Cooling devices are considered to be power guzzlers, in which polluting refrigerants are still used, even after the ban on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). An environmentally friendly alternative are systems which use water instead. A research team at the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at Kiel University, together with the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE in Freiburg, has developed a highly-porous material, with which these cooling systems can be operated using less electrical energy than before. Previously-unused waste heat could be used for that., e.g. from data centers.

Data centers are real energy factories: as a side-effect of their operations, high-performance computers produce a lot of heat, and must therefore be cooled continuously. As such, they cause high energy and power costs, while giving off unused waste heat to the environment at the same time – its temperature is too low for other uses. Theoretically, however, this could be used for running energy-efficient cooling systems, which use water as a refrigerant. To do so, the material used there must be able to absorb a lot of water and regenerate at the lowest possible temperatures.

The porous material, developed by Professor Norbert Stock from the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry and his working group, fulfils these requirements. This way parts of the cooling process of adsorption-driven chillers can be operated using only the energy from existing waste heat or solar thermal systems. “This could also make an important contribution to the use of renewable energies,” said Stock. For environmentally friendly systems like this the material has two key advantages: “The systems consume less power, and we can produce the material in an eco-friendly manner,” explained the chemist.

In these so-called adsorption-driven chillers, the cooling effect occurs when ambient heat is extracted by the evaporation of water. The molecules of water vapour are deposited in the cavities of a porous material, called sorbents, i.e. adsorbed by it. In the following regenerative phase the material is dried by applying thermal energy. The stored water molecules are released, liquefy and can be evaporated again in the next cycle. The material can also be used again.

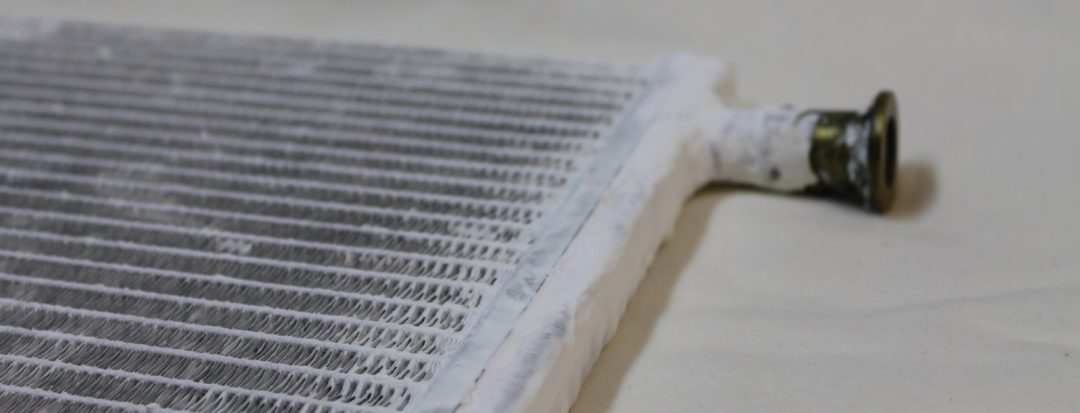

The Kiel working group has already been pursuing the discovery for a long time – but previously only as pure fundamental research. For transfer to an industrial application, they worked with colleagues from the Fraunhofer ISE to coat commercially available heat exchangers with their material. “The survey of the heat exchanger under application-related conditions shows the high potential of the material” said Dr Stefan Henninger from the ISE. In the laboratory, the material can already be produced in kilogramme quantities. “In order to produce the material for an industrial use on a larger scale, our next step is to contact other companies,” said Stock. They have already applied for a patent for their production method.

Photo: Dirk Lenzen