Combining a light-activated therapy and antibiotics, scientists are finding a way to attack tumors while eliminating the bacteria inside them — an approach that could make cancer vaccines more effective

It is well established that certain bacteria found inside tumors help them evade the immune system, making it harder for the body to fight back. By removing them in this dual-pronged strategy, they can enhance in situ tumor vaccines — a type of cancer immunotherapy that helps the body create its own cancer vaccine.

“We aimed to bridge these two areas by designing a nanoplatform capable of simultaneously eradicating tumor cells and their intracellular bacterial accomplices,” said Jie Cao, professor at Qingdao University and the study’s lead scientists.

To do this, Cao and her team used photodynamic therapy, where a light-activated compound called a photosensitizer is used to kill cancer cells after generating reactive oxygen species, with antibiotics to target both tumor and bacteria simultaneously.

“This dual-targeting strategy not only addresses antibiotic resistance concerns [by reducing the need for prolonged antibiotic use] but also disrupts the symbiotic relationship between tumors and bacteria, offering a promising avenue for improving cancer treatment outcomes.” said Cao.

Vaccines made in the body

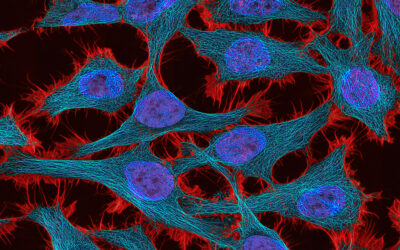

In situ vaccines are a developing cancer treatment platform that targets tumors directly using the body’s own immune system. Tumor cells are broken down during treatment, releasing specific biological markers from the tumor, which then alert the immune system to recognize and fight the cancer — without needing to make a vaccine in the lab.

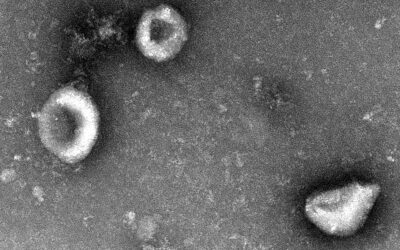

However, a roadblock facing in situ vaccines is bacteria that tend to gather in tumor cells. From facilitating the spread of cancer to other parts of the body, to suppressing the immune system, these tumor-residing bacteria are so deeply entrenched inside the tumors that they become difficult to treat with traditional antibiotics and negatively affect the performance of the vaccines.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate [photodynamic therapy] and [the antibiotic] doxycycline into a single nanoplatform for the dual purpose of killing tumor cells and eliminating tumor-resident bacteria to induce in situ vaccination,” said Cao. “While [photodynamic therapy] and antibiotics have been explored separately in cancer therapy, their combined use to target both tumor cells and bacteria while reshaping the immunosuppressive tumor environment represents a significant innovation.”

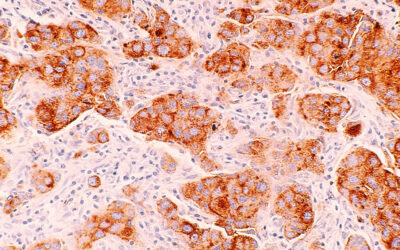

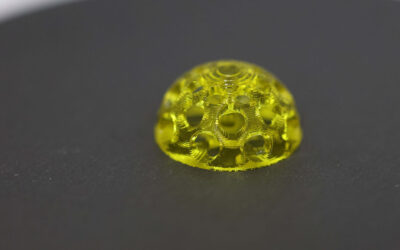

Doxycycline and a light-activated compound called photosensitizer CyI — which the team specifically designed to create increased levels of reactive oxygen species — were combined in an exosome, which is essentially a special “wrapper” for both compounds that was derived from cancer cells and allows them to covertly infiltrate the tumor.

Once inside, the exosome breaks down to release its cargo, which can then begin taking the tumor down from the inside. The doxycycline, besides its antibacterial properties, has been reported to damage mitochondria, leading to more available oxygen in the tumor. This oxygen in turn can further fuel CyI’s production of reactive oxygen species, which damage and kill both tumor cells and bacteria, releasing antigens to trigger an immune response.

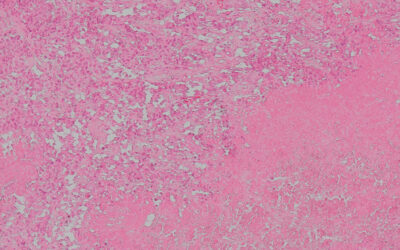

The team tested their platform in mouse models of breast cancer, monitoring tumor growth and body weight over the treatment period, as well as survival rate compared to a control group.

