Large infrastructure projects are often controversial. They are costly, they take years to plan and complete, and they may have a range of environmental and social impacts, which are often initially underestimated or downplayed. Yet they are also popular with politicians hoping to leave a legacy, a visible and tangible marker of success, ideally with long-term benefits for their constituencies.

Large dams might be considered a prime example of such controversies, where different interests, values, and visions of development clash. On the one hand, they have caused the displacement of millions of mostly rural people whose communities have been submerged by dam reservoirs, have affected the livelihoods of an even larger number of people downstream who depend on natural flood cycles for agriculture and fishing, and changed river ecosystems, often irreversibly so.

On the other hand, dams continue to be seen as a powerful development option in the context of accelerating climate change and renewed calls for economic development and electrification of countries primarily in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Balkans.

-

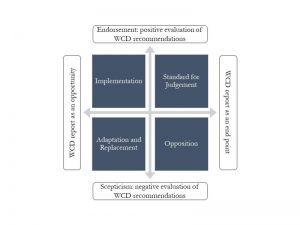

The World Commission on Dams’ (WCD) final report was published in 2000, containing research findings and recommendations regarding the planning, construction, and management of large dams. This figure summarises some of the suggestions for follow-up strategies and typical responses to the report made by researchers and stakeholders in the last twenty years. Where some called for literal implementation of WCD recommendations or used it as a standard for judgement of dam projects, others opposed the WCD’s work or saw it as an opportunity to propose new methods and procedures, effectively replacing it.

Twenty years ago, the World Commission on Dams (WCD) was established, following the initiative of the World Bank and the World Conservation Union (IUCN) to “solve” these controversies. Conflicts around dams had been particularly severe in the 1990s, with an alliance of NGOs calling for a complete halt of World Bank-funded dam construction in the 1994 Manibeli Declaration. The World Bank withdrew from the large Sardar Sarovar dam project on the Indian Narmada River, following public protests and an independent review of its environmental and resettlement impacts.

The idea behind the WCD was simple: to review what was known about large dams, and to assess how effective dams were at delivering what they promised. The WCD was composed of 12 Commissioners who represented different positions towards dams (pro-dam; anti-dam; neutral), stakeholder groups (academics; civil society; industry; government), and came from different regions of the world. It was chaired by Professor Kader Asmal of South Africa, a former Minister of Water Affairs and Forestry, who had the support of a dedicated Secretariat in Cape Town, and was overseen by a 68 member Stakeholder Forum representing all sorts of interests in dams.

The WCD, which was active between 1998 and 2000, commissioned the largest review of research on dams and compiled a number of recommendations that were meant to be taken up by governments and policy-makers. These had a particular emphasis on reducing social and environmental impacts of dams, assessing dams alongside their alternatives, and turning “losers” into beneficiaries.

Twenty years on, it is worth asking; what has changed? What can we learn from the experience of WCD? Was it worth the effort? Looking at these long-term impacts of a global environmental commission seems timely because more and more environmental issues are being addressed at a global level today, with the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) being the latest example.

Thus, in their WIREs Water review, Christopher Schulz and Bill Adams provide an overview of the responses to the WCD’s work. To its supporters, it may come as a relief that yes, it did have an impact. For example, researchers have developed novel methodologies to implement some of the recommendations to improve decision-making around dam construction.

Others continue to use the authority of the WCD’s report to give weight to their calls for addressing social and environmental impacts of dams. The dam industry worked with some NGOs and governments to develop a “Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol” to provide concrete guidelines for building less impactful dams, although its critics argue that it is not being taken up widely enough. That said, the WCD has also sparked some angry responses, among those who felt it infringed on developing countries’ governments’ autonomy to take decisions on dam construction, and those who considered that it was too anti-dam. But even such negative responses are evidence of the WCD’s impact. Twenty years later, its work has not been forgotten, even if progress towards “better” decisions around dams might feel painfully slow.