Gaucher disease, a rare hereditary condition, is prevalent among the Ashkenazi Jewish population. The severity of this disease can range from milder forms that are treatable to others accompanied by extensive brain damage and death.

New findings based on zebrafish experiments indicate that the genetic variation responsible for Gaucher disease may have in the past provided protection from tuberculosis. The disease may have persevered in this Jewish population as a remnant of the times when tuberculosis ran rampant.

“Our work shows that it is possible that a mutation causing Gaucher disease might have been beneficial to this population when tuberculosis was a very common and often fatal illness,” said Laura Whitworth, a researcher at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. “If the benefit of surviving TB [tuberculosis] was great, that could outweigh the negative consequences of Gaucher disease symptoms.”

A rare disease

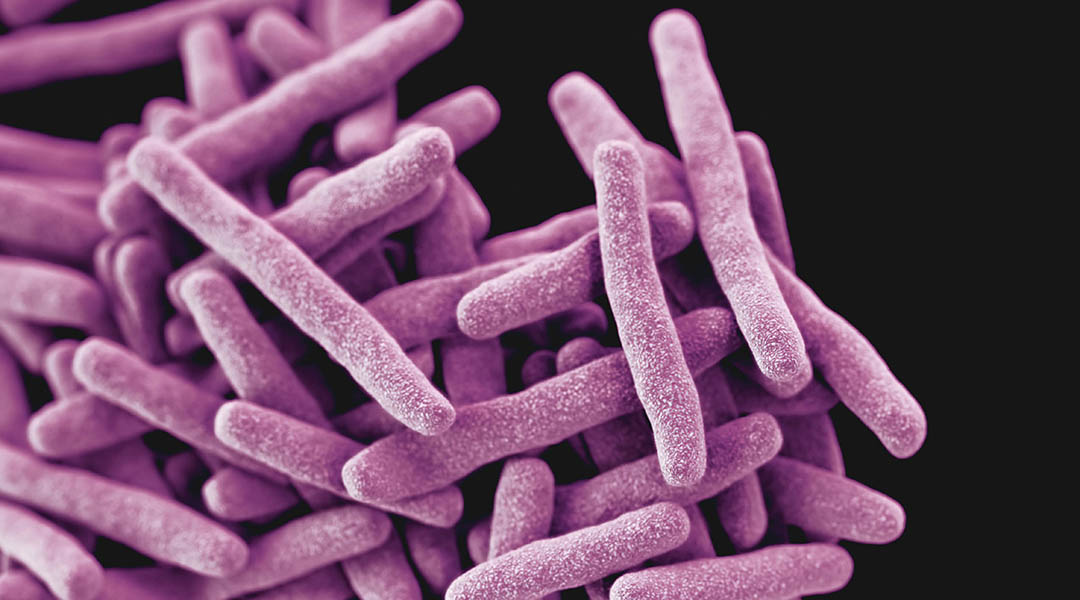

Whitworth works in the laboratory of Lalita Ramakrishnan where they study tuberculosis and what makes people more or less susceptible to it using zebrafish models. With their transparent bodies and susceptibility to Mycobacterium marium — a cousin of the bacteria that causes tuberculosis in humans — zebrafish make for wonderful models to study the disease as these small fish can be genetically manipulated and their immune systems act in ways similar to that of humans.

In earlier experiments, Ramakrishnan and colleagues found that a genetic mutation for another lysosomal storage disease made the zebrafish highly susceptible to tuberculosis bacteria. As the mutation is quite rare in humans, the research team turned their attention to a more common variant found in Gaucher disease.

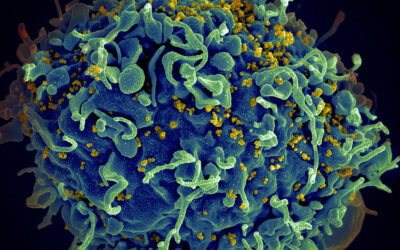

Gaucher disease is characterized by an abnormal buildup of fatty compounds in the cells of the liver, spleen, lungs, bone marrow, and the brain. At the cellular level, it is marked by the faulty behavior of macrophages, a type of immune cell. Always on the move, macrophages capture microbes and with the help of intracellular lysosomes, destroy them. Lysosomes rely on enzymes to break down fats and proteins, whose buildup may otherwise be toxic. Mutations that cause Gaucher disease affect the functioning of enzymes that break down lipids. As a result, the lyosomes become enlarged with fatty lipids, in turn, making macrophages sloth-like in their movements and functions.

People with a defective gene for an enzyme that metabolizes lipids experience Gaucher disease, with symptoms varying widely. A rare disorder, Gaucher disease is inherited in a recessive fashion, meaning an individual must carry two copies of the mutation. As a result, people who possess only one copy of the gene — and show no symptoms — are likely to be unaware of their carrier status. While the disease can be untreatable, enzyme replacement therapy in which the defective enzyme is delivered to the cells to help break down the lipids can help alleviate symptoms.

While Gaucher affects one in 40,000 to 60,000 people in the general population, it is much more prevalent in Jewish populations originating in Eastern and Central Europe. Among these, in Ashkenazi Jews, who make up 8 in 10 of the population, Gaucher disease may affect one in 800 births, which is some 50 to 75 times higher than the general population.

Gaucher disease and tuberculosis

In the laboratory, the researchers bred zebrafish with specific genetic mutations that cause Gaucher disease, leading to lipid accumulation inside macrophages. But exposure to the tuberculosis bacteria led to a surprising finding: Gaucher disease mutations made the zebrafish less susceptible to tuberculosis, not more. “We find that zebrafish carrying a mutated form of the gene which causes Gaucher disease in humans are resistant to TB bacteria, surprisingly,” said Ramakrishnan.

More experimentation revealed that the kind of lipid aggregating inside lysosomes, called glucosylsphingosine, acted like detergent, breaking through the bacteria’s cell membranes. “Our finding that the fatty chemical has broad bacterial killing activity by acting as a detergent suggests new approaches to treating TB as well as other hard to treat bacterial infections, particularly ones that are resistant to traditional antibiotics,” said Ramakrishnan.

The manifestation of Gaucher disease depends on an individual bearing two copies of the responsible mutant gene. So, people with a single copy of the mutation have just enough enzyme to break down lipids, and are susceptible to tuberculosis. Only those with both copies of the gene would have enough of the lipid buildup and benefit from its antimicrobial activity.

These results suggest that Gaucher disease may be a remnant of times when protection against tuberculosis may have been necessary. Additional support for this theory comes from experiments done in human macrophages. The recent preprint study reported finding that human macrophages with Gaucher disease mutations were protected against tuberculosis.

But researchers caution that their findings only highlight a potential reason for Gaucher mutations persisting in the Ashkenazi population. In order to establish whether these variants were historically prevalent, DNA analysis of ancient populations is needed.

Population bottlenecks could also have contributed to the prevalence of Gaucher disease in this Jewish population. For instance, fewer people with this mutation could have had an outsized effect in smaller populations that expanded.

“If the few individuals who survived the bottleneck were carriers of the allele, then it would have dramatically increased in frequency, regardless of its benefit under conditions of TB infection,” said Whitworth. “However, our findings suggest that alternatively or additionally, selection in the manner we describe may have played a role in the persistence of this mutation.”

Reference: Jingwen Fan, et al., Gaucher disease protects against tuberculosis, PNAS (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2217673120

Feature image credit: CDC on Unsplash