Your skin is one of the largest organs of your body and it’s the primary way we interact with the environment around us. Skin disorders are among the most prevalent diseases in the world, and they disproportionally affect children and indigenous populations. Skin health is governed by many factors including genetics, lifestyle, skin microbiome and immune system health. Unravelling this ecosystem and its vulnerabilities is necessary to develop strategies to support patients, which is the goal of a new review from the Auckland Bioengineering Institute (ABI) in New Zealand.

Led by ABI Director Professor Peter Hunter and Research Fellow Dr Jagir Hussan, the review emphasizes the need for big-data analysis, instrumentation, and computer modelling to quantify skin and microbial health in a cost effective and non-invasive manner.

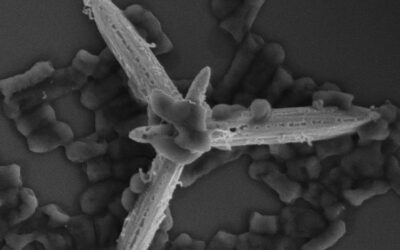

Investigations into systemic effects involving the skin microbiome, such as prosthetic joint infections, acute bacterial and skin structure infections in depressed patients, inflammatory bowel disease etc., are at the frontier of skin-related research. Previous studies have focused mostly on the diversity and abundance of the microbiome and metabolites, but not on the interactions between the microbes, the host, and other host-generated organic compounds.

“What I think our study highlights is the need for a systems-based understanding of the skin’s sophisticated ecosystem,” says Hussan. “We wanted to present the current research and understanding of the skin ecosystem, and then to lay out the key physiological systems active and how they engage with the skin microbiome and vice versa.

“This helped us narrow down some cohesive methods of modelling the skin and the microbiome,” he continued. “It can tell us a lot about the skin but also a lot about the host – this holds enormous potential for health care diagnosis and immunisation.”

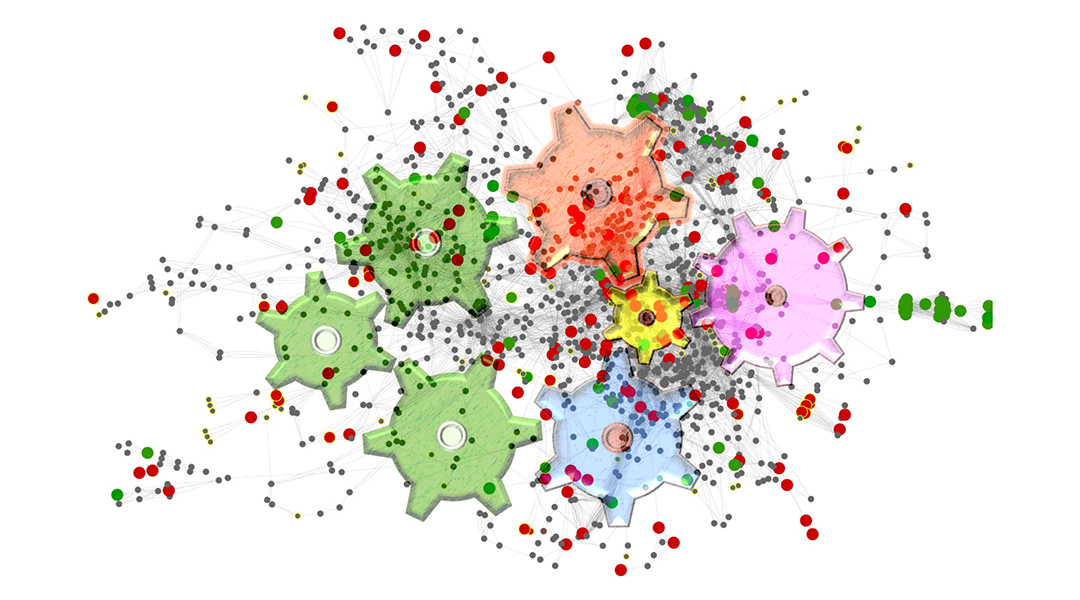

Skin is a sophisticated organ that integrates multiple physiological processes and enables the host to sense and engage with the environment. Each of these physiological processes are equally sophisticated and their coupling results in a complex interaction network. But determining the interactions among its components is a major challenge. The variability of the microbiome across individuals and over time are factors that confound analysis and experimental design.

The skin is a theatre of complex ecological interactions with the environment, functioning both defensively and cooperatively with the microbiome. Microbes can also be exchanged between individuals through cohabitation or indirect contact – this widens the ecological boundary to include people’s choice of pets, clothing, living spaces and more.

Jagir hopes future studies will look at the development of investigative pipelines that couple experiments with instrumentation and computer modelling, which could help manage the complexity of unlocking the secrets of skin health.

Written by: Mr. Reuben Keeling, Auckland Bioengineering Institute, New Zealand

Reference: Jagir Hussan Peter J. Hunter, ‘Our natural “makeup” reveals more than it hides: Modeling the skin and its microbiome’, WIREs Systems Biology and Medicine (2020). DOI: 10.1002/wsbm.1497