Image credit: Testalize.me on Unsplash

The discovery of CRISPR enzymes isolated from bacteria has not only transformed our ability to edit the genome and therefore treat a number of genetic disorders, but has also opened the door to enhanced diagnostic testing.

Nucleic acid tests detect genetic information such as DNA and RNA, and are often used in the identification of viruses or bacteria. They are currently being widely used in the detection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus — for which there has been an unprecedented demand in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic — with the LMAP (loop-mediated isothermal amplification) test being one of the most common.

CRISPR-based nucleic acid assays are faster, more reliable, specific, and cheaper in comparison, and have already found application in the detection of the Dengue virus (DENV), human papillomavirus (HPV), and Zika virus (ZIKV).

Yet their lack of digitization has hindered them, says a team of scientists led by Professor Jeff Wang from Johns Hopkins University. “All CRISPR-based assays to date are performed in reaction tubes or reaction wells,” said Wang. “This reaction format has two shortcomings: the viral load in a sample is difficult to quantify because it is only loosely related the signal intensity, [and] samples with low viral loads require longer time to produce a detectable signal.”

Digital detection is also a powerful and reliable tool that enhanced the diagnostic capabilities of tests such as PCR and LAMP, yet no digital enhancement has been realized for their CRISPR-based counterparts.

Creating a sensitive, digital CRISPR assay

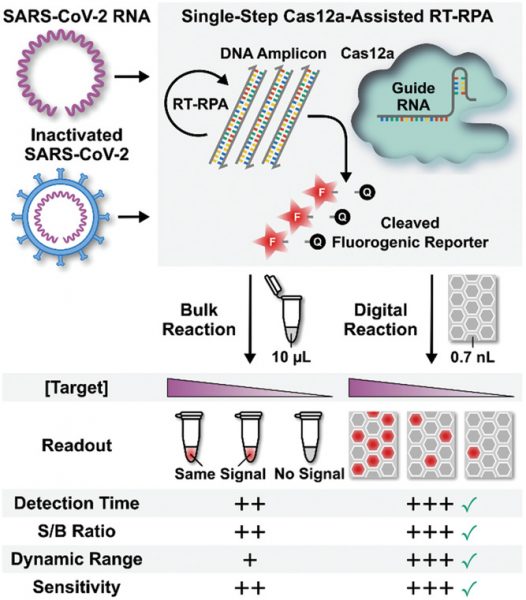

To solve this problem, the team developed an assay they call deCOViD (digitization‐enhanced CRISPR/Cas‐assisted one‐pot virus detection), which is the first digital CRISPR/Cas‐assisted assay that can detect SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA and heat‐inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 in a single step. Their results were recently published in Advanced Science.

“Our digital CRISPR-based assay can count individual viruses in a sample,” said Wang. “It also maintains a constantly rapid assay time for samples with both high and low viral loads.”

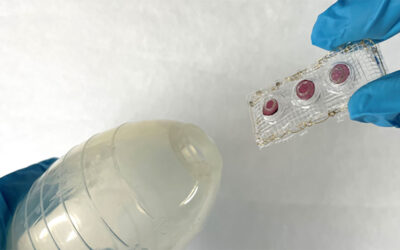

The assay uses fluorescent signalling to detect the presence or absence of the virus — it integrates transcription and amplification of viral RNA into one step and then these RNA fragments activate RNA-guided CRISPR complexes to trigger fluorescence in positive samples.

“Detecting SARS-CoV-2 virus in a sample is like the proverbial problem of finding a needle in a haystack,” explained Wang. “Imagine that even if the needle can make copies of itself, it can still take a long time to make enough copies of needles and become visible in the haystack. But if the haystack is first divided into many smaller piles and the needle is in one of the smaller hay piles, then the needle needs to make less copies of itself to be visible enough in the smaller piles thereby it will take shorter time to be detected. We used the same strategy. When we divide our assay and SARS-CoV-2 viruses into 20000 tiny wells, each virus in its tiny well can be detected faster and at the same time as viruses in other wells.”

To test the feasibility of deCOViD in clinical testing, the researchers tested four samples obtained from nasal swabs, which included two SARS‐CoV‐2 positive samples, one SARS‐CoV‐2 negative sample, and one influenza sample, and compared it against a conventional, multi-step CRISPR-based assay they termed a “bulk assay”. To confirm the results, all tests were run against a standard PCR assay.

“Both the bulk assay and deCOViD yielded higher signals from the two positive samples than those from the negative sample — indicating successful detection results that agree with RT‐qPCR,” wrote the authors. “In addition, for the influenza sample, both the bulk assay and deCOViD yielded signals that are indistinguishable from those from the negative sample, which matches RT‐qPCR while also illustrating the specificity of both methods.”

In a final test, the team diluted their nasal samples by two-fold and found the virus became undetectable to the bulk assay but was successfully detected by deCOViD. This is because RNA amplification and sampling is carried out in digital reaction wells, where every copy of the target is isolated at a locally elevated concentration, facilitating rapid amplification that is independent of the initial sample’s concentration. This not only provides a more sensitive test, but enhances detection time.

When will they be used on the front lines?

“Our work so far has been an academic pursuit, but we are certainly interested in commercializing our assay and contributing to mass screening and testing for SARS-CoV-2 in the near future,” added Wang. “It is expected that several improvements in user-friendliness can facilitate the commercialization of our work, which include simplification of fluorescence detection of digital chip and automation of sample loading process.”

Assay components can also be further optimized to detect SARS-CoV-2 even faster and directly from different samples such as saliva, he continued. Fluorescence detection can can also be simplified by either using a commercialized chip reader that is compatible with the digital chip or by implementing a mobile phone-based fluorescence detection system.

“As deCOViD can be readily designed for other DNA or RNA targets, we foresee applying it toward other diseases,” the team wrote in their paper. “Based on the encouraging results and potential for improvement, we believe deCOViD can open a new avenue for advancing CRISPR/Cas‐assisted diagnostic assays and provide a new tool for combating the COVID‐19 pandemic and beyond.”

Reference: Joon Soo Park, et al., Digital CRISPR/Cas‐Assisted Assay for Rapid and Sensitive Detection of SARS‐CoV‐2, Advanced Science (2020). DOI: advs.202003564