Image credit: Alex Block on Unsplash

During the past 30 years of extensive political debate around global climate change, participants have largely ignored the role that curbing population growth could play in dealing with it.

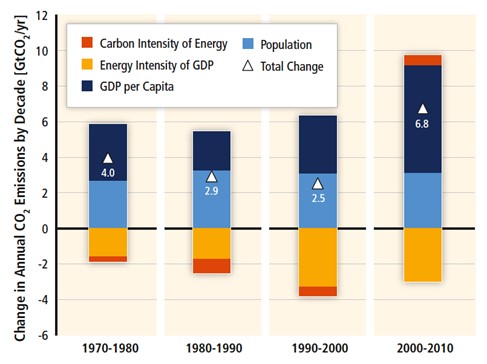

On its face, this might seem strange since our scientific models have long identified population growth as one of the two primary drivers of humanity’s increasing greenhouse gas emissions. The IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report noted that, “Globally, economic and population growth continue to be the most important drivers of increases in CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion”.

Carbon emissions driven by population and economic growth

According to a recent report from Working Group I for the IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report, greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase along with global temperatures, which is still driven by growing human populations and increased economic activity.

The mystery deepens when we note that studies have repeatedly shown that limiting population growth is among the cheapest, most effective means to limit and help societies adapt to climate change. And unlike unproven technologies, such as carbon capture and sequestration, or dangerous ones like solar radiation management, modern contraception has been proven safe and effective. Yet during the recent COP26 meetings in Glasgow, little was said about limiting population growth during negotiations, and nothing made its way into the final agreement.

Odd, no? Yet on reflection, the oddity vanishes since climate policy discussions are tightly constrained by conventional economic thinking, which regards limits to growth as anathema. Until recently, neither the scientific nor the philosophical communities showed much interest in challenging this taboo. Among policymakers, proposals to limit climate change have focused on technological fixes or efficiency improvements within a context of continued growth.

This longstanding approach, however, has proven itself a failure. Greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase and disruptive climate change has come on more quickly than expected.

Impacts that scientists predicted would show up in the second half of this century are happening now. Worries about how our grandchildren’s lives might be constrained have been replaced by worries about our children’s lives, or even our own.

Addressing population must be part of a global response to climate change

In the face of an obviously unraveling global ecosystem, people are starting to question once-sacred cows, such as the possibility of endless economic growth or humanity’s ability to safely manage unimaginably complex systems — even if such ideas haven’t yet made their way into national policies or international agreements.

One example of this developing open-mindedness (or perhaps panic) has been a surge in scientific discussions around population in relation to climate change. A 2019 “Warning of a Climate Emergency,” signed by over 11,000 scientists, forthrightly described continued increases in human population and the world gross domestic product as “profoundly troubling signs” of ecological decline.

It stated: “The world population must be stabilized — and, ideally, gradually reduced — within a framework that ensures social integrity.” Addressing population, therefore, must be part of humanity’s response to global climate change.

Thankfully, philosophers and ethicists have also begun to acknowledge this. Ten years ago, a review of the climate ethics literature found almost no discussion of population matters. But a follow up review I conducted, and just published, uncovered numerous books and articles exploring the issue, and vigorous debates regarding all aspects of population policy, from contraceptive availability to government incentives regarding family size.

Population needs to be incorporated into climate strategies

Many philosophers now believe, in the words of philosopher Colin Hickey and colleagues, that “climate change is among the most significant moral problems contemporary societies face, in terms of its urgency, global expanse, and the magnitude of its attending harms,” and that “population plays an important role in determining just how bad climate change will be.”

While it is possible to put forward plans for mitigating climate change that don’t address population, many agree that such an approach is morally irresponsible since it “falls short of offering a clear and reasonably certain pathway to avoiding dangerous climate change.”

True, making population policy may take us into morally fraught territory, but ignoring population policy is even more problematic given the high costs of failure to limit climate change. Besides, every nation has population policies, even if they don’t call them that: policies that allow or prohibit couples from choosing the number of children they have, for example, or that incentivize or discourage large families. The real question is whether these policies will be made with reference to justice, sustainability, and the common good, or not.

My recent literature review found that human rights concerns loom large in debates about population policy. On the one hand, opponents of population stabilization efforts often point to past human rights abuses, such as forced sterilizations under India’s emergency decree in the 1970s, to justify their opposition. On the other hand, family planning proponents note that most social pressure and government coercion, now as in the past, involves forcing women to have more children than they want to have, not fewer.

Global climate change brings further rights concerns to the table since it directly threatens human rights, particularly the rights to basic physical security and sufficient food, water, and shelter.

One of the most challenging issues in population ethics involves what to do when individuals’ desire for large families leads to environmental degradation. Robust discussion of this has been hampered by worries that doing so might stigmatize children from large families, or unjustly blame citizens in poorer countries who have contributed little to climate change. In a crowded world in rapid ecological decline, however, such discussions are needed.

In the end, there appears to be a fairly robust consensus among climate ethicists that societies must balance reproductive rights against other human rights, and those rights with responsibilities.

Climate justice beyond “just us”

Beyond human rights concerns, other species arguably have a right to continued existence free from untimely anthropogenic extinction, whether caused by climate change or other impacts of human overpopulation.

Many ethicists emphasize the need to fairly balance human and nonhuman interests, so that human numbers don’t overwhelm and crowd out other species. With the proviso that justice isn’t about “just us”, affirming a proper balance between human reproductive rights and responsibilities becomes part of sustaining the flourishing of life in all its forms.

Obviously, this concern for the well-being of other species has yet to find its way into actual climate policy choices, as shown most recently at COP26.

Faced with the reality of global climate change and its devastating impacts, climate ethicists have begun to add their voices to the scientists and environmental activists who support addressing population and facing limits to growth.

Across all ethical approaches, there appears to be a strong consensus on the value of choice-enhancing policies that reduce human fertility, such as securing universal access to modern contraception and providing equal rights and opportunities for women. There is also strong support for government policies that incentivize smaller families, considerable support for policies that disincentivize larger ones, and little to no support for punitive policies.

It appears that ethicists who ask what justice demands regarding population policy in a warming world may find reasonably clear answers. Whether our societies can apply those answers and create realistic and effective climate policies is a further question.

Written by: Philip Cafaro

Reference: Philip Cafaro, Climate ethics and population policy: a review of recent philosophical work, WIREs Climate Change (2021). DOI: 10.1002/wcc.748.