For David Polgreen, the past 35 years have been a relentless battle against chronic fatigue syndrome, a condition he developed following a university holiday he took with a friend back in 1988.

“When we got back, neither one of us felt great, and through that term I could just never recover,” he explained in a conversation over Zoom. “I played tennis for the university, or I was trying to. I finished the term and it all got steadily worse and worse. I just felt like someone had pulled the plug out from my energy, I couldn’t even lift my limbs.”

Formally known as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), this condition is generally characterized by persistent and unexplained fatigue though it also presents a myriad of symptoms that can vary between patients and fluctuates over time.

“When people say its tiredness, it’s not tiredness like, ‘Oh, I’m ready for bed’,” continued Polgreen, an active member of the Oxfordshire ME Group for Action (OMEGA). “It’s exhaustion, it’s a lack of energy, it’s absolutely heavy, and you’re just not able to do anything.”

When we spoke with other members of the OMEGA organization, they shared similar ordeals. “It’s incredibly debilitating and frustrating,” said James Charleson, a patient with ME/CFS who got in touch with us through OMEGA via email. “I used to be very physically and mentally active and now I have to be very prudent with how I expend physical and mental energy.

“In a typical day, I have to spend at least 50% of my waking hours lying down, resting. The grogginess and brain fog mean that days often pass me by without me really being aware of it.”

The experiences of individuals like Polgreen and Charleston highlight the deep impact that chronic fatigue syndrome has on the lives of those affected by this debilitating disorder. One of the greatest challenges is the fact that no definitive diagnostic tests or treatment options exist.

“Having something that nobody can put a finger on, something nebulous, something people don’t understand is distressing,” said Polgreen. “I’d just rather know than live with uncertainty.”

But now, there is hope that this could one day change with news of a new diagnostic test that can, for the first time, accurately identify hallmarks of chronic fatigue syndrome in blood cells. The study was published by researchers at the University of Oxford led by Karl Morten and Wei Huang who have reported their findings in Advanced Science. The test has an accuracy rate of 91%, and could be a much-needed beacon of hope for many.

What a diagnostic test would mean

In the absence of a precise diagnostic test, many people with chronic fatigue syndrome are forced to rely on subjective assessments and the process of elimination in order to receive a diagnosis — or in some cases, they don’t receive a clear diagnosis at all.

As a result, patients find themselves navigating their illness without a clear understanding of what is happening to them. “It is a common occurrence for undiagnosed people with ME/CFS to continue to fight the fatigue, and so their condition worsens over time,” explained Charleston. “Pacing and managing energy levels are critical to prevent the worsening of ME/CFS.”

Historically, those suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome have encountered significant challenges in gaining recognition and validation within the medical community. Polgreen said he was lucky to have had a family doctor who took him seriously. He was sent to a specialist who, through a painstaking process of elimination, diagnosed him with chronic fatigue syndrome. But a common experience among patients with ME/CFS is an uphill battle and a long road to diagnosis.

“It took over a decade before I was finally diagnosed with ME/CFS,” said Charleston. “Initially, I only had mild symptoms; I was often tired and would sometimes crash with fatigue, but I put this down to being a teenager and to not sleeping very well. I kept on pushing myself through the fatigue and my condition worsened over the years.”

ME/CFS also makes the prospect of maintaining gainful employment an insurmountable challenge, and an added difficulty in not having a clear diagnosis surfaces when applying for welfare. “A lot of people face huge hurdles to get [welfare],” explained Polgreen. “And a lot of people end up living in relative penury. Having a diagnosis means all that becomes easier.”

Slow to catch up, but things are changing

Jonas Bergquist, an M.D./Ph.D., director of the ME/CFS Research Centre, and professor in analytical chemistry and neurochemistry in the Department of Chemistry at the Biomedical Centre, Uppsala University, Sweden, who was not involved in the study, has been studying molecular diagnostics in the context of neurological and inflammatory diseases, such as ME/CFS, for the last several decades.

While he acknowledges the slow pace at which the medical community has caught up with the disease, he emphasized that its complexity is what makes it not only difficult to diagnose but also to develop a general diagnostic test.

“One of the difficulties is the complexity of the disease because it’s a multi-organ disorder, you get symptoms from many different regions of the body with different onsets, though it’s common with post viral syndrome to have different overlapping [symptoms] that disguise the diagnosis,” he said.

A positive shift has been unfolding in recent years, with some experts crediting the COVID-19 pandemic and the rising prevalence of long COVID cases as a reason for raised awareness about chronic fatigue syndrome and related conditions.

“In the last ten years, I think there’s been a dramatic change, and acceptance has really improved,” said Bergquist. “For years I’ve been working quite intensely with patients who have post-viral issues, including ME/CFS.”

“The pandemic itself has also made more people aware that this kind of phenomena can exist,” he continued. “If you consider multiple sclerosis (MS), which is rather well known, ME/CFS is twice as common. It therefore should be better known, but it’s not. That has changed a lot now.”

Though this field of research remains relatively small, an increasing number of scientists are taking on the challenge of expanding our understanding of the biological underpinnings of this condition and developing better means of identifying it.

