and ‘wakes them up’ to restore normal immune function and treat or prevent metastasis.”

Her team demonstrated that, similar to their previous strategy, immune cells activated by unmodified cowpea viruses were able to target developing tumor cells two weeks after injection.

“We wanted to create a prophylactic approach we could utilize for [different] tumors,” said Eric Chung, first author of the study. “In terms of manufacturing and production costs this approach is significantly cheaper [as opposed to traditional targeted nanoparticles] as we would only need to purify the virus and no longer would require the conjugation of a targeting peptide.”

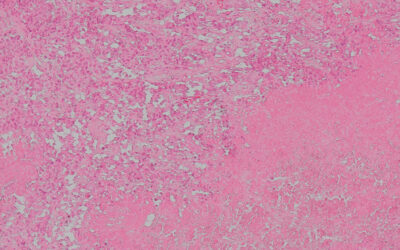

Mice remain cancer free, more tests needed

In mice treated with the immunotherapy, more than half survived, even when new tumor cells were reintroduced after 40 days, while all untreated mice succumbed to the disease. Similarly, administering the viral particles after surgically removing tumors also prevented metastasis in all disease models tested.

“Future studies could elucidate whether tumor protection could be extended further following multiple injections,” wrote the team in their paper.

Before the treatment can proceed to clinical trials, however, Swanda said more studies on other animal models are required to ensure safety. The viral dosage as well as appropriate routes of administration are further parameters that need to be clarified.

“Would it only be used for early diagnoses, or could it be extended to a broader range of patients? This is an exciting space that I look forward to learning more about,” Swanda said.

Steinmetz and her team say they will continue to decipher how the cowpea virus is stimulating the body’s own defenses, working toward their vision of an easy-to-produce, safe, and effective immunotherapy against metastatic cancers.

Reference: Young Hun Chung, et al,. Systemic Administration of Cowpea Mosaic Virus Demonstrates Broad Protection Against Metastatic Cancers, Advanced Science (2024). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202308237

Feature image credit: David Baillot/UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering

The feature image of this article was modified on April 2, 2024