Image credit: Kiara Worth

World leaders reached an agreement this week at COP26 and signed what is now known as “The Glasgow Pact.”

Among a slew of other agreements, countries have acknowledged that more needs to be done as the current pledge agrees on further action to curb emissions by 2030, more frequent updates on progress, and support for developing nations.

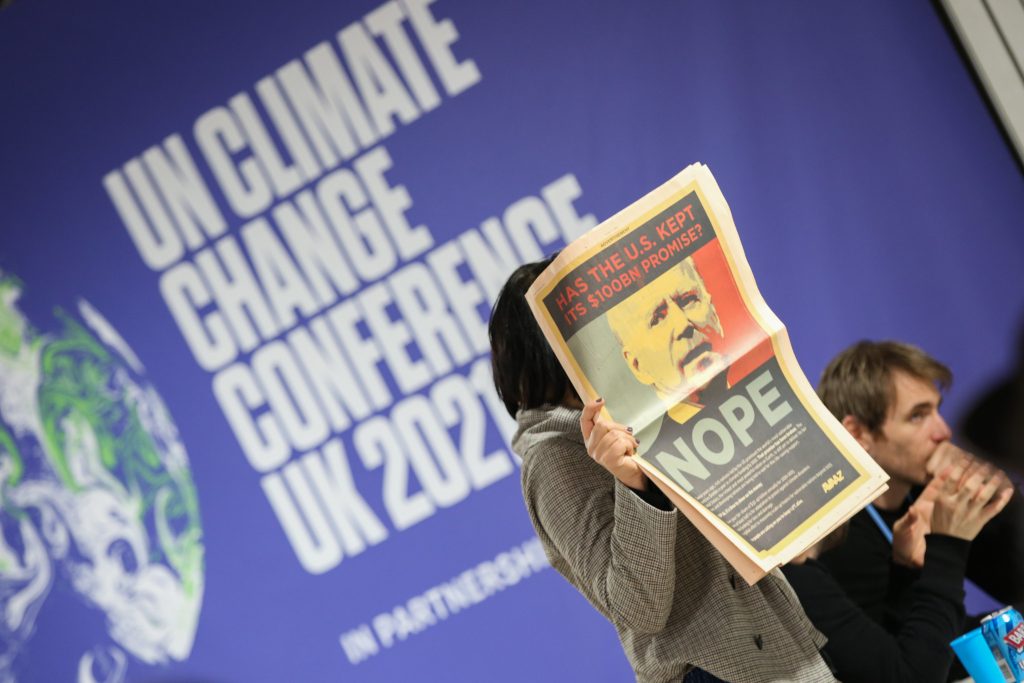

Expectations for COP26 were high given that it was the first major United Nations meeting since the Paris Agreement in 2015. However, some scientists, activists, and the public are of the opinion that this year’s outcomes were lackluster. The pledges made provide hope that this crisis is being taken seriously, but whether words will translate into reality is yet to be seen.

A lack of priority

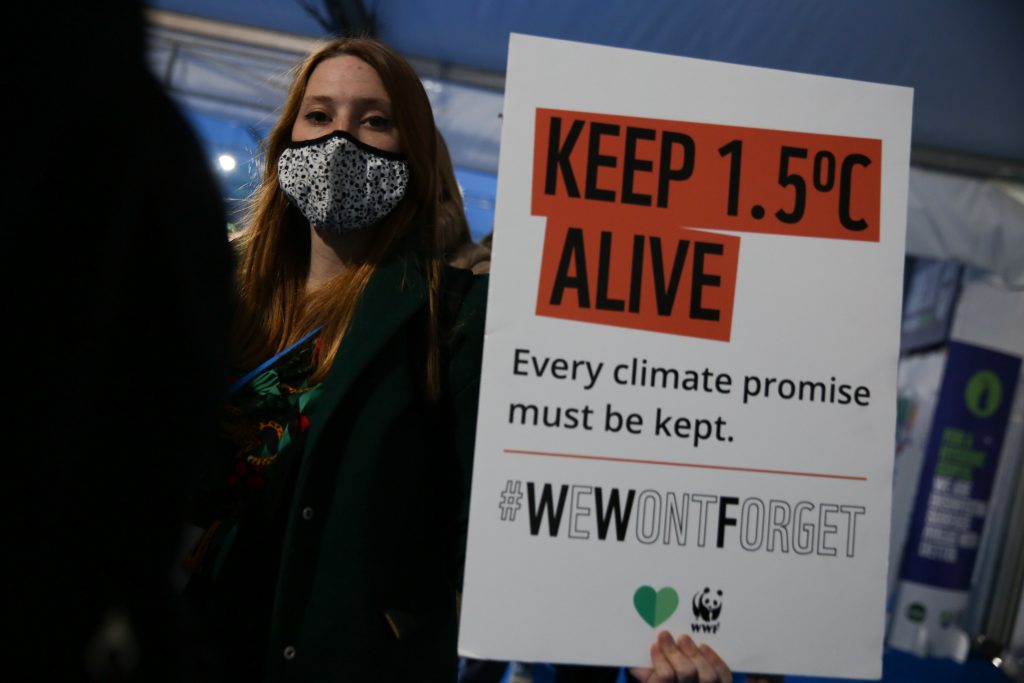

Perhaps the most alarming result is the inevitability that the world will not meet the prescribed 1.5°C limit of global warming. Even though crossing that boundary is not a cataclysm, it was of a symbol of unity, a line in the sand drawn by scientists for all governments to strive for to mitigate the worst of the climate crisis.