A test based on single cell Raman spectroscopy

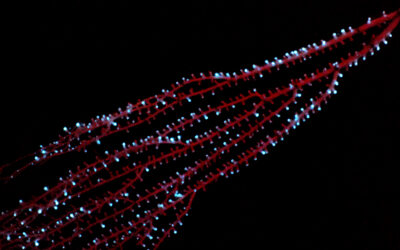

The study by Karl Morten and Wei Huang, whose research group is one of the few looking to provide a solution to this long-standing problem, reports a Raman-based test that characterizes features of blood cells known as peripheral blood mononuclear cells, or PBMCs, that are unique to those suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome.

Raman spectroscopy is a classic technique used by chemists to determine the structure of a molecule based on the way light interacts with its atoms and chemical bonds. When applied in biology, it has been used to determine the characteristics of single cells.

When a laser beam is directed at a cell, some of the scattered photons undergo shifts in energy due to interactions with the cell’s molecular constituents. These energy shifts, or Raman shifts, are characteristic of specific chemical bonds and molecular structures, allowing researchers to obtain a molecular fingerprint of the cell.

Previous studies have identified PBMCs in ME/CFS patients as exhibiting reduced energetic function compared to healthy controls. With this evidence, the team hypothesized that single-cell analysis of PBMCs might reveal differences in the structure and morphology in ME/CFS patients compared to healthy controls and other disease groups.

“Single cell Raman spectral profiles are complicated, with around 1500 individual signatures,” explained Morten. “These signatures are complex and by eye there are not necessarily clear features that separate ME/CFS patients from other groups.”

However, this becomes simpler with the help of artificial intelligence. “We used an approach called ‘ensemble learning’, in which individual machine learning models were combined to yield a more powerful one,” explained Jiabao Xu, the study’s lead author. “Each individual model was not able to generate high accuracy, but ensemble learning takes the advantages and strengths from individual models.”

“The AI looks at this data and attempts to find features which can separate the groups,” added Morten. “Different AI methods find different features in the data. Individually, each method is not that successful at assigning an unknown sample to the correct group. However, when we combine the different methods, we produce a model which can assign the subjects to the different groups very accurately.”

Incredible accuracy

This work builds on a previous pilot study published by the group which evaluated small biological entities collected from severe ME/CFS patients called extracellular vesicles that shuttle biological materials between cells. “When Raman was added to a panel of potentially diagnostic outputs, we improved the ability of the model to identify the ME/CFS patients and controls,” said Morten.

The current study included 98 participants, including 61 ME/CFS patients of varying disease severity and 37 healthy and disease controls. The team’s model was able to correctly identify patients with ME/CFS with a 91% accuracy. There is also hope that it could be used to diagnose other diseases for which the underlying mechanisms are still unclear.

“The timing is perfect as, although unfortunate, the emergence of long COVID lifts the research momentum and infrastructure around those unexplained post-infection chronic diseases, which all have very similar symptoms,” said Xu.

“We are looking to extend these studies into long COVID and chronic Lyme disease,” added Morten. “In the paper, multiple sclerosis (MS) samples could also be identified with high accuracy. It is possible the approach could result in early diagnosis in MS and perhaps other chronic conditions, like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“This could be a game changer as we are unsure what causes these conditions and diagnosis occurs perhaps ten to 20 years after the condition has started to develop. An early diagnosis might allow us to identify what is going wrong with the potential to fix it before the more long-term degenerative changes are observed. The triggers of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and MS are unlikely to still be present when the late stage pathology occurs.

“With an early diagnostic test potentially identifying new therapeutic areas, we could treat before the condition progresses to the point of no return.”

Challenges still ahead

Morten pointed out that the complicated nature of carrying out Raman analysis as well as preparing the cell samples is a limitation of the current test.

“Our paper is very much a starting point for future research,” said Morten. “Larger cohorts need to be studied, and if Raman proves useful, we need to think carefully about how a test might be developed. At over £200,000 [roughly US$250,000] for a state-of-the-art Raman microscope, a clinical test will likely have be developed incorporating Raman into a different device. This is very possible.”

Bergquist was in agreement: “[Raman] is very advanced, not necessarily something you would see in a doctor’s office. It requires a lot of advanced data analysis to use — I still see it as a research methodology. But in the long run, it could be developed into a tool that could be used in a more simplistic way.”

He also emphasized that what Morten and his colleagues have achieved represents a significant piece in the puzzle of ME/CFS. Their work not only offers patients a path to closure and a way to manage their symptoms, but also holds the potential to unveil crucial insights into the biological mechanisms underlying this condition.

Armed with this knowledge and a growing awareness of ME/CFS, researchers may one day be poised to develop effective treatments. However, for now, Morten and his colleagues remain dedicated to refining their test. In doing so, they’ve already instilled hope within an under-served community of individuals.

“This demonstrating of clear differences in the cell biology of people with ME/CFS and healthy controls will hopefully help to dispel the notion that ‘it’s all in our head’,” said Charleston.

Reference: Wei E. Huang, Karl J. Morten, et al., Developing a Blood Cell-Based Diagnostic Test for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Using Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells, Advanced Science (2023). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202302146

Feature image credit: Annie Spratt on Unsplash