Following a heart attack, a patient’s blood changes, becoming a chaotic environment of dead cells, inflammatory markers, and other proteins. In this new environment, a specific type of blood cell — the macrophage — changes and becomes better suited for debris clean up and repair.

This specific switch may play a role in recovery, and gives researchers a new therapeutic angle to explore.

Acute myocardial infarction, otherwise known as a heart attack, occurs when a blocked vessel cuts off blood supply to the heart, causing some of the muscle to die. As the tissue dies and falls apart, a message is sent via the blood.

“Your heart suffers a heart attack, and has to signal to the rest of your body, something is wrong, we need help here to repair,” explained Lieve Temmerman, senior scientist at Maastricht University. “The blood is basically the system that’s used for the signal.”

Temmerman and her colleagues at the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Maastricht University Medical Center published a study in Advanced Science showing how macrophages respond to this message.

Highly plastic cells

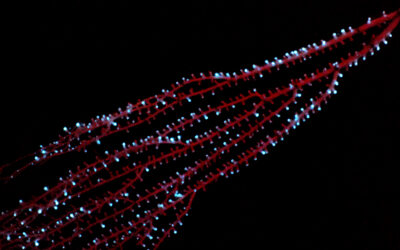

Macrophages are white blood cells that reside in organs all over the body and act as sentinels for pathogens or trauma — they are constantly sensing their surroundings and reacting. Biologists refer to the ability to change in response to the environment as plasticity, and according to Temmerman, macrophages are notoriously plastic.

This propensity to change, coupled with their importance for carrying out damage repair, is exactly why Temmerman wanted to see how they responded to the post-heart-attack blood environment.

To investigate, she exposed macrophages to a cell culture containing blood serum from patients who had had a heart attack or who were healthy controls. She then measured everything from the cells’ ability to engulf particles, withstand apoptotic challenge (a cellular death pathway), changes in metabolism, and cell cycling. She also looked at which genes and signalling pathways in the cell are involved in these changes.

According to Temmerman, the macrophages underwent changes that make them better suited for debris cleanup and repair. “The main thing that we see is that the cells really respond by taking up more, they are more active, they phagocytose more, that’s really clear,” she said.

Along with the enhanced debris cleaning, different immune pathways and genes were activated in the post-heart-attack macrophages, and these subtle changes allowed Temmerman to go a step further.

She built a profile of these subtle cellular changes and began correlating these with patient outcome. “We could also see some of these pathways that we found are actually correlating with either a bad prognosis or a good prognosis [for the patient],” she explained, “and that gives you an entry to try and find the drug candidate that could maybe skew your macrophage towards the good or the bad.”

Searching for a heart attack treatment

Next, she compared her macrophage profiles to databases of experiments in which cells were exposed to drugs, looking for a drug or target that produces a similar profile to the ones seen in her results.

There was a match between profiles associated with poor outcomes and cells treated with a drug that targets a cell receptor called prostaglandin E2. This receptor is associated with cardiac repair in mice studies, and targeting it with a pharmaceutical might nudge the macrophages toward a better response and improve a patient’s chances.

Temmerman and her colleagues are excited by this discovery as it could one day lead to a heart attack treatment for patients. Pending more research and clinical trials, a drug intervention may one day be given for a short period after a heart attack, which helps macrophages switch into repair mode and improves prognosis.

Reference: Lieve Temmerman, et al., Blood milieu in acute myocardial infarction reprograms human macrophages for trauma repair, Advanced Science (2022). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202203053

Feature image credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto