In recent years, retinal prostheses for the blind have moved beyond the pages of science fiction and are now a real possibility. The current generation of retinal stimulators, however, uses metallic tracks to address individual electrodes from the driving circuitry. This leads to severe limitations on the scalability of electrode density and numbers, and subsequently to reduced efficacy of the retinal stimulators.

More recently the development of an optically driven retinal stimulator has made it possible to address the individual electrodes using light. This has paved the way for implants with a large number of closely packed electrodes, but at the expense of limited stimulation functionalities. If the quality of vision delivered by such devices is to improve, new fabrication strategies and technologies enabling many more electrodes and a high degree of stimulation flexibility must be developed.

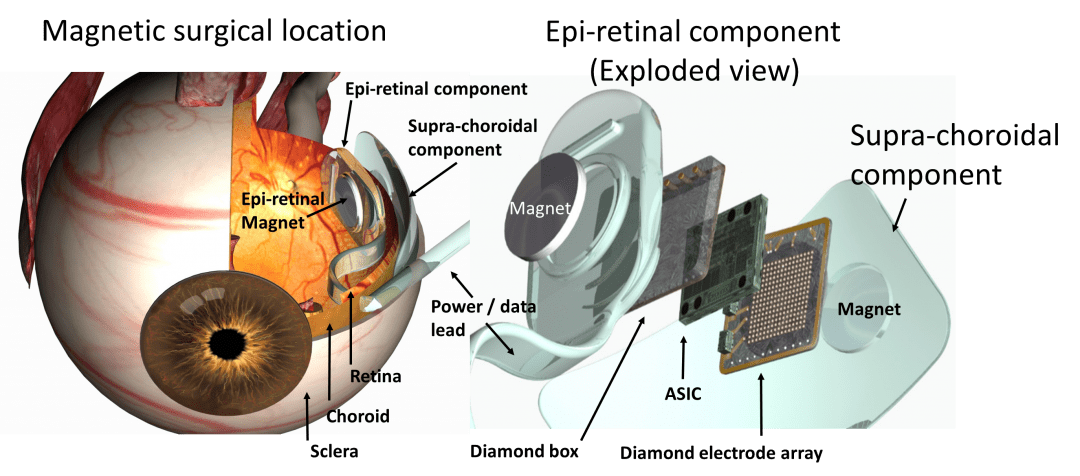

With this in mind, a multidisciplinary team of scientists from the schools of Physics, Electrical & Electronic Engineering, and Anatomy and Neuroscience from the University of Melbourne, together with researchers from RMIT and the Australian College of Optometry have recently developed a diamond retinal prosthesis with 256 electrodes separated by 150 µm integrated with a microcontroller permitting electrode by electrode control. Using diamond for the electrode array and encapsulation technology, they achieved a self-contained diamond implant which addresses both scalability and stimulation functionalities needed for prosthetic vision. Moreover, diamond is a biostable and biocompatible material, which supports the longevity of the implant.

The device provides an unprecedented level of flexibility in stimulation strategy and is an ideal platform with which to establish the limits of acuity achievable by electrical stimulation of the retina, thereby bringing us one step closer to the day that such devices can be offered to visually impaired patients.

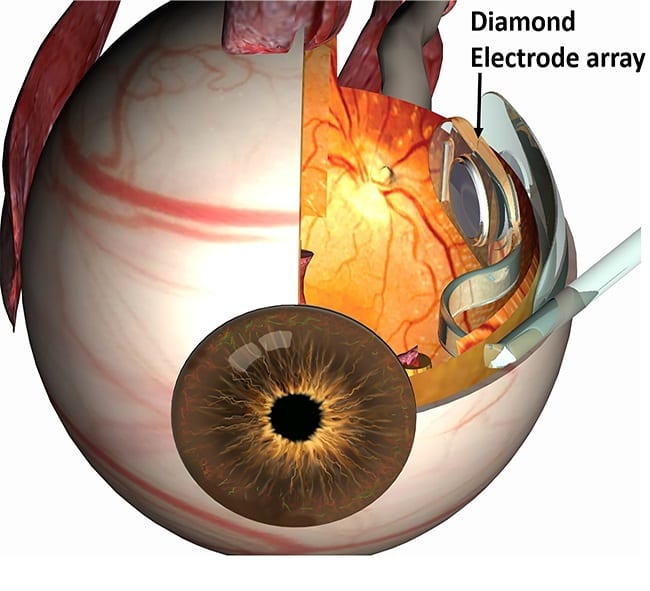

Surgical location of the suprachoroidal components (between sclera and choroid) and the epiretinal components of the retinal prosthesis.