Given current projections, even if countries meet the targets they set for the next decade, global warming is still projected to rise 2.4°C above pre-industrial levels. This is a perfect illustration of how performative these conferences can be: how a lack of priority can derail a common goals and how apathy from delegates can compound with interest. A last-minute watering down of the agreement to include the phrasing “phase-down” instead of “phase-out” in relation to coal further highlights that crucial climate solutions are not at the forefront.

Some hope can still be gleaned as this was the first-time coal was explicitly mentioned in any COP report. But for many this feels like one step forward, two steps back.

Scientists have been calling for collective, global action to combat this existential threat, and more needs to be done to ensure meaningful steps are taken over the next decade to meet promises enshrined in this agreement.

Accountability

The debate around accountability has changed over the last decade, with many now recognizing that only a handful of fossil fuel companies are responsible for a staggering 35% of all global carbon and methane emissions.

To achieve the objectives set out during COP26 requires “a whole of economy transition.” The private sector’s role, specifically those companies operating in the energy industry, needs to be questioned and shifted if real change is to happen.

The UN itself has called on the private sector to evaluate its objectives in the grand scheme of net zero. In its “Race to Zero” campaign published in 2020, they write, “Breakthroughs cannot happen if individual entities work in isolation from one another. The challenges of competition and inertia often deter ambition, where individual actors cannot make the first move without putting themselves at a distinct disadvantage in the near term.”

In light of this, though perhaps not as substantial as many groups would have wanted, some progress was made at COP26, with 23 nations pledging to phase out coal power while also committing to scaling up clean power. The countries committing include five of the world’s top 20 coal power generating countries, including South Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam, Poland, and Ukraine.

In addition, a number of countries, together with financial institutions, have signed a commitment to end international public support for “the unabated fossil fuel energy sector” by the end of 2022. Funds will instead prioritize support for the clean energy transition.

While this does not limit funding for national fossil fuel energy subsidies, the UN estimates that $17 billion a year could be moved out of fossil fuels and into clean energy alternatives as a result. “This is a historic step. It is the first time a COP presidency has prioritized this issue and put a bold end date on international fossil fuel finance,” wrote COP26 representatives.

Adaptation and global equity

COP26’s commitment to adaptation finance and steps toward addressing global inequity was an interesting outcome of the conversations.

Adaptation finance is the idea that funding a country’s ability to adapt to the climate crisis will cost less in the long term. The World Resources Institute estimates that every $1 USD put toward climate adaptation can return anywhere from $2 to $10.

Wealthy nations have become so by burning fossil fuels, but a common theme in climate activism is stopping further fossil fuel use to curb emissions. This leaves nations in the Global South in a difficult position as they must now build wealth and infrastructure at an accelerated pace, while simultaneously pulling their populations out of poverty. The conversation around adaptation finance during COP26 involved more specifically characterizing a definition that both developed and developing countries agree on, as all countries have different goals.

The final Glasgow Climate Pact itself “urges developed country Parties to urgently and significantly scale up their provision of climate finance, technology transfer and capacity-building for adaptation so as to respond to the needs of developing country Parties as part of a global effort, including for the formulation and implementation of national adaptation plans and adaptation communications.”

This indicates that the delegates are aware of the privilege of developed nations and that combating climate change must include some form of reparation payments. However, it’s important to proceed with caution, as fiscal climate commitments to developed nations have been hollow in the past.

Cause for hope

Some governments have officially declared a climate emergency, and history has shown what can be achieved when humanity is collectively mobilized. Climate denialism is waning in light of substantial evidence, and for the first time, nations appear to be on the same side when it comes to acknowledging and addressing the problem.

The headliner has of course been that we are on track for 2.4°C of warming if all of the countries make good on their existing pledges, which is itself unlikely. The reality is we’re probably on track for a higher temperature.

There are positive takeaways from COP26, however. The first is that progress is going to be more frequently assessed – annually instead of every five years – which is a testament to the urgency now given to the problem.

The second is the fact that fossil fuels were specifically called out in this agreement. In the past, governments have been unwilling to make that mention, but this new draft stipulates a transition away from fossil fuels, and everyone is on board on paper. The speed and level of commitment is not enough, but it’s a step toward having a majority of energy generation being produced through renewable sources over the next 20 to 30 years.

All of this is happening at a time when climate disasters are routinely breaking records. Parts of the world will become unlivable, forced migrations will continue to happen, growing populations will add to climate and food stress, but this is no longer an abstract threat that people need to be convinced of.

We’ve reached a tipping point, and things will get worse before they get better, but collective action and a shift toward a “greener” future are finally on the table.

Written by: Kieran O’Brien, Kevin Hurler, and Victoria Corless