In the pursuit of clean sources of power researchers are turning to nature for inspiration, be it in the form of developing artificial photosynthesis, novel photovoltaic structures, or improved optical structures for use as either anti-relfective layers or light-absorbing layers. Reporting in Advanced Optical Materials, researchers from the Weizmann Insitute of Science in Israel have characterised the structure of plant leaves (including the leaves of the common houseplant f. elastic, the so-called rubber plant) in 3D on a microscopic scale.

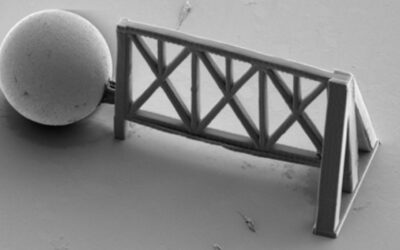

The photosynthetic pigments result in a steep light gradient through the thickness of the leaf so that, while it may be light-saturated near the surface, deeper down there would expected to be little or no light. So how does the leaf convert solar energy as efficiently as it does? By combined electron microscopy, optical microscopy, and microCT the researchers found that a regular distribution of amorphous calicum carbonate bodies known as cystoliths occurs in the leafs of the plant species used in this study. Micro-scale modulated fluorometry showed that the cystoliths scatter the incoming light so that it is distributed more evenly throughout the leaf. In this way the excess light from the surface can be absorbed instead by the deeper layers, which would otherwise be light-deprived.