Image credit: ESO, ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser

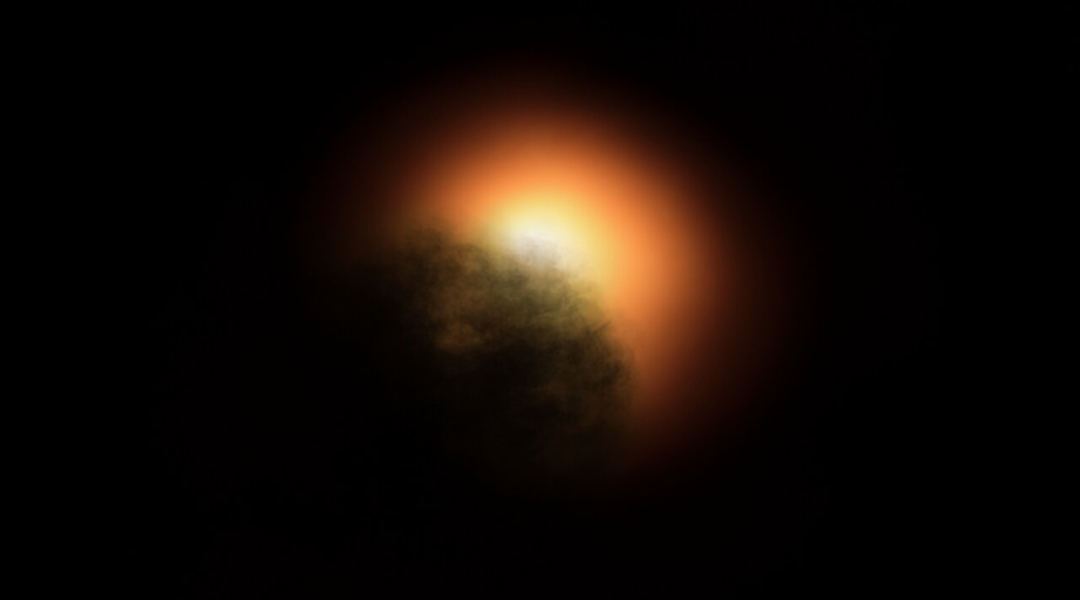

New observations by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope suggest that the unexpected dimming of the supergiant star Betelgeuse was most likely caused by an immense amount of hot material ejected into space, forming a dust cloud that blocked starlight coming from Betelgeuse’s surface.

