Welcome to one of our first guest columns, where active researchers can share their views on topics relevant to materials science. To start us off, we invited Professor Geoffrey Ozin of the University of Toronto to share his honest opinion on the current state of nanoscience research. He took up the challenge and provided us with two inaugural articles. Here, he shares his views on the immense amount of reported nanomaterials, while in the second article, he focuses on the future of the promising nanomaterials.

It is a nagging question that has been asked before in other areas of chemistry when the rate of production of molecules or materials reaches what is perceived as a saturation point in the supply chain.

I think this is a question on most of our minds these days as we try to wrestle which way to go scientifically and technologically with the exponentially growing bank of nanomaterials and ponder the gigantic efforts and funding levels devoted to the discovery and utilization of these nanomaterials in diverse areas of nanotechnology.

To me it seems that these tiny pieces of matter are the new materials proving ground of chemistry and physics, materials science and engineering, biology and medicine for pure unadulterated basic research, and play an unquestionable central role in the multidisciplinary quest for discovery and development of new and improved products and processes.

Aside from all the good stuff we all know about, I sense something is rotten in the state of nanomaterials. With more than four decades of research under my belt beachcombing for exciting new materials in many different fields, I am sufficiently long in the tooth scientifically, to have witnessed the rapid rise and fall of all sorts of exciting new classes of molecules and materials. I have that sinking feeling that nanomaterials might suffer this fate unless some strategic changes in direction are implemented pretty soon.

This boom and bust phenomenon is most often driven by scientific oversell and overproduction of molecules and materials by enthusiastic practitioners of their art, hyped expectations that cannot be realized and promises that cannot be fulfilled. This rise and fall of new classes of molecules and materials is often accompanied by loss of interest by funding bodies in continuing to support the work and the flight of top notch researchers from the area not keen to keep the flame alight and looking for something better to keep them occupied.

Recall after the heydays of organometallic and cluster chemistry, researchers in the field turned their attention to the use of organometallics and clusters as reagents and catalysts in organic and polymer synthesis, and precursors in materials chemistry from which blossomed a new genre of pharmaceutical chemistry, organometallic polymer chemistry and solid state chemistry, as well as a host of new journals to cater to their publication needs.

Historically there has been a critical point of boom and bust in most branches of chemistry when granting agencies switch off the money supply, industry loses interest in supporting the work and researchers wind down their activities and redirect their efforts to more fertile and productive pastures.

I sense this situation looming with all the nanomaterials being thrust upon us in far too many papers and in far too many journals from every conceivable corner of the world.

This is not to say that amongst the mass of nanomaterials being reported every day there are not a few distinctive ones that can change the prevailing view in the field. These are few and far between and suffer the danger of their significance being overlooked and their impact under-appreciated in the tsunami of irrelevant reports. Often quality falls as hoards of researchers jump on a bandwagon like scientific sheep. The effect of this is to muddy the waters and diminish the visibility of the work of black swans with a need to distinguish themselves, so they lose interest and move on to what they perceive as bigger and better things with more satisfying scientific rewards and the field dies.

After roughly two decades of observing the appearance of nanomaterials with every imaginable organic and inorganic composition, size, shape and surface, it is disturbing that we still are unable to make them truly monodispersed on demand. We still only know the single-crystal X-ray structure of less than a handful of nanomaterials, and the cytotoxicity of the majority of them still remains unknown!

These days I have been wondering what should we be doing with all these nanomaterials? We are reaching a point where we will soon have as many nanomaterials as molecules but without the perfection trademark of molecules.

It seems to me that to give nanomaterials the status of molecules and approve their long-term survival as the building blocks of myriad nanotechnologies, we have to start a discussion on what are the really big questions, both intellectual and practical, and hopefully encourage young scientists to take a risk with more challenging problems in their chosen field instead of wasting their time working on trivia that nobody cares about.

I believe young researchers should be encouraged, without penalty, to tackle big and important problems even though there is a greater chance of failure rather than forcing them to play safe in a field and continue to turn the handle of incremental technical improvements, when it is clear enough is enough. A change of attitude towards young researchers would inspire creativity and enable science, technology and society to move forward faster and further.

I am of the opinion that we have reached a point in the development of nanochemistry where we have an oversupply of nanomaterials and unless we assume the scientific responsibility to take the field to a higher level of development it will lose ground around the world as both students and stake holders will see nanomaterials as a just a means to an end rather than an exciting platform for new science with identifiable technologies.

I imagine most would agree that nanomaterials will have a recognizable impact in healthcare, clean energy and water, and all things related to the environment and sustainability. And while new nanomaterials will likely underpin these technologies surely it is time to ask, do we really need to keep on churning out more and more nanomaterials to solve these problems?

I think it is now time to improve the basic and directed science for making, understanding and utilizing what we have already banked in our vault of nanomaterials and in the list below I have taken the liberty of offering up ten recommendations, not set in stone, to begin a discussion on what is next:

1. learn how to make them more perfect and elucidate means to define the degree of perfection,

2. delineate metrics that demarcate the boundaries between molecular, nanoscale and bulk forms of matter

3. establish situations when perfection is beneficial and when imperfection can be tolerated

4. understand better their surface and bulk chemistry

5. devise synthetic methods and characterization techniques for composition tuning and doping

6. control and characterize surface and bulk defects

7. improve control over their self-assembly and disassembly

8. report information on their shelf-life in dry and humid air and under vacuum, their colloidal stability in different solvents, and how long they live when stimulated thermally, electrically and photolytically

9. reduce-to-practice prototype devices, products or processes for your pet nanomaterial, and if successful, figure out how to scale up its production to industrial proportions in a

n economical and safe manner, and

10. facilitate the transition of your idea to innovation that works and helps humankind.

Maybe in another NanoChannel article we can contemplate a future in which nanomaterials can be made atom precise and structure perfect to order, and can be chemically and physically manipulated in ways we handle molecules. I think by perfecting imperfection and with a treasure chest of ideal nanomaterials the field of nanochemistry will return to its chemistry roots!

Geoffrey A. Ozin

Materials Chemistry and Nanochemistry Research Group

Center for Inorganic and Polymeric Nanomaterials, Chemistry Department

80 St. George Street, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, M5S 3H6, Canada

E-mail: [email protected]

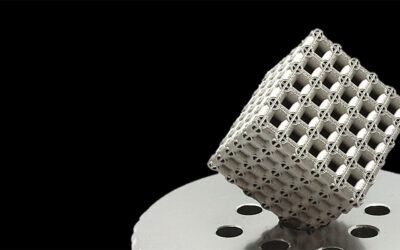

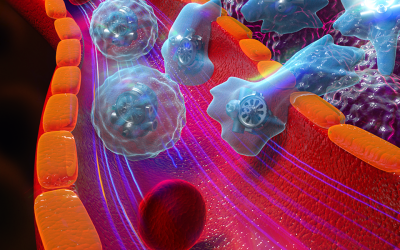

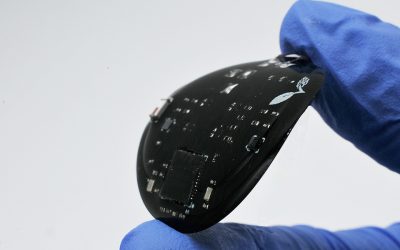

The cover image of this article is a composite of various images/schemes of nanomaterials. Created by Vladimir Kitaev.