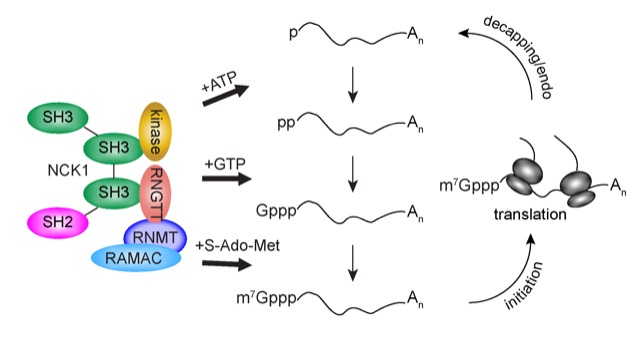

The genetic information for making every protein is transferred from DNA to the cytoplasmic protein synthesis machinery by an intermediary molecule termed messenger RNA, or mRNA. Cells have many different kinds of RNA, and mRNA is differentiated from others by a ‘cap’ consisting of a single modified guanosine (G) nucleotide that is added onto the very end while the mRNA is being made in the nucleus.

The cap is bound by a number of different proteins that are important for gene expression. Some of these guide additional steps in mRNA processing, others are responsible for initiating the synthesis of proteins from the information in the mRNA, and a number of proteins act to remove the cap from mRNA. It is generally thought that this process of ‘decapping’ terminates the translation of genetic information in mRNA into proteins and leads to the degradation of mRNA in the cytoplasm.

However, research over the past decade has demonstrated a more complex picture. As detailed in a WIRES RNA review article by Trotman and Schoenberg, mammalian cells are capable of recapping mRNAs that have lost their caps. Cyclic decapping and recapping, or ‘cap homeostasis,’ is proposed as a way that cells can temporally control protein production for particular genes. The recapping of mRNAs missing portions of their 5’ ends diversifies the population of mRNAs present within the cell and may lead to the production of shortened proteins with altered function. mRNA recapping has also been observed in fruit flies as well as distantly related eukaryotes called trypanosomes, raising important questions about the evolution of this gene regulatory process.

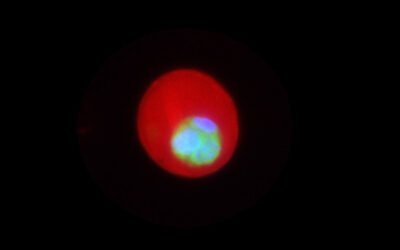

Kindly contributed by the Authors.