Endometriosis is a devastating disease that affects roughly 176 million women worldwide. In individuals with the disorder, tissue that is similar to the inner lining of the uterus called the endometrium produces lesions which spread outside the uterus, causing agonizing symptoms, including chronic pelvic pain and infertility that are often difficult to diagnose.

“It can be very difficult to diagnose because there are no unique clinical [features],” said Dan Martin, a retired medical practitioner and scientific and medical director of the Endometriosis Foundation of America (EndoFound). “It can look like a lot of other diseases, such as complications of pregnancy, STIs, bladder infection, irritable bowel, kidney stones, and many others. And in spite of a 10% lifetime prevalence, primary care practices might encounter 0.2% new patient cases per year.

“There is also an issue of normalizing pain in women,” he continued. “A study done in the UK found that over half of its participants were told there was nothing wrong with them, and when the primary care giver did believe them, half the time they didn’t recognize the patient’s symptoms as gynecological and sent them to a non-gynecological specialist.”

Research funding in this area is also generally limited. For benign diseases, in 2021 609 grant applications were submitted to the US Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program across 42 categories, and only 98 were approved. Of the 609, only six were related to endometriosis, and none of those were approved.

But endometriosis is a critical health care issue for women, affecting approximately 10% of reproductive-age women. Despite progress in medical treatments developed for endometriosis-related pain, there are currently few effective treatment options for suffering women.

“Current medical therapies result in infertility, and patients wishing to improve fertility often seek surgical removal of the lesions,” explained Ov Slayden, professor at Oregon Health and Science University, in an email. “Unfortunately, the recurrence rate after surgery is high, with >27% of patients requiring three or more surgeries.”

Slayden is part of a team of researchers, which includes Oleh Taratula, professor at Oregon State University, who are seeking to develop a safe, non-surgical means of removing lesions. To do this, they turned to a therapy previously applied to treating cancer known as magnetic hyperthermia where under an alternating magnetic field, nanoparticles generate heat to kill cancerous tissue.

Limitations in the technology hindered the team from directly applying it to treat endometriosis in their proof-of-concept study. For one, therapeutic temperatures can only be achieved by injecting the conventional nanoparticles directly into the affected cancerous tissue, making deep-seated tumors and widespread internal lesions difficult to treat with this method.

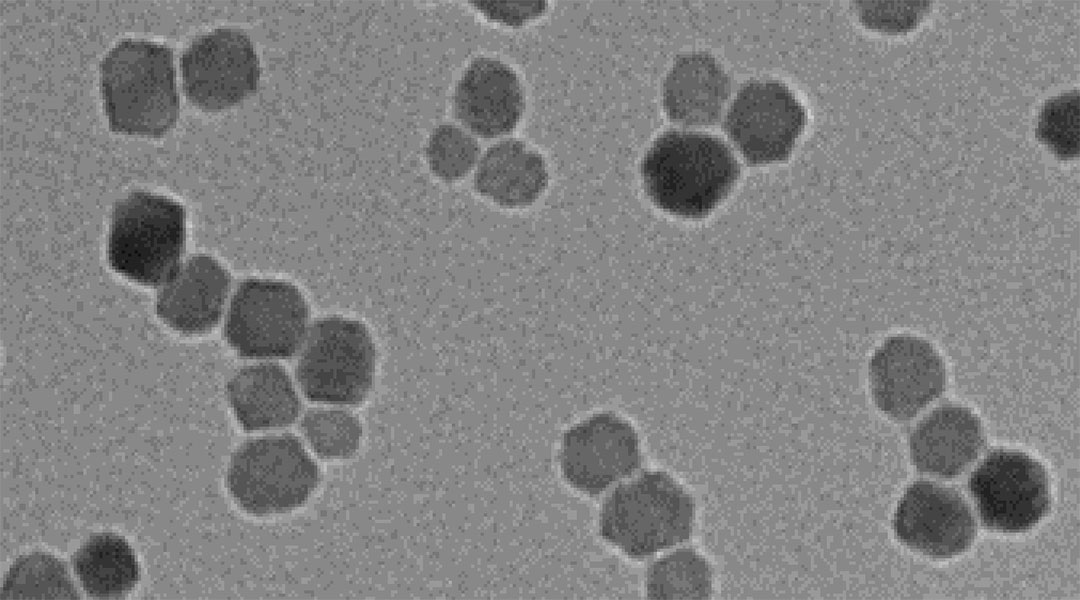

“Due to this significant limitation, magnetic hyperthermia has not been investigated for other diseases associated with widespread lesions, including endometriosis,” said Taratula. “To solve this problem, we invented targeted nanoparticles with high heating efficiency that accumulate in endometriosis lesions.”

The idea emanated from previous work done by the group, which demonstrated that nanoparticles naturally accumulate in endometriotic lesions after systemic injection. Like cancer, endometriosis is an angiogenesis-dependent disease, meaning its progression relies on the formation of new blood vessels. Circulating nanoparticles are taken up by blood vessels, brought to the endometriotic lesions, and extruded into the surrounding tissue.

To enhance the accumulation of the nanoparticles in endometriotic tissue, the team added peptides to their surface that target the cell surface receptor, VEGFR-2, also known as kinase insert domain receptor or KDR, found in abundance in endometriotic cells.

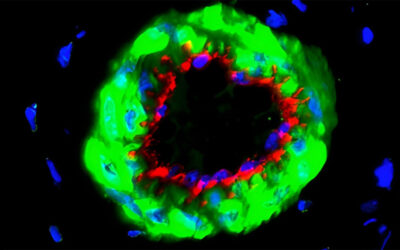

“Studies in mice bearing […] endometriotic lesions revealed that our new nanoparticles accumulate specifically in the endometriotic grafts following intravenous injection at a low clinical dose, selectively elevating the temperature inside of grafts above 50°C, and completely eradicating the grafted tissue after a single 20-minute session,” said Taratula.

The team also demonstrated their nanoparticles’ ability to behave as MRI contrast agents to detect lesions before treatment. In a mouse model, after injection the nanoparticles were visible at lesion sites.

“This study blends into a problem that a lot of research in endometriosis has, and that is getting around the need for surgical diagnosis,” explained Martin, who was not involved in the study. “MRIs, in general, are good at picking up and filtering endometriosis, but it’s difficult to pick up anything less than 5cm in size.

“If this is true, then this therapy will be useful for cases with large lesions, and if the nanoparticles can target VEGFR-2/KDR, it will make it easier to see which lesions are actually endometriosis,” he added. “This approach may be best for patients with pain and deep endometriosis, but they will need to prove this in large animals for this to be of clinical significance.”

Slayden disclosed that the team plan to continue validating their therapy further. “Our estimate is that proof of concept work will be completed within the next year and follow-up with the FDA over the next 3-5 years,” he said. “We have identified clinical partners for phase 1 studies once approval is in place.”

Reference: Youngrong Park, et al., Targeted Nanoparticles with High Heating Efficiency for the Treatment of Endometriosis with Systemically Delivered Magnetic Hyperthermia, Small (2022). DOI: 10.1002/smll.202107808