On a single weekend earlier this year, 3500 people swimming off the coast of Australia were stung by jellyfish. This rather dramatic event is part of a decades long global trend: jellyfish blooms are increasing in size and regularity.

These blooms can have a massive impact on the ecology and economy of the affected area. In 2007, a jellyfish bloom caused the deaths of $2 million worth of farmed salmon in Northern Ireland. Regular blooms off the coast of Japan have devastated local fish populations, and in 2009 caused a fishing trawler to capsize.

If jellyfish could be turned into a commodity, then perhaps farming might restrict the uncontrolled growth of these blooms. There is a market for jellyfish as food in Southeast Asia, but with a yearly harvest of around 400 tons, it barely makes a dint in the overpopulation situation.

What if jellyfish could be used to make plastic? Not only might this create a market for farming, it could help supplant fossil fuels as a feed-stock for plastic production.

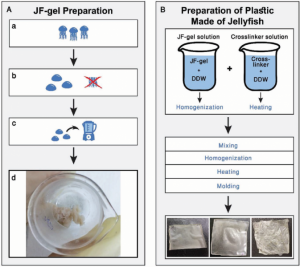

The fabrication process.

An Israeli team recently set out to investigate this question. The fabrication process was quite straightforward (see above). The jellyfish were collected from the Mediterranean Sea. They were cleaned, their tentacles removed, and then blended with a chemical called alginate. The process ended with a heating and molding step.

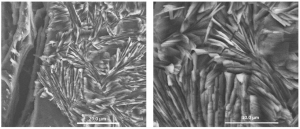

The new material was examined using scanning electron microscopy (see below), which showed that the plastic was composed of an unusual “pseudospherulite” structure. This structure is believed to confer strength on the bulk material. It was also found that the new plastic showed better heat tolerance than other comparable plastics.

While more work needs to be done, the team hope that these promising results may lead to applications in packaging and biodevices.

SEM images of the jellyfish plastic.