More than forty years after the global concern over a mystery illness that caused the outbreak of the deadly AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, HIV infections can now be dealt with using antiretroviral treatments. A diagnosis is today no longer a death sentence.

Although most people with HIV can now live long and healthy lives, there remains no permanent cure and their bodies will never be rid of the virus completely, requiring chronic treatment. However, this is not true for everyone.

A rare group of patients called HIV controllers have been found to maintain a very low viral load and a functional immune system after stopping antiviral treatment. Scientists theorize that they could provide a functional cure, improving the health and mental burden of HIV patients if only they could understand how it happens. “The goal of drug-free HIV control or remission is a key goal for the field and for our patients,” said Jonathan Li, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, HIV/AIDS clinician at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Once antiretroviral therapy is stopped, the virus rebounds quickly in the vast majority of patients”.

“But there is a unique group of individuals, termed post-treatment controllers, who can maintain viral suppression even after treatment discontinuation,” he added.

The mechanisms by which this group can keep HIV at bay remains nonetheless a mystery but, in a paper published by Li and his colleagues in Science Translational Medicine, the team hopes to provide a starting point for future HIV mitigation strategies.

“With the availability of highly effective therapies against HIV, […] treating patients for a long time, keeping the viral load undetectable and stopping antiretrovirals after a while has been considered in the hope that [patients’ immune systems] will be able to control the residual virus,” said Luis Menéndez-Arias, principal investigator at the “Severo Ochoa” Molecular Biology Center (CBMSO) in Madrid and an expert in HIV and antiviral therapies who was not involved in the study.

Early antiretroviral therapy is determinant

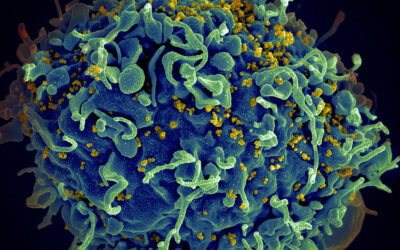

Viruses are parasites that hijack a cell’s biological machinery to use it as a viral factory, producing millions of copies of the virus until the cell can literally hold no more and ruptures, continuing the viral cycle of production.

The devastating effects of HIV reside in two main factors: first, they colonize and destroy immune cells, essentially rendering patients defenseless, making any minor infections a life-threatening risk. Secondly, the HIV virus has such a high mutation rate that new versions of the virus are constantly being produced, leading to resistance against the body’s immune response and any pharmaceutical treatments.

“Early HIV treatment seems to lower the barrier to achieving therapy-free HIV control,” said Li. “In our previous study, we already found that early antiretroviral therapy initiators were more likely to become post-treatment controllers than those who initiated therapy during chronic infection.”

Early therapy restricts HIV’s capacity to replicate and mutate, hence minimizing the viral repertoire and tipping the balance of the internal fight against the infection in favor of the immune system.

According to Menéndez-Arias, “The most important conclusion [of the work presented by Li’s group] is that HIV control by the patient’s immune system is only possible in those cases in which treatment was started early and there was a strong neutralizing antibody response — the body’s main weapon against pathogens– as well as little diversity in the viruses that were present in the patient when treatment began”. The latter meaning that the virus did not have enough time to mutate.

Neutralizing antibodies — building the perfect weapon

When immune cells on patrol find intruders, they sound the alarm, alerting our “defense production headquarters”, the spleen, where our body begins to search for the perfect weapon to eliminate the threat. An important part of this arsenal is neutralizing antibodies, which are proteins produced by the immune system that attach themselves to the intruder, in this case the HIV virus, neutralizing it (as their name implies) by preventing the pathogen from carrying out its biological function.

But HIV is tremendously sneaky and fighting this infection turns into a lifelong battle.

In the current study led by Li, the team focused on which of these antibodies found in HIV controllers proved successful in keeping HIV at bay. The scientists showed for the first time that such neutralizing antibodies contribute to drug-free suppression of HIV, providing a plausible mechanism for the immune control of the disease by this rare group of HIV patients.

As the antiretroviral drugs inhibit the virus, preventing it from extensively multiplying and mutating, they allow the maturation of neutralizing antibodies. Applying early therapy therefore buys the immune system time to prepare and develop.

Predicting drug-free control of HIV

“Understanding how this rare group of infected individuals can maintain [drug-free] control of HIV will help us predict which patients can safely stop antiretroviral therapy,” said Elmira Esmaeilzadeh, postdoctoral researcher at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and first author of the paper. According to her, studying these patients will provide insights into the design of new therapies that are able to induce HIV remission even after treatment —providing a functional cure.

However, it is difficult to study HIV controllers since they can only be identified after treatment interruption. Due to the risk that comes with stopping treatment, this is generally only recommended as part of a clinical trial.

Menéndez-Arias thinks that with studies like this “we could ideally predict how well patients could control the infection and whether they would benefit from treatment interruption”. But we need to be cautious.

“These studies involve a limited number of patients –in the case of the study led by Li, six patients who had remission after treatment was stopped and six who did not,” he added.” Besides, it is not always easy to treat a patient as early [as the study proposes], since a great deal of people only become aware of being infected after showing some symptoms of AIDS”.

This May marks the 40th anniversary of the identification of HIV as the underlying cause of AIDS, the first step made towards stopping the deadly toll of a highly stigmatized disease. Four decades after, although the stigma has not completely disappeared, combined antiretroviral therapy has changed the impact of a former terminal disease to a chronic condition –in countries where the treatment is widely available.

The search for a cure for HIV still continues and significant inroads have recently been made, such as the five people who have recently been cured of HIV, but, according to Li, we should not overlook the fact that the existence of these individuals shows that HIV remission is an achievable goal.

Reference: Elmira Esmaeilzadehet al., Autologous neutralizing antibodies increase with early antiretroviral therapy and shape HIV rebound after treatment interruption, Science Translational Medicine (2023). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq4490

Feature image credit: Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash | Respect my HIV protest in London, November 2021