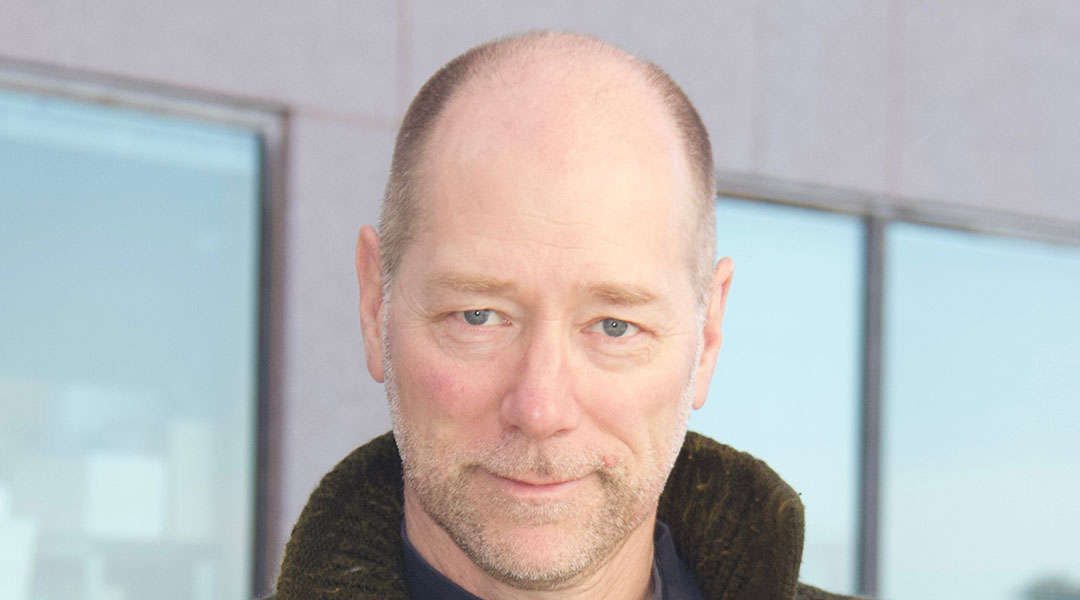

When he was a child, he dreamed of becoming a paleontologist and discovering a new dinosaur all by himself. Today, Michael Sailor, distinguished professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of California, San Diego, is an affirmed leader in nanotechnology and the field of porous silicon.

Professor Sailor’s interest in chemistry began during his childhood, when he used to perform experiments in the backyard of his house involving “smoke, flames, and explosions”—what he terms “interesting reactions”—and even built his own charcoal furnace from bricks, a stainless steel mixing bowl, and his sister’s hair dryer.

This crackling enthusiasm for science was fed during his high school years, when Michael met Ed Duncan and Richard Smith, his high school physics and chemistry teachers. Smith gave him the opportunity to stay alone after school in the chemistry laboratory to perform experiments, with the sole instruction to put all the chemicals away, turn off the instruments, and lock the door on his way out. If a high school teacher were to give that kind of freedom and responsibility to a student today, he would probably get fired, Michael sadly points out. While he doesn’t condone leaving teenagers alone in chemistry labs, he loved that time in his life in which he learned the excitement of independent, curiosity-driven research, and developed a passion for experimenting.

Since then, Michael has come a long way, earning his B.Sc., then a M.Sc. and Ph.D. in chemistry. During his doctorate, he focused mostly on the synthesis and reactivity of metal clusters under Professor Duward Shriver. He carried out post-doctoral studies between Stanford and Caltech, under the supervision of Professor Nate Lewis and in collaboration with Bob Grubbs. Those years, during which Michael studied a hybrid type of solar cell involving silicon and electronically conductive polymers, gave him the opportunity to learn the importance of reaching out to experts to collaborate, as well as the value of multidisciplinary research.

Indeed, Michael feels that a collaborative attitude is the secret to success. Having been educated in a heterogeneous environment made up of chemists, physicists, and engineers, he is a strong advocate of cross-disciplinary research and, as he says, “complex problems require complex solutions”, which need to involve experts in different fields.

As with all long journeys to become what one wants to be, Michael had to face some challenges. Probably the biggest one throughout his career has been raising money to do the research he wants to do. In general, he recognizes this as the most negative trend in science, especially for new generations. He is concerned that “the increasing amount of time that must be spent on writing proposals” goes with “a decreasing amount of money available to support research”. The result of this process is that “creativity is being suppressed in favor of ‘sure bets’ in research that are more incremental than revolutionary”.

But he is optimistic and has special advice for all those young researchers who are starting their careers: “Remember! It is a marathon, not a sprint. But it helps if you can sprint through the entire marathon. Learn how to say no. You need time to think and to do your research and no one will protect that time for you. Don’t forget to have fun”.

Michael is fond of photography and tennis, but if you want to meet him and get more advice, look for him during one of his biking or hiking tours, or when looking for a new object in the deep sky.

Find out more about his research in his recent and comprehensive review, in the Advanced Materials Hall of Fame virtual issue.