Chemically reduced graphene oxide is a good substrate for high enzyme loads, and activities comparable with those found in solution can be achieved on this surface, as shown by Chinese scientists.

Chemically reduced graphene oxide is a good substrate for high enzyme loads, and activities comparable with those found in solution can be achieved on this surface, as shown by Chinese scientists.

Graphene oxide (GO) is an interesting substrate for absorption and immobilization of biological compounds because of its stability, low toxicity, and unique chemical, electrical, and mechanical properties. It has been used in biomolecule detection and as a drug carrier, and more recently as a substrate on which to immobilize enzymes for catalytic use. However until now, such attachment has had to be done either covalently, or via electrostatic interactions between the enzyme and the GO surface. Covalent bonding may alter the properties of the enzyme by changing its shape, but the electrostatic interactions can also affect enzyme activity.

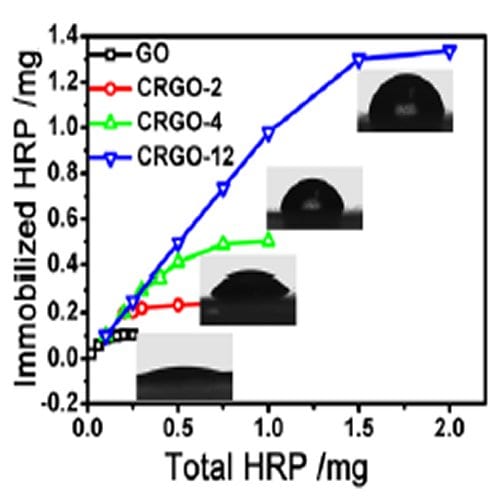

Scientists have started to experiment with a modified kind of GO called chemically reduced graphene oxide (CRGO) to overcome this problem of attachment. CRGO has fewer surface functional groups than GO, so should perturb the enzyme on it less. Now, a team led by Jingyan Zhang at East China University of Science and Technology and Shouwu Guo at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China, has looked systematically at the loading and activity of enzymes on CRGO with varying degrees of reduction.

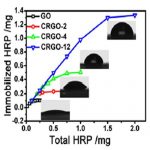

The team found that the more reduced the CRGO, the higher the possible loading of the enzyme, and that loadings of up to 60 times those possible on classically used materials were possible with CRGO. They found that the high loading was caused by hydrophobic interactions between the CRGO surface and the surface of the enzyme molecules, rather than the electrostatic interactions present with regular GO.

But when the team looked at the activity of the enzymes, they got quite a surprise. While one enzyme (horseradish peroxidase; HRP) was much less active than in solution, another (oxalate oxidase; OxOx) was nearly as active and retained up to 90% of its activity even after ten cycles of use, depending on the extent of CRGO reduction. Previous studies on immobilization of OxOx, e.g., on solid beads, have yielded much lower activities. The scientists attribute this finding to the particular structures of the two enzymes and how they bind to the surface. Some enzymes will change conformation on binding to the hydrophobic surface, which involves a dehydration step; this may affect the activity of the enzyme, while it appears that OxOx does not alter so much.

This new way to immobilize OxOx on CRGO while retaining high activity is very promising for clinical determinations of oxalate. The team believe that their method can be extended to use for other enzymes that retain their structure upon hydrophobic binding and dehydration, and that it has applications in detection and as a molecular carrier.