Wyatt Million was always interested in marine biology and wanted to work with dolphins. But after a visit to COP22 in Marrakech, Morocco in 2016, he became compelled to do something more impactful, which is why he picked corals. “I wanted to do something more for the environment and more for saving the oceans,” he said.

Today, he is a researcher at Justus Liebig University in Giessen in Germany, after having completed a Ph.D. studying coral at the University of Southern California.

In his latest paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, he has discovered that genetic variation is key to the success of transplanted coral reefs. Transplanting coral colonies is a common strategy for saving failing reefs.

However, up until now, there was no solid evidence as to which coral would thrive and where. It was known that some environments were generally better, and some individuals (in terms of their genes, i.e., some genotypes) were also more successful overall.

“But the most interesting aspect for this is that some individuals perform really well at some sites while some others perform better at other sites,” said Million. His team’s experiments revealed that the interaction between the environment and the genes is actually the key to success.

Building a diverse portfolio of corals

That is why they concluded that restoration initiatives should support genetic diversity: “Having a lot of individuals in your restoration stock [is important] so that you’re not relying on one coral to do all the growing, and it turns out it’s not going to do well everywhere,” Million added.

Study senior author Carly Kenkel from the University of Southern California compares it to investing: “You can put all your [funds] in the one, like, tech stock that you think is going to do really well […] but then something goes pear-shaped ― you’ve lost all your money.” Instead, with a diverse portfolio, “you’re investing in a whole lot of funds, maybe some do well, and some don’t but on average you’re beating the market”.

The team also found that coral are good at adapting to their environments — because adult coral cannot move, they cannot escape from an environment that becomes unfavourable, so adapting might prove advantageous. On the other hand, being able to change one’s traits in order to adapt might be energetically expensive, and, before the start of the experiment, the researchers didn’t know to what extent coral was able to change its traits.

In the end, they observed that corals that had more plasticity, in this sense, did tend to grow more and survive better across all the sites. “That’s really exciting on a lot of fronts ― it means that corals have this ability to potentially prolong their survival, their persistence under climate change,” Million said.

One advantage of studying coral is that it is easy to control for genetics: “You can basically clone a coral just by snapping in in half, and pieces keep growing,” Kenkel explained, adding that this is not so common for systems that have to undergo sexual reproduction.

Thanks to this method, the researchers were able to put genetically identical individuals into different environments and distinguish clearly between the effects of genetics and those of the surroundings.

While there was some prior evidence in a lab setting that genetic diversity was beneficial, this study provides solid support for this restoration strategy since it was performed on a reef. The setting was “as real as we can make it,” Kenkel said.

Like a rodeo

But a reef comes with associated challenges, which Million experience first hand. When seas were rough, “you’re kind of holding on for dear life as you’re getting pushed around and trying to get your photos” of the corals while also keeping the scaling objects still, he said: “It’s like a rodeo.”

In any case, Million’s research will very likely contribute to his goal back in 2016. Coral reefs provide essential ecological and economic services, as the paper explains, sustaining biological diversity, supporting local communities and maintaining a tourism industry worth billions of dollars.

Varying the genes is one of many strategies that are currently being explored in order to preserve them. “In reality, there is not a unique action, and it is the converging of scientists’ work what will give the higher chances of survival for coral reefs in the Anthropocene,” said Gonzalo Pérez-Rosales, a researcher at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who was not involved in the study.

Indeed, preserving them is key to containing a cascade of global ecosystem deterioration, hence the importance of understanding how best to achieve this. Million said: “If you save the coral, in broad terms, you save a lot more than just the coral.”

Reference: Wyatt C. Million et al., Evidence for adaptive morphological plasticity in the Caribbean coral, Acropora cervicornis, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2203925119

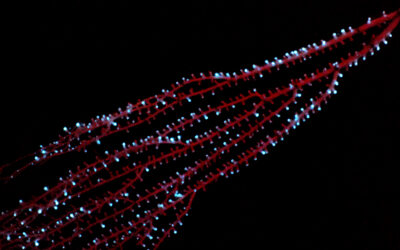

Feature image credit: Francesco Ungaro on Unsplash