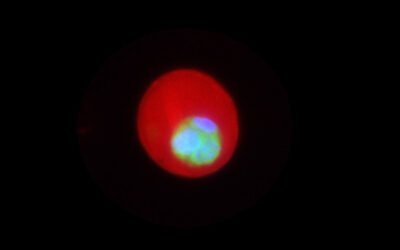

Image credit: Lee Haines et al. 2020

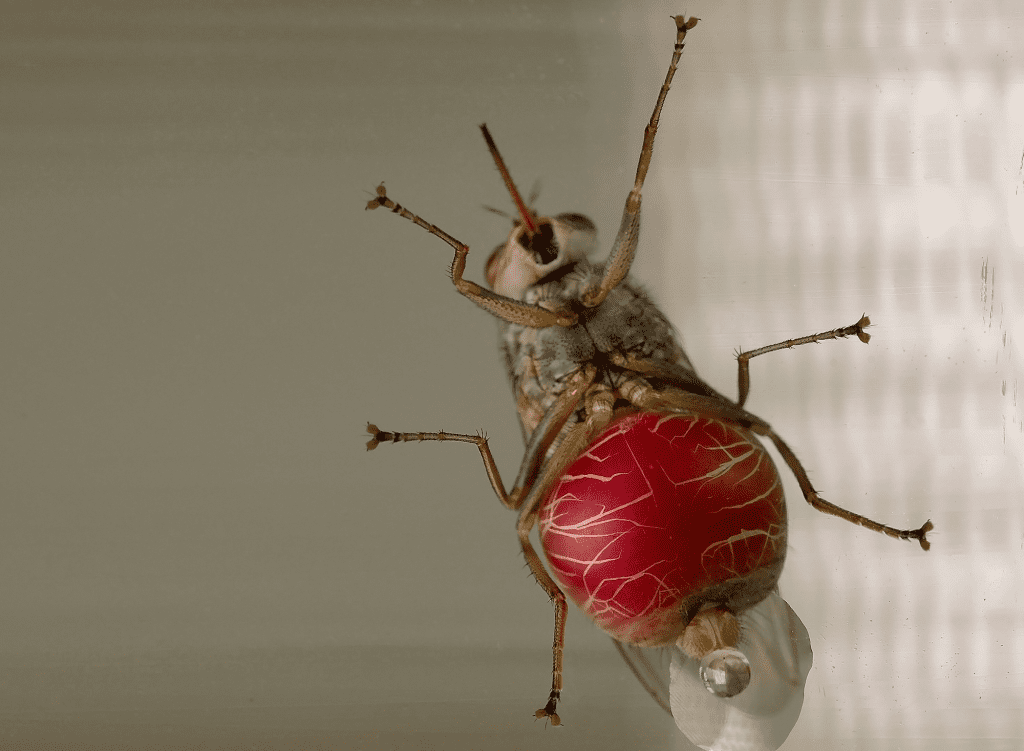

Across most of the animal kingdom, offspring are born smaller than their parents. Astonishingly, several families of insects, including tsetse flies, break this simple rule, and mothers produce offspring their own size or even larger.

An international team from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the universities of Bristol, Greenwich, Stellenbosch and California Riverside, have published an essay in BioEssays that describes this extreme reproductive strategy in tsetse flies, how it might have evolved, and what it means for controlling this disease-transmitting insect.

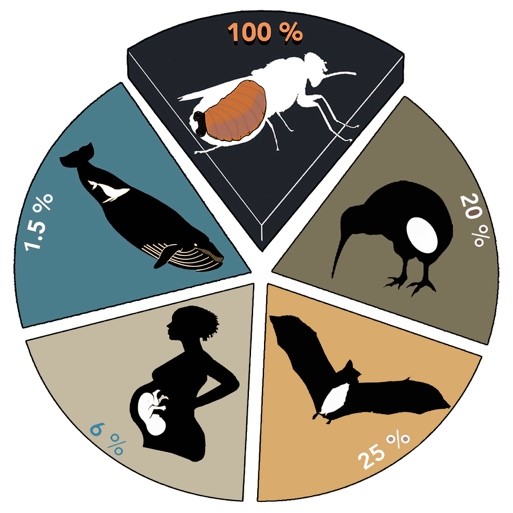

It is difficult to fathom a female giving birth to a single offspring that weighs more than she does. Since we are familiar with human babies, which weigh approximately 6% of the mother’s pre-pregnancy weight, this feat is unthinkable. Even a blue whale calf, the largest baby in the world, weighing an impressive 2700 kg at birth, is only 1.5% of the mother’s weight.