They found that tumor growth weakened over time in treated mice, whereas tumors continually grew in the control group. Treated mice saw a 60% survival rate 50 days after treatment began, compared to the controls, of which none survived.

The scientists also looked at levels of bacteria in the tumors following treatment, finding significantly lower levels in treated mice compared to controls. The team also observed higher levels of immune cells in the tumor tissue, suggesting that by eliminating the bacteria, the platform reduced immunosuppression and promoted the release of further antigens, triggering a heightened immune response for the in situ vaccine.

Other control experiments were also performed, including using only liposome-encapsulated CyI, doxycycline, or both, always with light irradiation and no exosome “wrapper”.

Besides the doxycycline-only group, these showcased delayed tumor growth, increased survival and antibacterial effects, and heightened immune responses compared to controls, with improved results from the combined doxy and CyI group indicating synergistic effects between them; although not as effective as the complete platform, suggesting the ability of the exosome “wrapper” to better infiltrate tumor cells.

Potential and further testing

In addition to breast cancer, Cao and her team foresee this strategy being applicable to a wide range of cancer types, including pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma, as well as cancers with a strong bacterial association, like colorectal cancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma.

The team further expects this strategy to highly complement existing cancer therapies, such as chemo- and radiotherapy, enhancing their efficiency and offering additional support, particularly against cancers that are resistant to such approaches.

“Bringing our combined [photodynamic therapy] and doxycycline approach to human trials and eventually the clinic involves several challenges that need to be addressed,” mentioned Cao. Questions still exist regarding the exact molecular mechanisms, as well as whether repeated treatments could induce resistance in tumors or even cause damage to healthy tissues, which the team seeks to explore in future studies.

“Further preclinical studies in additional animal models are needed to validate the efficacy and safety of the approach across different cancer types and stages,” Cao said.

This vaccine platform is still in early research, requiring further testing before it can reach human trials — a process that could take years. While combining photodynamic therapy and antibiotics shows promise for boosting cancer vaccines and reducing antibiotic resistance, Cao emphasizes that more studies are needed to ensure its safety and effectiveness before clinical use.

“By addressing these obstacles and systematically moving through the necessary steps, we can pave the way for this innovative therapy to benefit cancer patients in the future,” she concluded.

Reference: Zequn Li, Jie Cao, et al., Tumor-Resident Intracellular Bacteria Scavenger Activated In Situ Vaccines for Potent Cancer Photoimmunotherapy, Advanced Healthcare Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1002/adhm.202404271

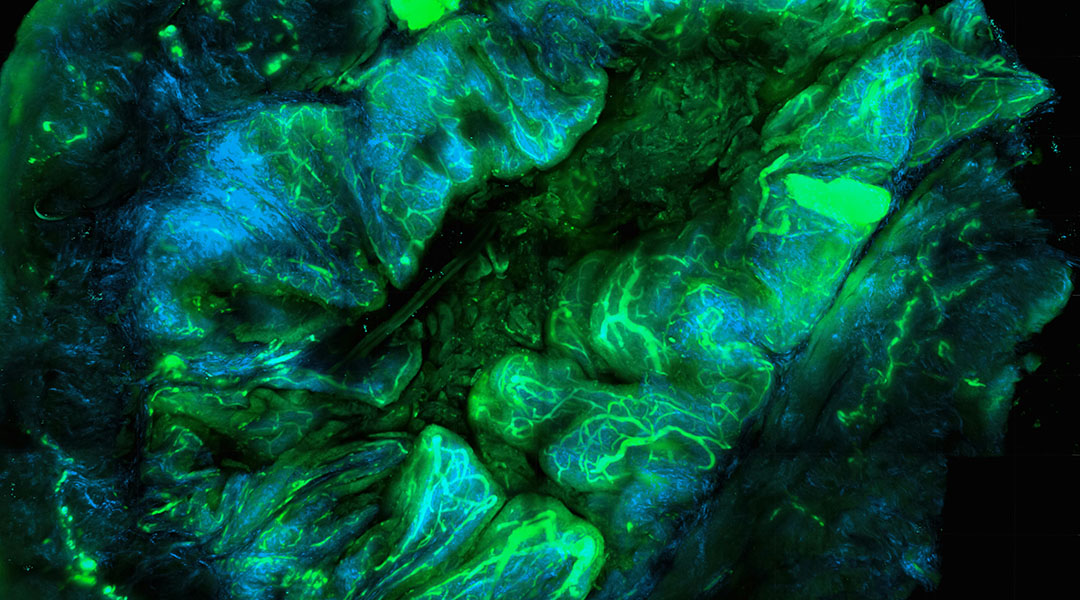

Feature image credit: National Cancer Institute on Unsplash