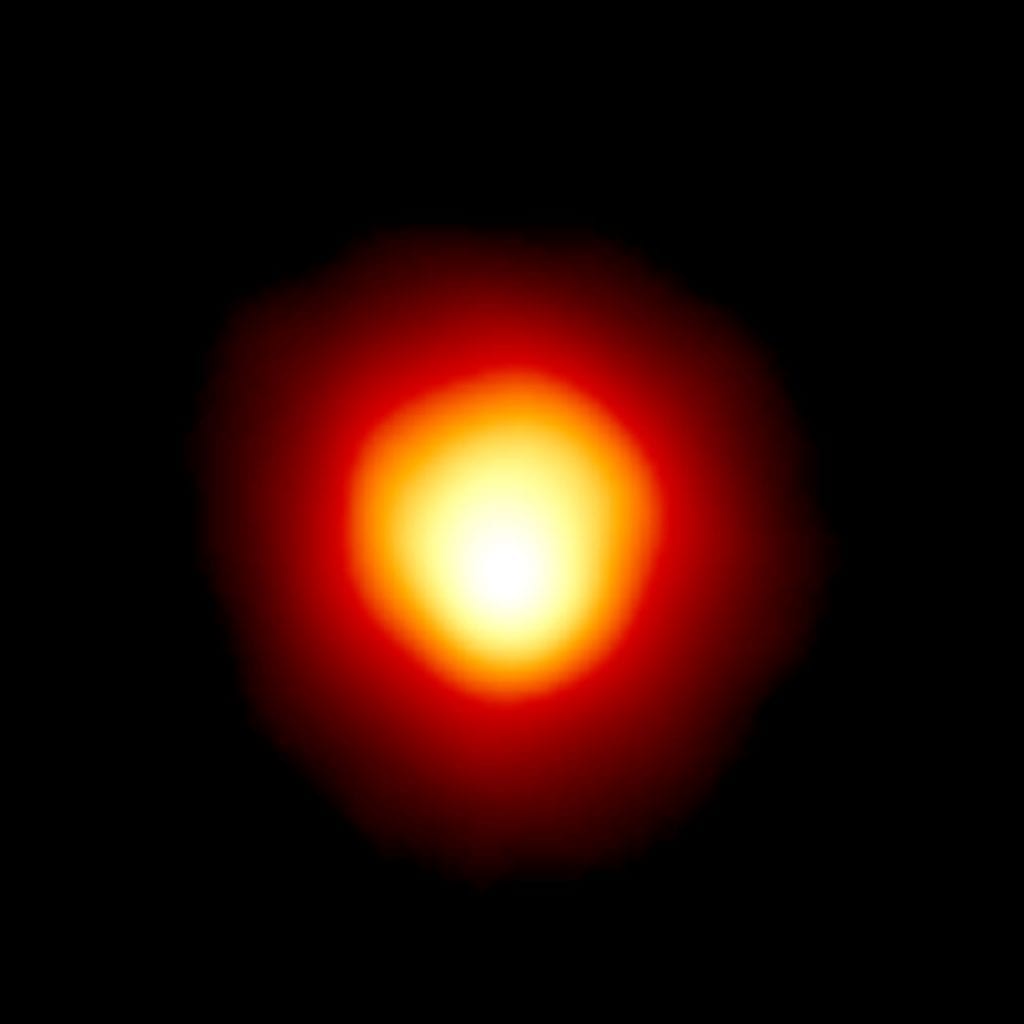

Betelgeuse is an aging, red supergiant star that has swelled in size as a result of complex, evolving changes in the nuclear fusion processes in its core. The star is so large that if it replaced the Sun at the centre of our Solar System, its outer surface would extend past the orbit of Jupiter. The unprecedented phenomenon of Betelgeuse’s great dimming, eventually noticeable to even the naked eye, began in October 2019. By mid-February 2020, the brightness of this monster star had dropped by more than a factor of three.

This sudden dimming has mystified astronomers, who sought to develop theories to account for the abrupt change. Thanks to new Hubble observations, a team of researchers now suggest that a dust cloud formed when superhot plasma was unleashed from an upwelling of a large convection cell on the star’s surface and passed through the hot atmosphere to the colder outer layers, where it cooled and formed dust. The resulting cloud blocked light from about a quarter of the star’s surface, beginning in late 2019. By April 2020, the star had returned to its normal brightness.

Several months of Hubble’s ultraviolet-light spectroscopic observations of Betelgeuse, beginning in January 2019, produced an insightful timeline leading up to the star’s dimming. These observations provided important new clues to the mechanism behind the dimming. Hubble saw dense, heated material moving through the star’s atmosphere in September, October, and November 2019. Then, in December, several ground-based telescopes observed the star decreasing in brightness in its southern hemisphere.

“With Hubble, we see the material as it left the star’s visible surface and moved out through the atmosphere, before the dust formed that caused the star appear to dim,” said lead researcher Andrea Dupree, associate director of The Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. “We could see the effect of a dense, hot region in the southeast part of the star moving outward.”

“This material was two to four times more luminous than the star’s normal brightness,” she continued. “And then, about a month later, the southern hemisphere of Betelgeuse dimmed conspicuously as the star grew fainter. We think it is possible that a dark cloud resulted from the outflow that Hubble detected. Only Hubble gives us this evidence of what led up to the dimming.”

The team began using Hubble early last year to analyse the massive star. Their observations are part of a three-year Hubble study to monitor variations in the star’s outer atmosphere. The telescope’s sensitivity to ultraviolet light allowed researchers to probe the layers above the star’s surface, which are so hot that they emit mostly in the ultraviolet region of the spectrum and are not seen in visible light. These layers are heated partly by the star’s turbulent convection cells bubbling up to the surface.

“Spatially resolving a stellar surface is only possible in favourable cases and only with the best available equipment,” said Klaus Strassmeier of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) in Germany. “In that respect, Betelgeuse and Hubble are made for each other.”

Hubble spectra, taken in early and late 2019 and in 2020, probed the star’s outer atmosphere by measuring spectral lines of ionised magnesium. From September to November 2019, the researchers measured material passing from the star’s surface into its outer atmosphere. This hot, dense material continued to travel beyond Betelgeuse’s visible surface, reaching millions of kilometres from the star. At that distance, the material cooled down enough to form dust, the researchers said.

This interpretation is consistent with Hubble ultraviolet-light observations in February 2020, which showed that the behavior of the star’s outer atmosphere returned to normal, even though in visible light it was still dimming.

Although Dupree does not know the cause of the outburst, she thinks it was aided by the star’s pulsation cycle, which continued normally though the event, as recorded by visible-light observations. Strassmeier used an automated telescope of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics called STELLar Activity (STELLA) to measure changes in the velocity of the gas on the star’s surface as it rose and fell during the pulsation cycle. The star was expanding in its cycle at the same time as the convective cell was upwelling. The pulsation rippling outward from Betelgeuse may have helped propel the outflowing plasma through the atmosphere.

The red supergiant is destined to end its life in a supernova blast and some astronomers think the sudden dimming may be a pre-supernova event. The star is relatively nearby, about 725 light-years away, so the dimming event would have happened around the year 1300, as its light is just reaching Earth now.

Dupree and her collaborators will get another chance to observe the star with Hubble in late August or early September. Right now, Betelgeuse is in the daytime sky, too close to the Sun for Hubble observations.

Press release provided by ESA/Hubble

*The team’s paper will appear in the journal, Astronomical Journal