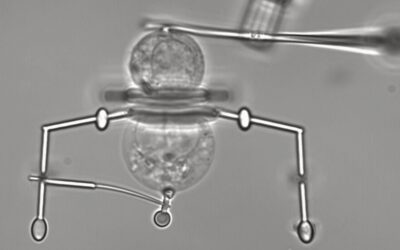

Now, imagine giving birth to a massive baby every ten days for the rest of your life! Unlike most insects, which are egg-layers, female tsetse flies give birth to only one baby at a time. This results in a slow life history in which the females must be continually pregnant and long-lived to produce sufficient offspring to sustain the species. This type of tremendous maternal investment makes one wonder how natural selection could favor this highly implausible trait.

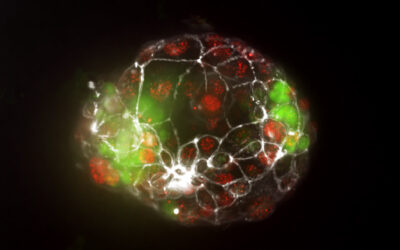

For tsetse flies, producing enormous offspring is possible thanks to two main factors. First, tsetse have a diet consisting exclusively of protein-rich blood, and they can consume over twice their body weight in blood every few days. This allows the female to produce vast quantities of a highly nutritious, milk-like substance to feed a rapidly growing larva. Second, tsetse do not possess the physiological constraints of mammals, such as the pelvic girdle, which prevent birthing of large babies.

Understanding this strange reproductive strategy can help scientists reduce fly populations and control the diseases tsetse flies transmit. Since tsetse larvae remain protected within their mother’s uterus and the pupae are hidden in the soil, controlling tsetse populations is restricted to targeting only adult flies. This contrasts strongly with controlling egg-laying insects, like mosquitoes, where all stages of insect development are susceptible to insect control campaigns. For tsetse, the slow breeding cycle means that you only need to kill a few percent of the adult female flies per day to eradicate a population.

Currently, insecticide applied to cattle and artificial host-like baits, such as “tiny targets” are used successfully to control tsetse populations in disease-endemic areas, such as Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These small, easily deployable and low-cost insecticide-impregnated targets kill both male and female adult tsetse upon contact. Other tsetse control strategies, like releasing sterile males or manipulating the fly microbiome, can be more challenging to implement as large numbers of tsetse must first be reared prior to treatment (irradiation or genetic modification of symbiotic bacteria) followed by field release.

Tsetse populations must, undeniably, be controlled to prevent disease transmission. However, they should also be recognized as biologically fascinating creatures in their own right as they contribute to biodiversity and species richness in tsetse-endemic regions. In areas where human and animal health are not threatened, the preservation of these flies will give us insight into the evolution of pregnancy and motherhood.

Using tsetse flies as a model organism to study pregnancy, we can investigate how environmental changes and stress affect the mothers’ ability to produce high quality offspring. In an analogous situation, if a human mother is malnourished, her baby may not be born strong enough to fight off infectious diseases.

Tsetse flies are a captivating species to study for many reasons beyond their unique reproduction. In the words of Professor Glyn Vale, OBE, who has dedicated his life to the control and eradication of tsetse fly populations in many countries across the African continent:

“I went to Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) as a young man wanting to walk with lions and elephants, but I got ambushed by a tsetse fly who reckoned it could give me more fun and a better chance to be useful. It taught me that its distinctive feeding habits have seemingly inevitable chains of consequences that interweave and reach far — going through matters such as the amazing reproductive system of the flies, their geographical limits, and their impact on human and animal health.

“All of these biological issues ensured that eventually the trail led into lively debates over the appropriateness of widely differing technologies and strategies for control. Thus, the tsetse that I first met 55 years ago has kept its promise to give me, in its own way, exactly what I was really after: a varied, adventurous, and challenging walk on the wild side.”

Check out the video “Burrowing for knowledge” for more background about the project, led by Dr. Sinead English at the University of Bristol and funded by the BBSRC and Royal Society

Reference: Lee R. Haines, et al. Big Baby, Little Mother: Tsetse Flies Are Exceptions to the Juvenile Small Size Principle. BioEssays (2020). DOI: 10.1002/bies.202000049