Rice University chemist James Tour, left, and graduate student Changsheng Xiang led a team that created a new kind of carbon fiber using graphene oxide flakes. Image: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Large flakes of graphene oxide are the essential ingredient in a new recipe for robust carbon fiber created at Rice University.

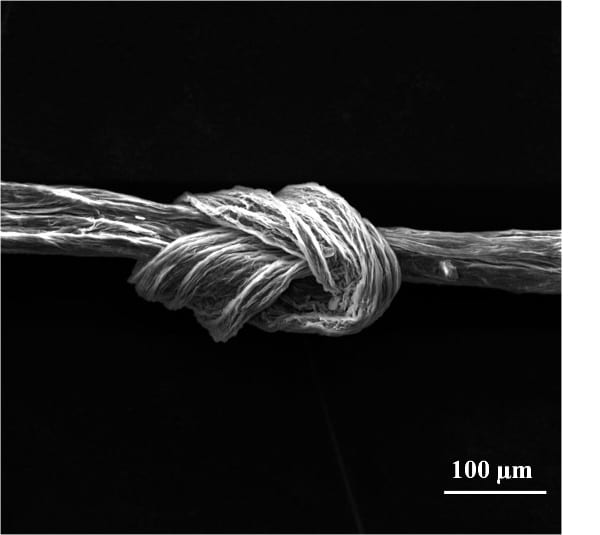

The fiber spun at Rice is unique for the strength of its knots. Most fibers are most likely to snap under tension at the knot, but Rice’s fiber demonstrates what the researchers refer to as “100 percent knot efficiency,” where the fiber is as likely to break anywhere along its length as at the knot.

The material could be used to increase the strength of many products that use carbon fiber, like composites for strong, light aircraft or fabrics for bulletproof apparel, according to the researchers.

“To see this is very strange,” Tour said. “The knot is as strong as any other part of the fiber. That never happens in a carbon fiber or polymer fibers.”

Rice University graduate student Changsheng Xiang holds a weave of carbon fibers created from graphene oxide flakes. Tour Group/Rice University.

Credit goes to the unique properties of graphene oxide flakes created in an environmentally friendly process patented by Rice a few years ago. The flakes that are chemically extracted from graphite seem small. They have an average diameter of 22 microns, a quarter the width of an average human hair. But they’re massive compared with the petroleum-based pitch used in current carbon fiber. “The pitch particles are two nanometers in size, which makes our flakes about ten thousand times larger,” said Rice graduate student Changsheng Xiang.

Like with pitch, the weak van der Waals force holds the graphene flakes together. Unlike pitch, the atom-thick flakes have an enormous surface area and cling to each other like the scales on a fish when pulled into a fiber. The wet-spinning process is similar to one recently used to create highly conductive fibers made of nanotubes, but in this case Xiang just used water as the solvent rather than a super acid.

Bendability at the knot is due to the fiber’s bending modulus, which is a measure of its flexibility, Xiang said. “Because graphene oxide has very low bending modulus, it thinks there’s no knot there,” he said.

A knotted carbon fiber made at Rice University has the same tensile strength along its entire length. That property may make it suitable for advanced fabrics. Image: Tour Group/Rice University.

Tour said industrial carbon fibers — a source of steel-like strength in ultralight materials ranging from baseball bats to bicycles to bombers — haven’t improved much in decades because the chemistry involved is approaching its limits. But the new carbon fibers spun at room temperature at Rice already show impressive tensile strength and modulus and have the potential to be even stronger when annealed at higher temperatures.

Heating the fibers to about 2,100 degrees Celsius, the industry standard for making carbon fiber, will likely eliminate the knotting strength, Xiang said, but should greatly improve the material’s tensile strength, which will be good for making novel composite materials.

The Rice researchers also created a second type of fiber using smaller 9-micron flakes of graphene oxide. The small-flake fibers, unlike the large, were pulled from the wet-spinning process under tension, which brought the flakes into even better alignment and resulted in fibers with strength approaching that of commercial products, even at room temperature.

Source: Rice University