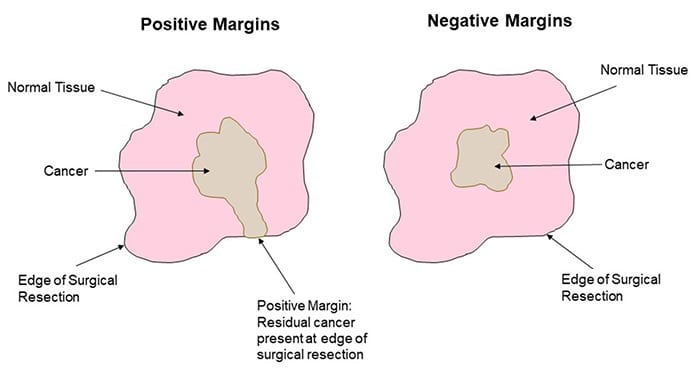

For common solid cancers such as breast, lung, colorectal, prostate, skin, and soft tissue carcinoma, surgical excision is often the best opportunity for a cure. Unfortunately, however, cancer cells can sometimes be inadvertently left behind. This situation, called a positive surgical margin, carries a worse prognosis for the patient because the cancer is more likely to recur.

In many cases, additional therapies like chemotherapy or radiation are needed; but these therapies can carry debilitating side effects, and often cannot fully negate the effect of the positive surgical margin.

Dramatic improvements in anesthesia and surgical instrumentation have allowed surgeons to access tumors that previously were unresectable. However, the most crucial element of cancer surgery—the surgeon’s ability to tell apart the tumor from normal tissue—has barely changed since 3000 BC, when Egyptians chronicled the first attempts at surgery on breast tumors. Tumor cells are microscopic, and often the surgeon can only estimate what is normal or abnormal. Nowadays, most surgeons continue to rely on white light to tell the difference between tumor and normal tissue. This reliance is a critical limitation to improving cancer outcomes.

However, research into how to better visualize tumor cells during surgery is underway, and is discussed in a recent review article in WIREs Systems Biology and Medicine.

In fluorescence imaging, compounds known as probes bind specifically to cancer cells and appear in various colors to distinguish cancer cells from normal tissue. Some compounds are specific to vessels, ducts, or nerves, and can help cancer surgeons preserve vital structures to offer better functionality after surgery.

In breast cancer, probes against folate (a vital nutrient for cell division) and matrix metalloprotease (an enzyme responsible for tumor invasion) are being used in clinical trials. In lung cancer, indocyanine green is being used to label lymphatics and more accurately identify regional lymph nodes. Lectins, vascularized endothelial growth factor, and cathepsins—all compounds involved in tumorigenesis—are being targeted in colorectal cancer, and probes with specific applications in prostate and pancreatic cancer are also being evaluated in clinical trials.

One day soon, surgeons could be using fluorescence-guided surgery to more completely remove cancers, while preserving the normal surrounding tissue.

Kindly contributed by the Authors.