Though it was designed and built with the observation of galaxies and celestial objects million and even billions of light-years away, one of the most pleasing aspects of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) thus far has been the impact it has had within Earth’s backyard.

The $10 billion USD space telescope has thus far captured incredible images of planets, like Saturn and Jupiter, from its position at a gravitationally stable point in the Earth-Sun system located one million miles from our planet. But the latest image from our solar system taken by the JWST may be its most spectacular and impressive yet.

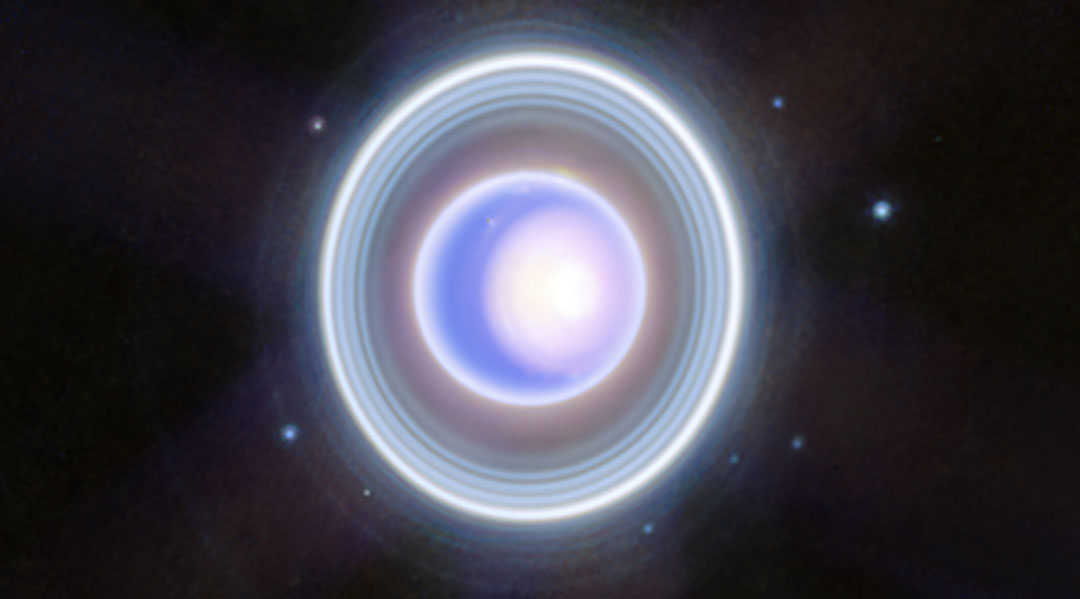

The space telescope has managed to catch an incredible view of the ice giant Uranus. But, whereas previous images of Uranus have seen it appearing as a featureless and inert marble, this new look released to the public on Monday, December 18, shows an altogether more vibrant and dynamic world.

One of the key reasons the JWST image of Uranus looks so different from the image taken by the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1985 is that the prior mission viewed that planet in observable light, while the JWST sees the ice giant in infrared.

Captured in the image are the seasonal features of Uranus — which whirls around the Sun, tipped on its side — including its polar ice cap. Also visible are its rings, one of which is the faint and diffuse “Zeta ring” located close to the planet. This ring, which was first detected by Voyager 2 in 1986 and then spotted again by the Keck Telescope in 2003 and 2004, will be of particular interest to astronomers as it has never been seen in such detail before.

