In many places around the world flooding is a major problem, inflicting large costs to society. Moreover, these impacts are potentially worsened across the globe as socio-economic development places more people and assets in harm’s way. Climate change alters the extent, magnitude, and likelihood of flood events, which further complicates how society needs to manage flooding moving forward. However, it must also be kept in mind that flooding is a rather spatially contained threat as certain areas are much more likely to flood than others.

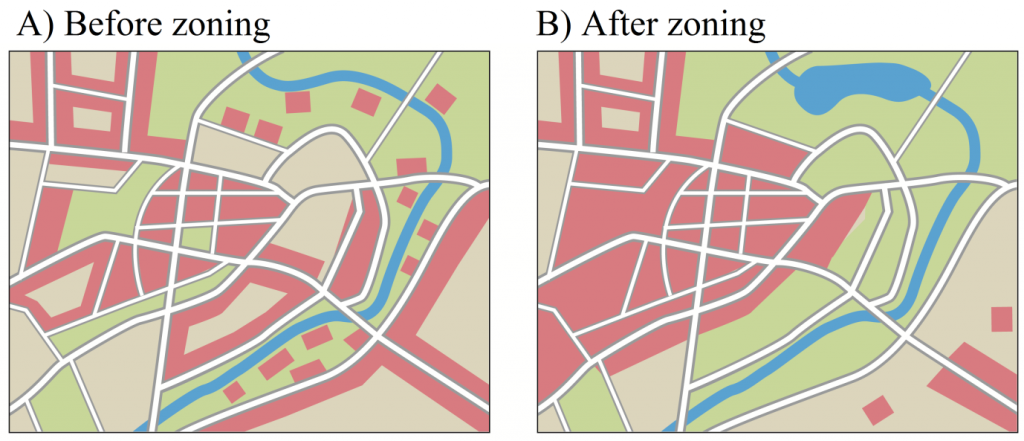

This is where zoning policies can be useful as they are targeted risk-management policies for certain areas. Take the image below for example; it shows that in order to limit the negative impacts of floods, development needs to be refocused into safer areas, along with introducing lakes and better environmental conditions that help limit the extent of potential floods.

There are several examples of these regulations in practice. For example, France has zoning regulations via risk prevention plans, so-called PPRs. A second example is in the USA, where the Federal Emergency Management Agency uses flood risk zoning in order to determine insurance premiums, insurance purchase requirements, and building regulations that are part of the National Flood Insurance Program.

While there are several example of zoning policies currently in action, they must be evaluated in terms of their total costs and benefits to society. Ideally, a zoning policy will generate a larger value for benefits than costs, and cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is the standard way of organizing the information on costs and benefits in a systematic way to support decision making.

In a recent study published in WIREs Water, Dr. Paul Hudson of University of Potsdam and Professor W. J. Wouter Botzen of VU University Amsterdam provide examples of previously conduced CBAs, which were gathered for two reasons: i) to combine their results to see if the average result shows a net benefit or net cost to society from zoning to protect against flooding, and ii) to synthesize an evaluation framework which can be more widely employed.

Their extensive review detected 9 studies from which the average result showed that the zoning policies could generate between $1.03 and $2.20 of benefits per dollar of costs generated if areas with a flooding probability of up to 1% are zoned.

This shows the success of zoning in limiting flood impacts in a socially advantageous way. However, the study also indicated the sheer breadth of policies that can be considered as zoning, ranging from building codes to limit flood damage to comprehensive land-use plans and modifications. This range of strategies complicates the process of conducing CBAs. Therefore, the analysis of the benefits and costs of a zoning policy cannot be confined to a single disciplinary field.

“Zoning regulations operate at the intersection of planning, law, property rights, flooding, and economics research,” says Dr. Hudson. “Evaluating these regulations requires us to move beyond disciplinary boundaries.”

Rather, deeper and more sophisticated interdisciplinary research needs to be conducted moving forwards, and should involve engaging practitioners and local residents in order to better understand, evaluate, and employ the results of future CBAs.

He adds that “the most important direction of future research and activity is simply to evaluate more current or proposed zoning regulations in a wider range of contexts.”

Kindly contributed by the authors.