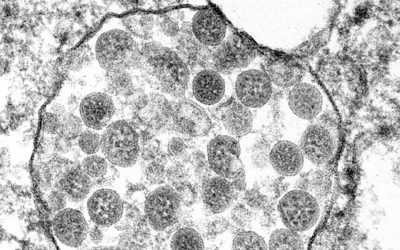

An international team of researchers have warned what should be known to all politicians and leaders across the world; that people’s health should be given just as much priority and safeguards as the economy as some countries emerge from months of lockdown.

Whilst the closure of businesses and borders and the mandating of physical distancing measures have proven effective in slowing the spread and “flattening the curve” of COVID-19 cases, seven months into this new reality it is clear these measures to protect public health have had a devastating toll on many countries’ economy, as well as people’s mental wellbeing as they adjust to life under lockdown.

Because of this, it is unsurprising that governments are keen to get their economies up and running again. But as has been seen, most strikingly in the case of the USA, lifting these restrictions too early, too quickly, or too carelessly can cause a rapid spike in new coronavirus infections. In some places this is seen as a second wave of infections. In the USA, it is suggested that this spike is still the first wave, and that all the progress made on flattening the curve of this wave has been squandered.

It is therefore imperative that any measures to reboot the economy need to take public health into serious and equal consideration.

Publishing in the European Journal of Epidemiology, a team of epidemiologists from the University of Cambridge, the University of Bern, BRAC University, and the National Heart Foundation in Bangladesh, have looked at three community-based lockdown exit strategies, and recommend their scopes, limitations and the appropriate application of such strategies. The research focuses on low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The focus on LMICs is particularly crucial as healthcare systems and diagnostic capabilities may not be well developed, making a second outbreak difficult to control.

Speaking in a press release by the University of Cambridge, Dr. Rajiv Chowdhury, lead author of the paper, said, “Successfully re-opening a country requires consideration of both the economic and social costs. Governments should approach these options with a mind-set that health and economy both are equally important to protect — reviving the economy should not take priority over preserving people’s health.”

The three strategies examined are “sustained mitigation”, “zonal lockdowns”, and “rolling lockdowns”.

Sustained mitigation

This strategy has shown positive results and success stories across Europe, and includes nationwide measures such as mandatory mask wearing in closed spaces and public transport, effective contact tracing, and large-scale testing. However, a major factor that makes sustained mitigation a success story is the relatively high income of countries in which this strategy is adopted.

By contrast, a lot LMICs simply do not have the financial resources or infrastructure to make sustained mitigation feasible, particularly with regards to contact tracing and testing capacity. What’s more, hospital infrastructure may not be enough to keep up with demand. The authors point to the example of ventilators, and how India has only 48,000 for their 1.3 billion people.

Zonal lockdowns

As the name suggests, these are lockdowns specific to a particular area, rather than nationwide restrictions. These are usually implemented when there is a local cluster of coronavirus outbreaks whilst the rest of the country has things relatively under control. Zonal lockdowns have happened in recent weeks in Gütersloh, Germany, Leicester, UK, and parts of Beijing, China, which were forced to re-enter lockdown months after emerging from the nationwide lockdown imposed at the start of the pandemic.

However, as with sustained mitigation, the success of zonal lockdowns relies on resources and the appropriate infrastructure; real-time data feedback, population surveillance, and good reporting and testing. Pakistan, for example, tests only 0.09 per 1000 people on a daily basis, compared to 0.52 per 1000 in France. Containing the outbreak within the quarantined zones can also be hugely problematic, with zones in India showing infection rates 100 to 200 times higher than the rate outside the zone.

Rolling lockdowns

This third strategy is already advised for LMICs by the WHO. They involve periods of strict social distancing measures to ease the rate of infection and therefore burden on under-equipped health services, followed by a period of easing such restrictions to allow the economy to “breathe”. Doing this on a rolling basis could have positive effects on flattening the curve.

A study by the same team published in May showed in a model that having 50 days of social distancing measures followed by 30 days of relaxing the restrictions, could reduce the virus reproduction number to 0.5. Professor Oscar Franco, lead author of the study, said in a press release: “Rolling lockdowns need be flexible and tailored to the specific country. The frequency and duration of the lockdowns or relaxed periods should be determined by the country based on local circumstances. They don’t necessarily need to be nationwide — they can also involve a large zone or province with very high incidence of COVID-19.”

A rolling lockdown may better suit countries whose economies are already precarious, as opposed to an indefinite and total lockdown seen in higher-income countries.

What is clear in a global pandemic is the strength and recovery of the economy isn’t the bottom line; public health and healthcare provisions are just as important in safeguarding to ensure that countries can recover from this pandemic not just economically, but socially and politically.