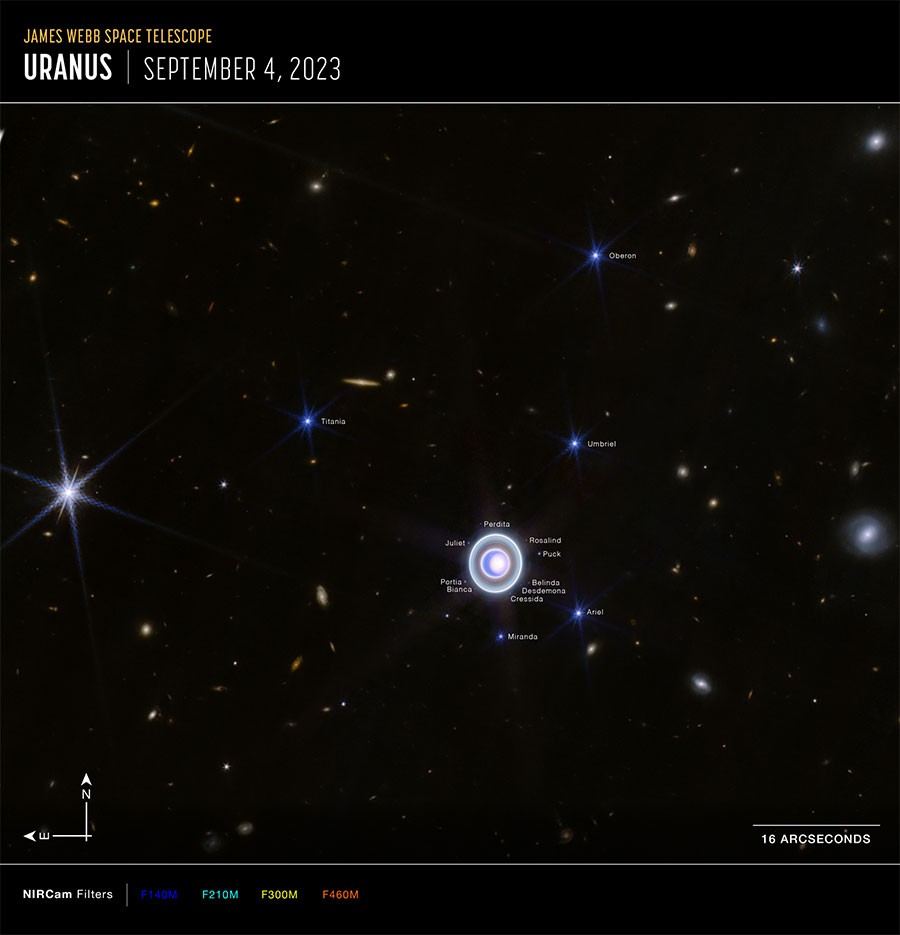

Not to be left out, with its extreme sensitivity, the JWST also managed to capture a handful of the 27 moons that orbit this ice giant, which is the seventh planet from the Sun, even spotting some small moons that dwell within the rings of Uranus — albeit not for the first time.

Thirteen of the 27 known moons of Uranus are visible in the new JWST image, including Titania, Umbriel, Miranda, Puck, and Juliet. Literary enthusiasts will notice that all the moons of Uranus are named after characters that appear in the works of William Shakespeare and Alexander Pope.

Examining Uranus’ atmosphere in detail

One of the details revealed by this infrared view of Uranus is a seasonal cap of thick clouds located at the north pole of the planet. In the image, this cloud cover takes the form of a bright white glow with a thick dark lane at its lower extremities. This polar cap is more visible when the north pole of the ice giant is pointed toward the Sun when it is receiving and reflecting more sunlight.

Uranus takes around 84 Earth years (30,687 Earth days) to orbit the Sun, and its 98⁰ axial tilt causes it to have the most extreme seasons in the Solar System.

At the south of this cloud cover, which faces to the right of the image thanks to Uranus’ tilt, are bright spots, which are massive storms raging in the atmosphere of the planet, which is four times as wide as Earth. The number of storms that Uranus experiences and where these manifest are dependent on the planet’s season and meteorological conditions.

In 2028, the ice giant will have its pole directed toward our star again, and this will signal a 21-year-long winter for the other half of Uranus. At this time, the JWST can be used to observe what changes this prompts in the structure of this polar cap. This will help better understand the atmosphere of Uranus, and together with Zeta ring observations, this will provide information that will help design future missions to the ice giant planet.

Feature image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI