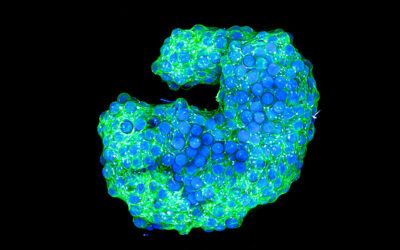

Over the past two decades hydrogels have become a popular material in areas of regenerative medicine, such as tissue engineering, due to their biocompatibility, flexibility, and ability to act as supports for new cell attachment and growth. As such, they have the potential to circumvent the need for organ donors by allowing doctors to recreate damaged tissue and organs using the patient’s own cells.

They are generally composed of polymer networks that absorb water to create a porous structure that allows the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients, and safely degrade once their function is complete, leaving behind healthy, regenerated tissue. However, flexible hydrogels cannot be applied to treatments that require structural strength and stability, such as bone repair.

“Despite being similar to the natural tissue of the body … hydrogels are notoriously difficult to work with as they are inherently weak and structurally unstable. They do not easily attach to solids which means they often cannot be used in mechanically demanding applications,” said Dr. Behnam Akhavan of the Univeristy of Sydney.

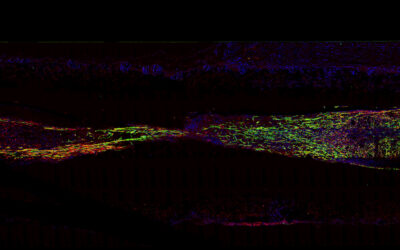

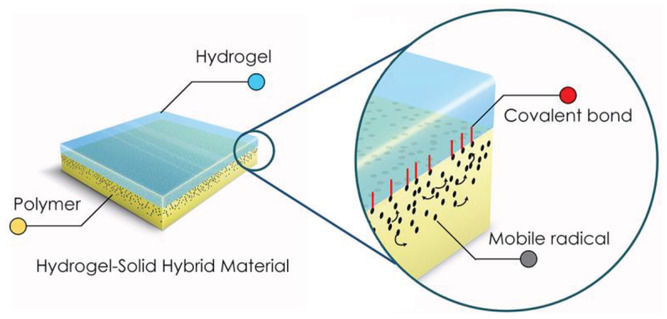

Behnam recently led a study with Professor Marcela Bilek — recently published in Advanced Functional Materials — in which the team developed a new universal plasma technology to attach hydrogels to rigid polymer materials, such as silk with Teflon and polystyrene polymers, using surface‐embedded radicals.

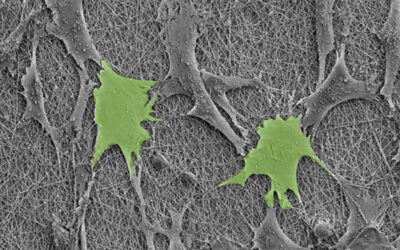

The technique, called plasma immersion ion implantation, is a reagent-free means of creating covalent bonds, and has applications in many fields including aeronautics, microelectronics, and medicine. Here, high voltage pulses are used to accelerate ions from a plasma through the hydrogel toward the polymer’s surface where they penetrate and leave a layer of reactive radicals in their wake. This results in covalent attachment of the two layers, as molecules in the hydrogel that are in contact with the polymer surface react with the newly generated surface-embedded radicals.

The plasma process is carried out in a single step, generates zero waste, and does not require additional chemicals that can be harmful to the environment.

“Our group’s unique plasma process … enables us to activate all surfaces of complex, porous structures, such as scaffolds, to covalently attach biomolecules and hydrogels”, said Bilek. “These advances enable the creation of mechanically robust complex-shaped polymeric scaffolds infused with hydrogel, bringing us a step closer to mimicking the characteristics of natural tissues within the body.”

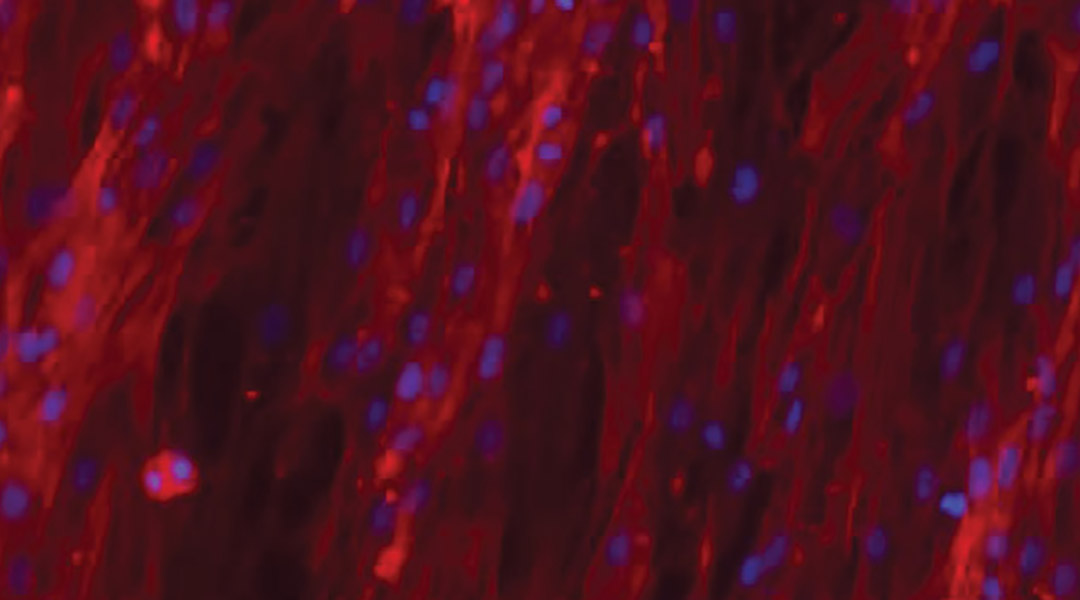

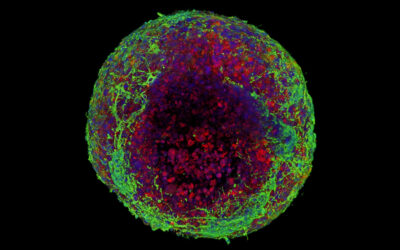

To demonstrate the hybrid hydrogels’ biological capabilities, the team functionalized them with fibronectin, a protein involved in a number of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, growth, and migration. In other reported cases, chemical cross-linkers were required to tether fibronectin to hydrogels. Cells on the hydrogels modified with the PIII surface treatment demonstrated cell adhesion and spreading.

“The ability to retain native biofunctionality of the ECM proteins, while they are affixed to the structure, enables the provision of cell‐instructive cues for tailored biological applications,” wrote the authors. “Our results show that radical‐functionalized polymers provide excellent solid platforms for the creation of robust solid−hydrogel hybrid structures that are of interest for applications in biomedical engineering and beyond.”

Reference: Rashi Walia, et al. ‘Hydrogel−Solid Hybrid Materials for Biomedical Applications Enabled by Surface‐Embedded Radicals‘ Advanced Functional Materials (2020). DOI: 10.1002/adfm.202004599